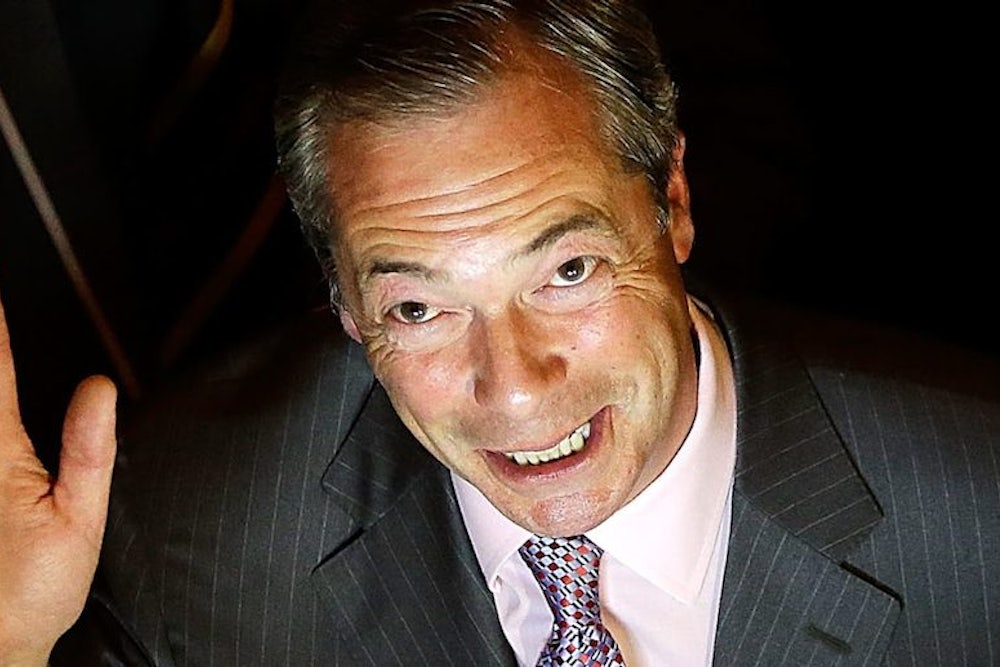

Nigel Farage’s approach to the European elections was not governed by conventional wisdom. While the Conservatives spent months downplaying expectations of their performance in the European elections, Farage was busy doing the opposite.

The European election results provided stunning vindication. The easy option would have been to set the U.K. Independence Party up as carefree underdogs, and try to replicate the strategy that yielded a second-placed finish in the 2009 European elections.

But Farage eschewed such expediency. The problem with 2009, for Ukip, is that running a low stakes campaign in a low stakes election meant that, after polling day, there wasn’t much left. A vote for Ukip was a cheap shot at the other parties, but it was forgotten in about the time it took to put a cross by Ukip’s box on the ballot paper. A year after the last European elections, Ukip had lost over four-fifths of their support.

So Farage opted for a different approach. He put pressure on Ukip at every turn. He shunned the expectation management approach. Farage made the elections high stakes—or at least as high stakes as European elections can be. This meant a more intense election campaign, and more scrutiny on the party. It created a formidable ‘Stop Ukip’ political machine.

For Farage, overcoming this is a significant achievement. His hope will be that voters have heard everything bad there is to say about Ukip, and that those who did vote for Ukip will not encounter any nasty surprises about the party before May 6 next year. Ukip is successfully tapping into the ‘left behind’ voters who Rob Ford and Matt Goodwin have identified as its most fertile group of supporters. And they did cared not for the anti-Ukip attacks. The more Farage and his party were attacked, the higher they polled.

Still, perspective is needed. Ukip came top, yes, but with 27.5 percent—and in an election in which turnout was a derisory 35 percent, 30 percent less than in the last general election. This “political earthquake” may yet do no more than mildly shake the cutlery. If Nigel Farage is serious about getting Ukip seats at the next general election, he will soon have to upset a lot of prominent party personnel. The party lacks the resources to target more than a dozen seats in 2015.

Farage will hope that the real legacy of this campaign is more than just a fleeting historical triumph for Ukip but the creation of a distinct brand of Ukip voters. Supporters who stayed with the party despite—or perhaps because of—the media onslaught and are more faithful than Ukip’s voters in the 2009 European elections. The reasons not to vote for Ukip have never been more known or better articulated. That so many voters overcame these will give Ukip hope that its vote will collapse less spectacularly than five years ago.

This piece originally appeared at newstatesman.com