Suburban Legend

By David Baddiel

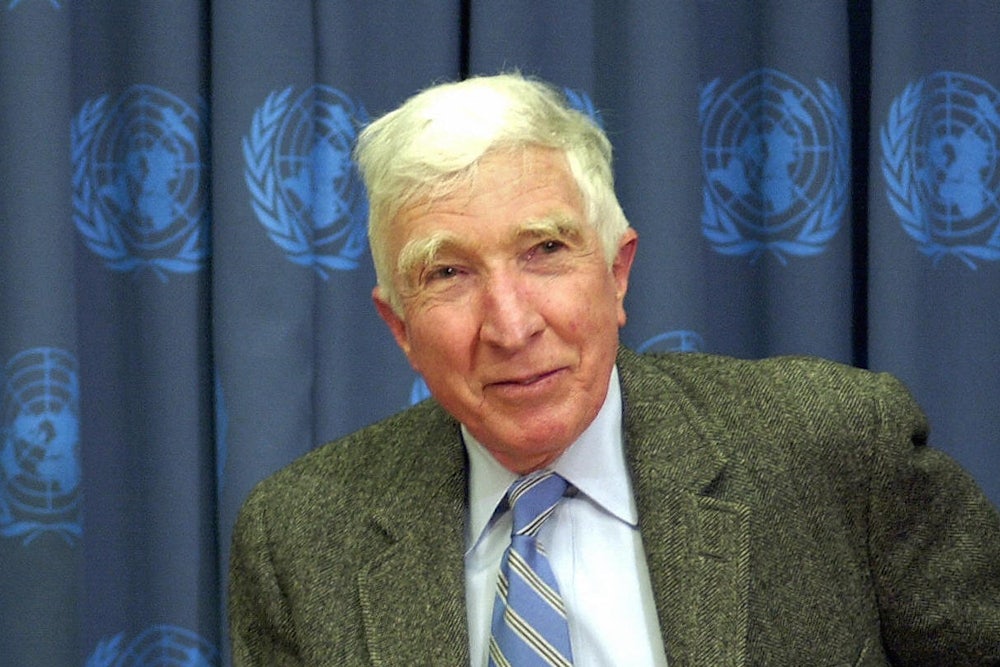

Let’s begin by making one thing clear. John Updike was the greatest writer in English of the last century. Unquestionably, he was the best short story writer; I would argue the best novelist, certainly of the postwar years; one of the very best essayists and in the top 20 poets. Adding up the extraordinary breadth of his work – although Updike’s profligacy has always been counted against him, implying a troubling ease to his oeuvre that sits uneasily with our expectation of genius —his position at, or near, the top of the modern canon should be undeniable.

But Updike has always had detractors, beginning, in 1965, with John W Aldridge (no relation, I believe, to the striker who did so well for Liverpool after his lookalike Ian Rush had left), a professor of literature at Michigan University, who remarked, reviewing Of the Farm in the New York Herald Tribune, that though he “does on occasion write well ... Mr Updike has nothing to say”. Versions of this sniffy claim that he was a writer of inconsequence dogged Updike’s reputation throughout his career. Harold Bloom pompously called him “a minor novelist with a major style” and James Wood even more pompously wrote: “Updike is not, I think, a great novelist.”

The issue of Updike’s greatness hangs over this new biography by Adam Begley, who tries in his introduction to dismiss any anxiety that the subject of this long, insightful and meticulously researched book may be a second-rank talent by asserting: “Predicting his eventual place in the pantheon of American literature is ... no more useful than playing pin-the-tail with the genius label.” This anxiety, though, reflects a fairly consistent category error in American critical circles. Updike’s central creative project—like that of Jane Austen, George Eliot or Joyce but, I would contend, more extremely, perhaps more artfully, even than any of those—is, in his own phrase, to “give the mundane its beautiful due”.

He is the great poet of the ordinary life, of domesticity, of life as most people live it—as opposed to Saul Bellow, who writes mainly about life as deep-thinking intellectuals, academics and writers live it (and who was considered, mistakenly, a better writer throughout that time when the “Great Male Narcissists,” in David Foster Wallace’s phrase, ruled the literary cosmos). The problem for gravitas-chasing critics such as Bloom and Wood was that Updike writes small – and they mistook this for the size of his talent.

“Small” doesn’t really do him justice. A better word would be “microscopic”: using the microscope of his extraordinary prose, Updike reveals and articulates the largest mysteries of life. And a fan—you may have gathered I am one – cannot complain about the microscopic quality of Updike. A vast amount of minutiae about the writer’s life is in there and I devoured it all. That his first wife, Mary, tearfully insisted that their first child be born in hospital despite the 1950s NHS policy (they were living in Oxford at the time) of promoting home births; that Updike at Harvard queued for so long to see T S Eliot that he fell asleep during the reading; that a 300-year-old beam held up his first family house in Ipswich, Massachusetts – these and many other small informational vignettes pepper Begley’s pages. I would suggest that Updike, the master of detail, would have appreciated it all.

