The Embrace of Unreason: France, 1914-1940 by Frederick Brown (Knopf)

Dancing with the devil is an old pursuit among French writers. Even such a stalwart of the Enlightenment as Diderot created a fictional character (the seductive Nephew of Rameau) who could remark, “If there is any genre in which it matters to be sublime, it is evil, above all.” From Diderot through de Sade and de Maistre, Baudelaire and Huysmans, down to Michel Houellebecq and Jonathan Littell, a powerful tradition within French writing has challenged the bounds of conventional morality, loudly defied the dictates of Enlightenment reason, and expressed an abiding fascination with blood. It is as if the culture that, perhaps more strongly than any other, celebrated reason and geometrical order, also provoked within itself a deep, wild, and willfully primitive reaction, a return of the repressed par excellence.

Never in French history did this cultural impulse prove more pernicious than during the troubled decades of the Third Republic (1870–1940). In this period, some of France’s most talented writers gazed longingly into the abyss, and then turned the full power of their eloquence against the institutions of parliamentary democracy. Even as the frail Republic lurched from scandal to scandal and crisis to crisis, writers on both the left and the right subjected it to endless, pitiless mockery and abuse. Robert Brasillach, one of the most brilliant writers and critics of his generation, likened it to “a syphilitic old whore, stinking of patchouli and yeast infection.” Charles Maurras, an enormously skilled polemicist, endlessly denounced it as “the Jew State, the Masonic State, the immigrant State.” Such attacks did much to drain French democracy of legitimacy precisely at its moment of greatest peril. They made it all too easy for a portion of France’s elites to treat the crushing defeat of 1940 as history’s judgment on a corrupt and senile society, and therefore to embrace Hitler’s grotesque New Order rather than to struggle against it.

Frederick Brown, an accomplished literary biographer, has emerged as the leading English-language chronicler of this appalling but fascinating French story. In his book For the Soul of France, he examined the fin de siècle, with particular attention to what he called the “culture wars” between left and right. He centered his account on the Dreyfus Affair, in which the trumped-up conviction of a Jewish army officer on treason charges unleashed a political firestorm that came close to bringing the Republic down. Now, in The Embrace of Unreason, he has taken the story through the interwar period. This time no single “affair” dominates the landscape, but the specter of Vichy looms on the horizon, as the final destination at which so many of those who “embraced unreason” eventually arrived.

Had Lillian Hellman not already (mis)used the title, Brown might well have called his book Scoundrel Time. The 1920s and 1930s in France were a moment when extreme ideological currents swept unstable, marginal, even criminal figures out of their ordinary recesses into positions of remarkable prominence. One of the worst was a pathologically dishonest drunk and embezzler named Louis Darquier, who styled himself Baron Darquier de Pellepoix and spent most of the 1920s stumbling from one fraudulent scheme to another, half a step ahead of his creditors. Then, in 1934, he took part in a massive riot in which extreme right-wing groups tried to overthrow the French National Assembly, and was shot in the thigh by police. The resulting celebrity catapulted him to the front ranks of the extreme right, and over the next years he established himself as a leading voice of French anti-Semitism, editing a journal called L ’ Antijuif. Brown quotes a representative article: “The element of disintegration, the element of division, the microbe is the JEW.... [We] assert that the solution to the Jewish problem is the prerequisite for any French renovation.” Even as France was finally awakening to the dangers of German rearmament, Darquier was secretly taking money from the Nazis. During the occupation, he became head of Vichy’s General Commission for Jewish Affairs, and helped the Germans to organize the deportation of Jews from French soil. (Seventy-six thousand of them died in the camps.) In 1944, he escaped over the Pyrenees to Franco’s Spain and lived to a ripe old age in Madrid, insisting to the end that only lice had died in Auschwitz.

