In the newest issue of The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates makes the case for slavery reparations. “The idea of reparations is frightening not simply because we might lack the ability to pay,” Coates writes. “The idea of reparations threatens something much deeper—America’s heritage, history, and standing in the world.” The piece is provocative, but short on details: It doesn't put a number to what black Americans are owed, and it doesn't provide a specific prescription for how to make reparations. Rather, Coates simply recommends that Congress pass Representative John Conyers’s bill for a “Congressional study of slavery.”

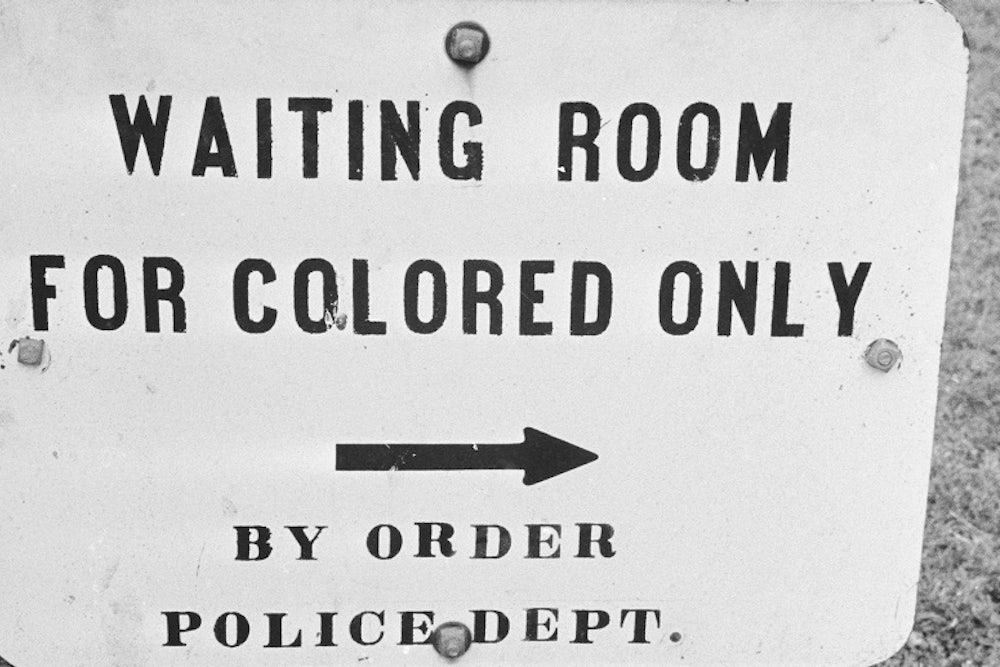

But now that Coates has re-ignited this debate, it's worth considering the practical implications. How much money, for instance, is due to black America? How should that money be distributed? Who should be eligible for it? Perhaps those are questions that a Congressional study could answer. What academic evidence we have provides an incomplete but sobering assessment of the costs of centuries of slavery, Jim Crow, and state-sanctioned discrimination.

How much should reparations be?

As Coates explains in his piece, reparations must compensate African Americans for more than just the centuries of slavery in the United States. After slavery was abolished, whites frequently lynched black Americans and seized their property. A 2001 Associated Press investigation, which Coates cites, found 406 cases where black landowners had their farms seized in the early-to-mid 20th century—more than 24,000 acres of land were stolen. Housing discrimination, which has been one of the largest obstacles to African Americans' building wealth, still exists today.

Larry Neal, an economist at the University of Illinois, calculated the difference between the wages that slaves would have received from 1620 to 1840, minus estimated maintenance costs spent by slave owners, and reached a total of $1.4 trillion in 1983 dollars. At an annual rate of interest of 5 percent, that’s more than $6.5 trillion in 2014—just in lost wages. In a separate estimate in 1983, James Marketti calculated it at $2.1 trillion, equal to $10 trillion today. In 1989, economists Bernadette Chachere and Gerald Udinsky estimated that labor market discrimination between 1929 and 1969 cost black Americans $1.6 trillion.

These estimates don’t include the physical harms of slavery, lost educational and wealth-building opportunities, or the cost of the discrimination that persists today. But it’s clear the magnitude of reparations would be in the trillions of dollars. For perspective, the federal government last year spent $3.5 trillion and GDP was $16.6 trillion.

What form should reparations take?

In a 2005 article, economists William A. Darity Jr. and Dania Frank proposed five different ways to make reparations. The first approach is lump-sum payments. This is the most direct form of reparations, but it does not correct for the decades of lost human capital. The second is to aggregate the reparation funds and allow African Americans to apply for grants for different asset-building projects. These projects could promote homeownership or education, for instance. Under this thinking, reparations should be more than one-time payments, but should build the human and wealth capital that black Americans struggled to gain over the past few centuries.

A third approach would be to give vouchers for a certain monetary value to black Americans. This mirrors the goal of the second approach, but with a focus on building financial assets. “Thus reparations could function as an avenue to undertake a racial redistribution of wealth akin to the mechanism used in Malaysia to build corporate ownership among the native Malays,” Darity and Frank write. “In that case, shares of stock were purchased by the state and placed in a trust for subsequent allocation to the native Malays.”

Fourth, the government could give African Americans in-kind reparations—free medical insurance or guaranteed college education, for instance. Finally, the fifth approach “would be to use reparations to build entirely new institutions to promote collective well-being in the black community.” Darity and Frank don’t elaborate on the potential structure for those institutions. Congress could also combine any or all of these approaches.

Who should be eligible to collect reparations?

Darity and Frank set out two criteria for eligibility: “First, individuals would have to establish that they are indeed descendants of persons formerly enslaved in the United States. Second, individuals would have to establish that at least 10 years prior to the adoption of a reparations program they self-identified as ‘black,’ ‘African American,’ ‘Negro,’ or ‘colored.’” These standards would undoubtedly create significant controversy for African Americans trying to prove their ancestry, but any eligibility criteria will be difficult to outline.

In researching the literature on reparations, I realized why Coates did not provide more details: He couldn’t. Economists simply have not made many estimates. That's reason enough for Congress to pass Conyers's bill. We can debate reparations all we want. But we can't decide whether to make reparations until we know exactly what doing so would entail.