I devour it not just as a fanboy but also as a reader and critic of Updike. It is Begley’s contention that virtually all of Updike’s fiction is in some way autobiographical and a fair amount of this biography is exegesis, uncovering how real events in the writer’s life played into his novels and short stories.

Some of this would be immediately apparent to anyone who knows his work well. Thus, reading about how Updike used to organise touch football every Sunday for the couples in his social set in Ipswich illuminates and reinforces the reality of a passage that I have always loved, this stunning lyrical epiphany on what it means for adults to be playing and then ending games, from Couples:

She was to experience this sadness many times, this chronic sadness of late Sunday afternoon, when the couples had exhausted their game ... and saw an evening weighing upon them, an evening without a game, an evening spent among flickering lamps and cranky children and leftover food and the nagging half-read newspaper with its weary portents and atrocities, an evening when marriages closed in upon themselves like flowers from which the sun is withdrawn, an evening giving like a smeared window on Monday and the long week when they must perform again their impersonations of working men, of stockbrokers and dentists and engineers, of mothers and housekeepers, of adults who are not the world’s guests but its hosts.

This is self-evidently beautiful writing. It is also far from inconsequential. It’s an inconsequential situation, of course, one that we all have had at some point – of depressively realising that a Sunday afternoon of socialising and sport is drawing to a close and soon it will be the working week again—but it uses that small experience to tell a large truth about humanity, which is that adults are all, to a greater or lesser extent, simply grown-up children, simply playing at being adults, and our games, whether it be touch football or infidelity, are just a way of deferring the future and all

the loss it entails.

Some of the links that Begley draws between Updike’s life and the fiction, however, would not have been available to even his most avid reader without the information presented here. For example, it is a moot point how his fiction, drawing as it does heavily on his life and being regularly centred around the “sad magic” of suburban adultery, must have gone down at home. In a television documentary, his son David said that for his father writing took “precedence over his relations with real people” and the assumption is that Updike was so committed to his fiction that he was always prepared to publish and be damned.

So it is a surprise to discover that he held back certain stories, even novels, for years—Marry Me, his most dissecting exploration of a crumbling marriage, was written in the mid-1960s but stowed away in a safe deposit box at the First National Bank of Ipswich for 12 years, in order to avoid causing hurt to his first wife, Mary.

As well as being an intricate portrayal of the man, Updike is also a sustained, very fine work of literary criticism. It is particularly good on Updike’s artistic amorality. By “amorality,” I don’t mean that there are no moral principles underlying his work but that there is—as regards the behaviour of his main characters— an absence of blame. There is a problem with the way people read novels now, most obvious in Amazon reviews, in which readers consistently confuse whether or not a novel is good with whether or not they “like” the characters. Generally, readers imagine that if they don’t like the characters in a novel, it is a bad book.

To make matters worse, whether or not they like the characters is usually based on whether or not the characters behave nicely. All of this is a disaster for literature and particularly for Updike, whose characters never behavenicely or, indeed, evilly—they just behave like people do, in a flawed way. “People are incorrigibly themselves” was his motto in creating his people.

In a lecture that Adam Begley quotes, Updike defines his “aesthetic and moral aim” as “non-judgemental immersion” and he followed this throughout his career, achieving its apotheosis most completely in the character of Harry Angstrom in the Rabbit series. No religious writer (he was a practising Christian all his life, and Updike’s infusion of smallness with significance is generated by a sense of seeing everywhere—in a pigeon feather, in a golf swing, in sex—the divine) has ever been so non-judgemental.

Begley, however, cannot resist occasionally judging the man, particularly in that realm where Updike the writer is the least judgemental: the sexual. He describes Updike’s comment, in an interview with a feminist journalist, that “to be unmonogamous is a great energy consumer” (surely true?) as an “ill-considered quote”; he suggests that the “enthusiasm” with which Updike “threw himself ... into the tangle of Ipswich infidelities” was “reckless”; and he writes, “A hyperactive libido is a component of his character that can’t be ignored” (but why might we need it to be?).

Updike’s description in his memoirs of himself flirting with a “pretty housewife” while playing volleyball is called by Begley “preening”, which isn’t at all wrong but ignores that the writing is, as always, acutely self-aware, beginning: “What concupiscent vanity it used to be . . .”

