I was at no risk of being in the tank for Matt Miller—no, not I. For one thing, I am a journalist, bound by the ethics for which my trade is admired. For another, politics is an odd business, and those who go into it are odd and egotistical people, not like me, a normal and virtuous journalist. Also, there was too much salivating in this race. When Democrat Henry Waxman announced in January that he’d be retiring from Congress, having represented much of Los Angeles County for 40 years, the effect was like granddad leaving behind a rent-controlled penthouse to an uncertain heir. (“I knew instantly in my gut that this district, the 33rd District, and his position was something I knew I could make a difference in”—pronouncement by City Hall politician Wendy Greuel, not a resident of the 33rd District.)

And yet Miller’s campaign interested me. In Los Angeles, Miller is a minor celebrity, best known for hosting a public-radio show called “Left, Right & Center.” And he has written two quite good books, The 2% Solution and The Tyranny of Dead Ideas. In the 1990s, he did some time in the Office of Management and Budget under President Clinton, followed by a stint at The New Republic, and today he does some private-sector consulting at McKinsey. In short, Miller’s a writer-wonk, a journalist—not, again, that this would make me partial to the man. On May 1, more than a month before the primary, Miller also picked up an endorsement from the Los Angeles Times, so if Miller had qualifications that I considered to be worthy, these were likewise noted by some of Miller’s most prominent fellow opinion journalists. So there.

Eight days before the primary, I headed out to watch the man campaign. The event took place in the backyard of a spacious house in Pacific Palisades, Miller’s own neighborhood, a wealthy pocket of hillside Los Angeles next to the ocean. Crossing a bridge over a koi pond at the entrance, I introduced myself to the host, Chuck Davis, a friend of Miller’s since the 1980s, when both were at Brown University. (I suspect Los Angeles is now run by alumni of Brown, but that is another story.) On hand for visitors, along with snacks and beverages, were stick-on tattoos that read, in black lettering, “MATT MILLER FOR CONGRESS! ENDORSED BY THE LOS ANGELES TIMES”—created because political consultant Stan Greenberg told Miller to tattoo the Times endorsement on his forehead. Of the couple dozen guests, nearly all over 40, several had applied the “Mattoo,” as the campaign called it, to various non-forehead parts of their body. I grabbed one and attached it to my clipboard.

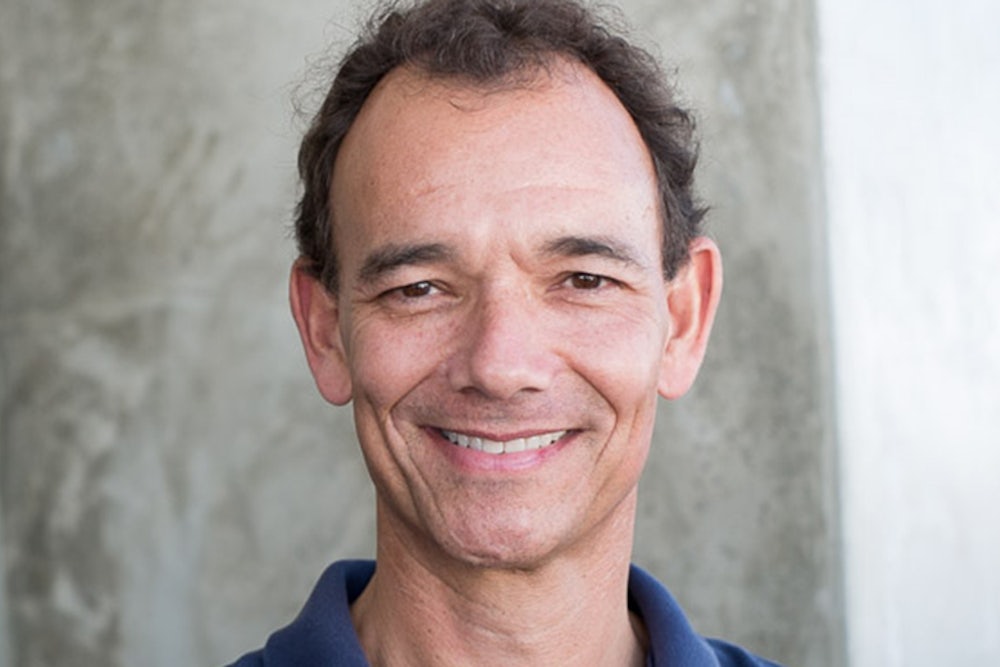

Miller is 52, tall and bespectacled, resembling a lean Norm Macdonald. That day, he wore gray slacks, frumpy black slip-on shoes, and a blue polo shirt that allowed his arm Mattoo to be visible. An audience member asked about Mattoo durability. “This has been through several days of showers,” he assured her. Then, after thanking his hosts, and, with a gesture toward a lush canyon view, noting “how many beautiful ways there are to live in Los Angeles,” Miller launched into his stump speech.