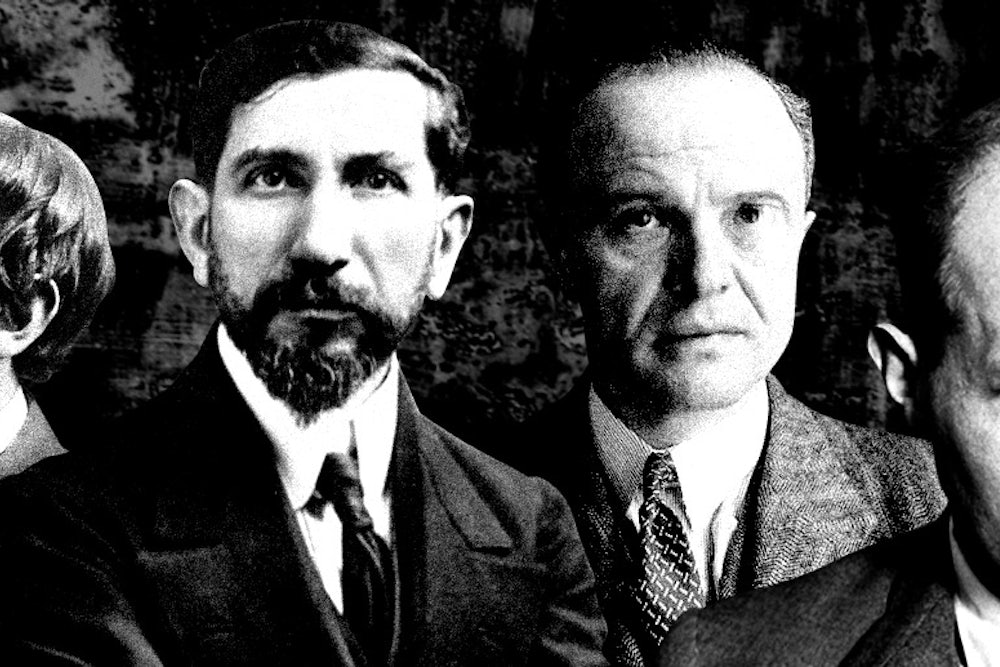

Although Darquier appears in The Embrace of Unreason, Brown reserves his principal attention for writers of real talent—three in particular. Maurice Barrès, who died in 1923, was a wildly popular novelist and anti-Dreyfusard best known for his work The Uprooted, published in 1897. A story of a group of young men from his native province of Lorraine, it excoriated the Republic’s secular educational system for supposedly destroying the connection between French students and their native soil and “race.” Maurras, a hugely prolific poet, critic, and journalist, became the guiding spirit of the reactionary movement known as the Action Française, and lived long enough to spend his last years in prison for “complicity with the enemy” during the Occupation. Upon his conviction in 1945, he exclaimed: “It’s Dreyfus’s revenge!” Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, younger than the others, was a novelist and critic who openly embraced fascism in the 1930s. Rather than face trial as Maurras had done, he committed suicide soon after the liberation.

As in For the Soul of France, Brown tells his story in an episodic, sometimes impressionistic manner. He mixes chapters about Barrès, Maurras, and Drieu together with vignettes about a variety of scandals and causes over which the apostles of “unreason” obsessed. One chapter follows the long campaign to canonize Joan of Arc, which finally came to fruition in 1920. The Action Française celebrated Joan as a symbol of the true Catholic France, and held her up against the godless Revolution of 1789, regularly staging massive processions that ended at Joan’s golden statue in the Place des Pyramides in Paris. (In recent years, the National Front of Jean-Marie Le Pen and his daughter, Marine, have continued the tradition.) Barrès, Maurras, and Drieu all had a near-fatal weakness for neo-Romantic medieval kitsch. Another chapter delves into the Stavisky Affair of 1934, which centered on the collapse of a massive Ponzi scheme perpetrated by a Russian-born Jew named Alexandre Stavisky. Thanks to his close connection with government ministers, the affair led to the collapse of the ruling center-left coalition, and prompted the rioting in which Louis Darquier was shot. Yet another vignette traces the hilarious far-right obsession with Maggi, a staid Swiss dehydrated-food manufacturer (still in business and now part of Nestlé), which the Action Française accused of cloaking a vast “Jewish-German” espionage network.

Occasionally Brown’s method becomes needlessly distracting. He repeats information, jumps back and forth in time, and returns to themes and characters already discussed in his earlier book—indeed, despite the dates in the subtitle, much of this book’s first hundred pages returns to the fin de siècle. Brown never provides an overview of the period’s history, and uninitiated readers will find themselves having to flick back continually to a timeline that he provides at the end. Despite some fine pages on Surrealism, he does disappointingly little with the visual arts, and largely neglects some writers who would have fit naturally into his story, such as Robert Brasillach and perhaps Céline. Still, the book as a whole is more than engaging enough to assuage these irritations.