Perhaps this is just the nature of biography, that some judgement has to be made, some record of what you, the biographer, feel about the moral condition of your subject. (Plus I note that, in an afterword, Begley profusely thanks Mary, Updike’s first wife, for her time—not Martha, his second, whose character, both in reality and in versions of her in her husband’s later fiction, is presented very firmly as that of a naysayer. I wonder if his feelings about Updike’s relationships with other women during the 1960s became a little defensive on Mary’s behalf.)

But it brings into relief how little Updike judged. He just lets his characters – and their damaging conflicts between duty and desire—stand. As William Maxwell, his editor for many years at the New Yorker, once wrote (in a letter comforting him following another critical accusation of shallowness), his fiction is always “concentrated reflection”: the mirror is never skewed by morality.

This, I think, is another reason why Updike has so many detractors. Ever since F.R. Leavis wrote The Great Tradition, there has been a school of literary criticism that has demanded that great novelists also be great moralists: that the job of the writer is not just to reflect the world but to tell it the difference between right and wrong.

That is a mistake. A good writer leaves that decision to the reader; a great writer challenges our preconceptions of right and wrong by forcing us to engage and sympathise with characters who confound those preconceptions. The job of the artist is not to pardon or pass sentence upon the world but simply – or not simply, for this is the difficult thing—to show it and its most complex and most difficult truths.

Updike’s lodestar for the novel was, as Begley points out, Stendhal’s contention: “A novel is a mirror carried along a high road. At one moment it reflects to your vision the azure skies, at another the mire of the puddles at your feet.” Updike wrote in the way he did because his mirror was extremely bright and his road was very long—it was America and the world beyond. He wrote in the way he did, in other words, not because he had nothing to say but because he had everything to say.

David Baddiel’s novels include The Death of Eli Gold.

A Narcissist with a Thesaurus

By Jeffrey Meyers

The outpourings of John Updike—who contributed 146 made-to-order stories and innumerable poems, reviews and Talk of the Town comments to what he called, echoing Voltaire’s Candide, “the best of all possible magazines”—exemplify all the faults of the New Yorker. With sustained mutual admiration, Updike and most other contributors glorified what Adam Begley (joining the forced hallelujahs) calls the magazine’s “awesome,” “legendary” and “Olympian figures”: the first editor, Harold Ross, a crude bore; his anointed successor, William Shawn, a faceless dullard; and the editor Katharine White, a prissy fusspot.

Elizabeth Bishop rejected her editor’s patronising pronouncement, “We avoid printing anything that might confuse or puzzle our readers,” and complained about the genteel tone that made all New Yorker poetry sound “just alike and so boring”. The intrusive editors quarrelled over a semicolon but encouraged facile content and ironed out all traces of distinctive style.

The slick surface of the magazine’s robotic prose (pieces would open with a formulation such as: “On November 14 1953 at 3.57pm on 55th Street . . .”) disguised the meretricious glamour that pandered to snobbery and greed and the shallow sophistication that masked suburban values. Many writers in the New Yorker (including Updike, in his book and art reviews) specialised in pretentiously recycling familiar material, cunningly packaged to make it seem new.

Updike (of Dutch ancestry and originally Opdyck) grew up in Shillington, near Reading, in eastern Pennsylvania. His father was a high-school maths teacher, his mother a published but unsuccessful writer. Updike made a smooth transition from small-town and sometimes rural life to Harvard, the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in Oxford and his beloved New Yorker, but he was not accepted by Princeton or by Archibald MacLeish’s writing class at Harvard.

As a boy and a man, Updike was weird-looking. He had a long, narrow face, a huge raptor’s beak, owlish spectacles, a shock of unruly hair and a high, braying laugh – topped off by scaly psoriasis and a debilitating stutter. Yet Begley notes that unlike most modern writers Updike had no tormenting inner demons: “He wasn’t despairing or thwarted or resentful; he wasn’t alienated or conflicted or drunk; he quarrelled with no one.” Philip Roth, upset by Updike’s negative review of Operation Shylock, was one exception.

The astonishingly fluent Updike wrote three or more pages every morning with tremendous concentration and efficiency. It’s hard to believe, Begley writes, “that someone as prolific as Updike, who guided his writing through the editing and production process with such meticulous care and without the assistance of an agent; who read voraciously, as though cramming constantly for a final exam in universal knowledge; who carried on a voluminous correspondence with a wide array of professional colleagues, played golf [with an unimpressive 18 handicap] twice a week, volunteered for numerous civic duties, and enjoyed an agitated social and romantic life”, also found time for the welcome distractions of gardening and household repairs. But Updike’s prose sometimes seemed as if it had been written on a typewriter by a typewriter.

