Reform conservatives are having a moment. They managed to book some of the most powerful Republicans in Washington at an American Enterprise Institute event Thursday to celebrate a new compendium of essays called "Room To Grow," which charts a less plutocratic course for the Republican Party. And to hear Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam and other leaders of the conservative ideas industry tell it, the Republican Party is just a political heartbeat or two away from adopting a more middle-class and poor-friendly agenda.

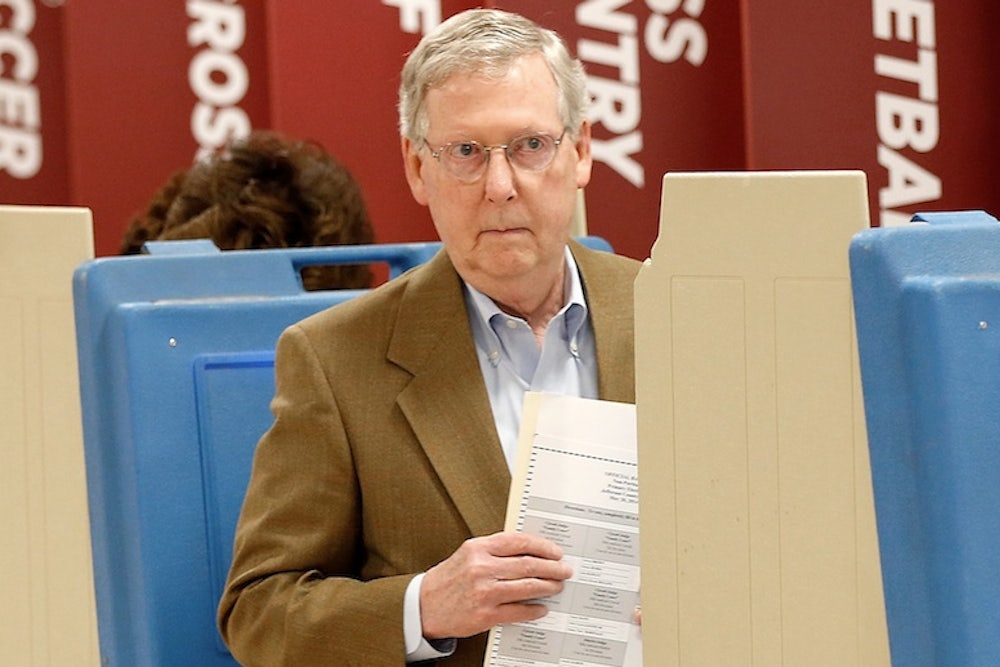

If I were a conservative reformer, though, I think I would've found the AEI confab a little depressing. Consider the timing. AEI billed the event to coincide with the 50th anniversary of LBJ's Great Society speech. But it also coincided with the end of the party's most hotly contested midterm election primaries, which, as luck would have it, the Republican establishment swept. Mitch McConnell—who was keynote speaker at the event—even made light of it.

"I'm happy to be here, especially under the present circumstances," he said. "If things had turned out differently in Kentucky Tuesday, this could have been a fairly awkward presentation."

McConnell is a big get. And it was genuinely funny to imagine the event organizers scrambling to account for it if their marquee speaker—the Senate Republican leader, a man with genuine influence over the party's agenda—had lost his job to a right winger on Tuesday. But it's also really hard to imagine McConnell or anyone of his stature agreeing to participate in an event like this, in an environment where the party's primary voters are controlling its agenda and its rhetoric. Which, unfortunately, is most of the time. That control just happened to ebb this very week. (Eric Cantor, whose primary is early next month, also participated in the event, but his isn't nearly as hotly contested as McConnell's was.)

Perhaps these kinds of events represent incremental steps toward a complete reimagining of the Republican agenda. But it's easier, in a way, to treat them as acts of mutually beneficial tokenism. Liberated from the constraints of GOP primary politics, Republican leaders get to soften their tone in a sober, decidedly non-Tea Party environment. Republicans, McConnell allowed, "have often lost sight of the fact that our average voter is not John Galt." Conservative policy experts get public praise from people who wield actual power—which, among other things, might lead to more grant money down the road. Not that reform conservatives are playing a cynical game, exactly, but that Republican leaders think of them as helpful messaging agents at key political moments, rather than as torchbearers. And everyone has an incentive to pretend otherwise. This may explain why (by my count) nobody at the event had anything to say about where in the GOP's constrained budget Republicans will find the money they'd need not just to hold the poor and middle-class harmless, but in some cases to augment their federal support.

Obviously you can't reform an entire political party by relentlessly projecting pessimism and hopelessness. But the ever-faithful routine conveys a real obliviousness to the possibility that the very people the reform conservatives hope to influence are treating them as useful fools.