Although Brown’s principal fascination lies with the far right, he does not ignore the other side of the political spectrum, which offered its own brand of unreason during these years. The Communist poet Louis Aragon weaves in and out of the narrative, and so, more substantially, does the Surrealist poet and artist André Breton, who joined the Party in 1927 but could never match Aragon’s orthodoxy (leading to his expulsion in 1933). In an atmosphere where the political extremes often touched, both men were for years close friends with Drieu La Rochelle. Brown also has a memorable description of the Paris Exposition of 1937, in which the twin ideological threats to the Republic took on alarmingly physical form. On one side of the Eiffel Tower the Soviets constructed a stone monolith topped by twin heroic figures, each seventy-five feet tall, “thrusting the hammer and sickle skyward like conquistadors setting foot on a new continent.” On the other side, Hitler’s architect Albert Speer answered with an even taller monument, topped by a twenty-foot tall Germanic eagle, “its wings spread like Dracula’s mantle.”

Brown also has space for at least a couple of heroes, familiar enough to adepts of French history, but presented here with verve. Even as the French were preparing, in 1914, to march off to a war that Maurice Barrès would celebrate as “a resurrection,” at least one French politician had the courage to dissent. “Today you are told: act, always act!” the Socialist Jean Jaurès declared in January 1914. “But what is action without thought? It is the barbarism born of inertia.... [T]o stand for peace today is to wage the most heroic of battles.” Six months later, just three days before France declared war on Germany, Jaurès was shot and killed by a nationalist hooligan, who was later acquitted by a pro-war jury.

Brown also introduces one of Jaurès’s disciples, Léon Blum, a talented writer and politician whose early admiration for Maurice Barrès did not survive the Dreyfus Affair. In 1936 Blum, now leader of the French Socialists, barely escaped Jaurès’s fate when a gang of Action Française thugs dragged him out of his car on the Boulevard Saint-Germain and beat him savagely. He survived, led the Popular Front to victory in that year’s parliamentary elections, and became France’s first Jewish prime minister, whereupon the deputy Xavier Vallat greeted him with a notorious speech in the National Assembly: “Your assumption of power, Mr. Prime Minister, is unquestionably an historic event. For the first time, this old Gallo-Roman land will be governed by a Jew.... I say what I think—and bear the disagreeable burden of saying aloud what others only think—which is that this peasant nation would be better served by someone whose origins, however modest, reach into the entrails of our soil than by a subtle Talmudist.” Vallat, a close friend of Charles Maurras, would go on to precede Louis Darquier as the first head of Vichy’s General Commission for Jewish Affairs.

The really remarkable sections of Brown’s book, however, are not the ones that deal with politicians or scandals, but with the three writers Barrès, Maurras, and Drieu. And even here, one subject in particular stands out. The portraits of Barrès and Maurras are nuanced and sensitive, but both men, despite their talent, moved too easily and quickly from serious spiritual struggle to glib, simple partisanship to be truly interesting. Indeed, both often put their talent aside entirely in the service of partisan hackery. Maurras, who went almost entirely deaf at age fourteen, certainly had pathos in his life. But his massive output all too often consisted of nothing more than wittily vulgar abuse, littered with all manner of racial and anti-Semitic slurs.

Drieu La Rochelle, although he, too, ultimately failed to become a truly great writer, was different. At age 15, in 1908, the mischievous, antic adolescent had a fateful encounter with Nietzsche. Thus Spake Zarathustra enthralled him, and he went on, in his penultimate year of school, to tear through Descartes, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Schelling, Fichte, Bergson, Hartmann, William James, Darwin, and Spencer. In 1914, he went off to fight in World War I with a copy of Thus Spake Zarathustra in his knapsack. The war only confirmed the lessons he found in Nietzsche about vital energy and the dangers of degeneration. “The trump of war sounded in my blood,” he wrote later. “At that moment, I belonged body and soul to my race charging through the centuries ... toward the eternal idol of Power, of Grandeur.”