He married his first wife, Mary Pennington, the daughter of a Unitarian minister and graduate of Radcliffe College, in 1953 and had four children with her. Both he and Mary had many lovers; their marriage foundered on infidelity and he married his second wife, Martha Bernhard, in 1977. He lived first in Manhattan while working for the New Yorker, then in Ipswich with Mary and in Beverly with Martha – both towns north of Boston. He also changed denominations as he changed towns and wives and lovers and moved from the Lutheran to the Congregational to the Episcopal Church.

Seizing the prerogative of the successful writer, Updike – in his own words, “a stag of sorts in our herd of housewife-does” – had sexual adventures with his eager admirers. His suburban adultery, endlessly recounted in his novels, seemed shocking in the 1960s but now seems tediously passé. He was all too willing to be cuckolded if he was free to fornicate. A local sexual scandal after his first serious affair provoked a reparative trip to Europe with his wife and to a surprisingly depressing villa in Antibes.

Defending Lyndon Johnson’s military manoeuvres, Updike supported the war in Vietnam. Though he opposed the prevailing liberal view, he was rewarded by the literary establishment and enjoyed tremendous success as the “accolades, prizes, honours, and riches piled up in rapid succession”. He went on a US State Department-sponsored tour of Russia and eastern Europe and, unwilling to refuse any invitation, indulged in a worldwide travelling frenzy during the last four decades of his life. He earned $70,000 in 1967; the following year, his novel Couples, which made him famous and notorious, earned $360,000 for film rights and $1m in royalties. Though few people knew he was ill, he died of lung cancer in January 2009.

Begley’s biography is competent and readable but he is besotted by his subject. His book is weighed down (sometimes sunk) by an excessive amount of literary criticism and by protracted discussions of no fewer than 136 mediocre and transparently autobiographical stories and articles. He solemnly quotes Updike’s pronouncement, “I disavow any essential connection between my life and whatever I write,” and asserts: “It’s a mistake to casually conflate character and author.” Yet, throughout his book, he first describes the events in Updike’s life, then mechanically recounts the fictional repetition of these incidents. Hemingway, an early influence, constantly sought new experiences to write about. Updike, cherishing every scrap of his personal life and striving for mythical significance in his daily doings, fell back on the trivial and tedious details of his small-town childhood.

Begley calls Updike “America’s pre-eminent man of letters”, “a great American writer” and “the best novelist-critic of his day”. He praises his “monumental erudition”, though Updike confessed that he “never liked intellectuals” and admitted, “I can read anything in English and muster up an opinion about it.” However, the evidence that Begley adduces for the greatness of his hero does not substantiate his inflated claims. Updike’s New Yorker reviews of literature and art were high-grade book reports with very little penetrating analysis, designed to be easily digested by his middlebrow readers. Mary McCarthy and Gore Vidal were more perceptive and amusing critics and, compared to Edmund Wilson and George Steiner, Updike was a dwarf among giants.

While writing poetry, Updike, like Molière’s M Jourdain, made prose all thetime without knowing it. Two plodding examples, quoted by Begley, prove the point: “You stay as unaccountable/as the underwear left to soak/in the bowl where I brush my teeth”; and with forced emotion on the occasion of his mother’s death, “ ‘O Mama,’ I said aloud, though I never called/her ‘Mama’, ‘I didn’t take very good care of you.’ ”

Begley dismisses Updike’s critics as slippery and spiteful but has no real answer to them. John W Aldridge, in a savage review in 1965 that wounded Updike, argued that he lacks emotional content and has nothing to say: “He does not have an interesting mind. He does not possess remarkable narrative gifts or a distinguished style. He does not create dynamic or colourful or deeply meaningful characters.” Christopher Hitchens’s review of Terrorist, a novel inspired by the events of 11 September 2001, exclaimed: “Updike has produced one of the worst pieces of writing from any grown-up source since the events he so unwisely tried to draw upon.”

Updike’s long career combined the blandness of the tranquillised 1950s with the narcissism of the Me Generation. In a brilliant, hilarious review in 1998, David Foster Wallace said that Updike’s principal character Rabbit Angstrom is “symptomatic of the prison of self-absorption and egoism that afflicted so many Americans”. He memorably called Updike “just a penis with a thesaurus” and, referring to his enormous output, asked, “Has the son of a bitch ever had one unpublished thought?”

Updike’s novels are not nearly as good as those of Saul Bellow and Vladimir Nabokov and his tame non-fiction does not match the coruscating essays of Norman Mailer and James Baldwin. In the end, for all his cataract of words, Updike not only failed to transcend the superficial and vacuous New Yorkervalues but also came to embody them.

Jeffrey Meyers, a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, is the author of Thomas Mann’s Artist-Heroes. His next book, The Heedless Heart: Robert Lowell and Women, will appear next year.

This piece first appeared on newstatesman.com.