After the war Drieu joined an eclectic and politically ecumenical literary circle that included the three great Andrés of interwar literary France: Breton, Malraux, and Gide. To Breton, in 1927, he dedicated a memoir called The Young European, arguing that parliamentary democracy had driven France to decadence. As Brown points out, Breton’s Surrealism, with its longing for some new creation, born out of the unconscious and capable of recovering a forgotten human unity, was all too compatible with the post-Romantic sensibility that had also nourished Barrès and Maurras. “With its penchant for the bizarre and the surprising, its contempt for bourgeois morality, its black humor, its glorification of evil genius, its language of rebirth, its messianism, its explorations of the erotic at the margin of death, the postwar literary generation envisaged a new human condition and succumbed to the ravages of a twentieth-century mal de siècle.”

Drieu himself wrote some works of considerable power. His short novel Le feu follet (“The Manic Fire”), from 1931, although tinged with hackneyed criticisms of European degeneration, gave a darkly disturbing picture of a heroin addict’s descent into despair, and his ultimate suicide. Drieu’s criticism could be acute, and he deserves much of the credit for bringing Jorge Luis Borges to European attention after a trip he made to Argentina in 1933. “My poet walked and walked, striding like one possessed,” Drieu recalled of the time he spent with Borges. “He walked me through his despair and his love, for he loved this desolation.”

But in the end Drieu’s politics overwhelmed and crushed his literary inclinations. In January 1934, he spent a week in Nazi Berlin, and was enraptured. A month later, he witnessed the Paris riots in which Louis Darquier was wounded, and cheered on the forces trying to overthrow the Republic. In 1936, he attended the inaugural meeting of the Parti Populaire Français, a fascist party led by a thug-like former Communist named Jacques Doriot. Drieu fantasized that Doriot was the messianic leader who could break through the pettiness, the banality, and the ordinary corruptions of life and recreate “great communions.” Drieu thenceforth styled himself the poet of fascism, defending it as “the political movement that charts its course most straightforwardly, most radically toward a great revolution of mores, toward the restoration of the body—health, dignity, plenitude, heroism.” His writing turned steadily more crude, and he gave vent to gutter anti-Semitism. “In whatever language decadence slavers,” he wrote in an inferior novel called Gilles, “whether it be Marxism or Freudianism, the words of Jews inform the drool.” The novel portrayed a France undermined by the assimilation of all manner of “alien” elements, including Jews, feminists, homosexuals, and Surrealists (a movement with which Drieu had by this time definitively broken).

Drieu was now prepared for his role as a leading impresario of cultural collaboration. During the occupation, he feverishly supported Marshal Pétain’s “National Revolution,” and took over the most important French literary periodical, the Nouvelle revue française. The fact that he used his influence to save some friends from the Nazis (including a former wife who had been born Jewish) cannot mitigate this record, and to the end Drieu remained loyal to a horrific ideal. “I hope for the triumph of totalitarian man over the world,” he confided to his journal in June 1944. “Enough of this dust of individuals in the crowd.”

Drieu La Rochelle’s darkly fascinating career inspires Frederick Brown to some remarkably fine writing. “Despair was Drieu’s homeland,” Brown writes of the young author. “The character Drieu could flesh out most convincingly was his shadow.” By the time Drieu gave himself over fully to fascism, Brown comments, he “felt alive only within the radiant circle of a hero.” Brown brilliantly calls Gilles “a picaresque novel with the bones of a thesis regularly poking through the flesh of its characters.” All in all, these pages of Brown’s book provide one of the most acute portraits I have read of how a writer succumbs to the lure of political fanaticism. They stand with Carmen Callil’s brilliant biography of Louis Darquier as among the most lucid examinations of this chapter in the history of European darkness.

Although Brown finishes the book with a nine-page epilogue on Drieu’s role in the occupation, The Embrace of Unreason, properly speaking, comes to an end in 1940. Will Brown now continue his multi-volume investigation of French unreason with a third book, on Vichy? If so, he will enter into some heavily trodden scholarly territory, and the sheer weight of events may prove hard to convey in his loose, impressionistic style. Still, it would be wonderful to see him try. The French, under Vichy, had more freedom than most Europeans under Nazi rule to choose among the paths of collaboration, resistance, or apathy, making the country’s wartime experiences a moral drama of the first order. There are few writers better positioned to explore this drama, and the way that so many of the brightest minds in France failed the test—not only gazing into the abyss but plunging willingly over the edge.