For the “center” of “Left, Right & Center,” he was surprisingly forceful, denouncing health care “oligopolies” and deploring how campaigns are financed. He proposed a wonky carbon tax that would rebate all the money to the taxpayer, and he said he would push the federal government to encourage teacher hiring policies similar to those in Singapore and Finland. He was also playful. Asked about lavish defense procurement, he said solemnly that we should “shrink the Pentagon down to the size of a triangle.” (He followed up with a serious answer.) Asked about gerrymandering and partisanship, he noted that he considered Rockefeller Republicans to be sadly endangered and urged that they be bred in captivity.

The questions he got were much more substantive than what journalists would ask, and the answers he gave were much more thoughtful than what normal candidates would provide. He explained that he wanted to be on the budget committee in order to take advantage of those brief intervals every two to four years when there is a window for meaningful action. Unlike just about any candidate, he wrote his own policy papers, and a number of his proposals used ideas blessed by conservatives, in order to make prospects of passage more likely.

Cover enough campaigns and you realize that entering politics in earnest is like a promise to amputate everything interesting about yourself. It is a vow of hack. But I had to admit that politics did not seem to have destroyed Matt Miller. I eyed my Mattoo. Would it be unprofessional to wear one, just for reporting purposes?

When I returned home, I scrolled over to see what Miller’s chief rivals, the presumptive Democratic front-runners, were saying. Greuel had taken to her Facebook page to condemn Clippers owner Donald Sterling for racist taped remarks (“disgusting and disgraceful”), to condemn an odious poster drawn up by opponents of Texas gubernatorial candidate Wendy Davis (“deeply offensive”), and to assure voters of her commitment to “work tirelessly to preserve and strengthen Social Security and Medicare.” State Senator Ted Lieu had taken to Facebook to condemn the recent scandal over wait times at V.A. hospitals (“shocking and unacceptable”), to condemn child sex-trafficking (“Our children are not for sale”), and to assure voters of his commitment “to protect medicare & social security.”

Five days later, I joined Miller and his campaign’s chief of staff, Ben Sherman, to watch Miller canvas at the Santa Monica Farmers Market. Much swallowing of pride is required of a candidate at such times.

Miller: Hi, I’m running for Congress. Do you live in the area?

Woman: No.

Miller: Hi, I’m running for Congress. Do you live in the area?

Couple: [Silent staring ahead and walking.]

Miller: Hi, I’m running for Congress. Do you live in the area?

Couple: No, France!

I asked Miller if it was hard to approach people out of the blue; he said he enjoyed it. “Hey there, good-looking,” Miller said to a lady walking the other way. “Do you live in the area?” It was Jody Miller, Matt’s wife. She’d had luck with some of the market-goers, she said, and she reported that one elderly lady seated nearby had offered her vote in exchange for Jody’s dress. “Take it off,” Matt ordered.

In his studies of optimism, psychologist Martin Seligman has found that pessimists are more likely to be realistic than optimists are. This can be useful in financial planning; but in politics, optimism is best. Matt Miller estimated that half of his approaches were successful in at least getting out the word. I estimated that about a fifth were. Jody Miller said she didn’t expect so many out-of-area tourists to be at the market. I thought I didn’t expect so many liars to be at the market. Still, he’d connected with at least a couple dozen interested people, and one had even volunteered to man phones.

I don’t want to say that I was becoming a silent cheerleader at this point. For instance, when Miller made another campaign appearance and observed that many of his fellow Democrats were leaning on “values-based appeals without doing anything that changes the conditions or the prospects of ordinary Americans,” I didn’t mouth, “Woo-hoo,” or raise my fist. That would have been unprofessional, plus I was holding a drink. But still. Could a non-hack really make the cut?

Three days later, it was time for the primaries. I slept poorly on Monday, but surely just because I’d had late coffee. On Tuesday night, impatient, I checked my laptop, but no final results. The next day, I saw that Matt Miller had not made it into the top two. He’d come in a respectable fifth, with 12 percent of the vote. Democrat Ted Lieu had secured a run-off spot, with 19 percent of the vote, and so had a Republican named Elan Carr, with 22 percent. Only 13 percent of voters had participated—the usual.

I checked Carr’s campaign page and found that he had taken to Facebook to condemn the Holocaust (“one of history’s most despicable atrocities”), to condemn cruelty to animals (“people who intentionally torture animals should go to state prison”), and to invite supporters to a $1,000-per-plate dinner “hosted by my friends Sheldon and Miriam Adelson at the Four Seasons Beverly Hills.”

Life as we know it had resumed.

On Thursday morning, Miller and I met up for a cup of coffee in Pacific Palisades, and there was no mistaking the comedown. As I asked him about insights and plans, he noted evenly that, 24 hours out, he’d not had a lot of time for reflection. He was going to take a vacation with his wife and daughter. But he was happy he’d given it a try. “I think politics is a really worthy calling,” he said. “If good people don’t do this, how do we expect anything to get better?”

Once again, victory had gone to the standard sorts. Still, I confess: Some of us might have come out less jaded. For all the grubbiness, apathy, bribery, hackery, and phoniness in the game, for all the votes to be gained by a firm stance against cat torture, American democracy still works well enough that getting involved tends to make you less, not more, cynical. Miller had lost, just as we’d known he would. But he’d done remarkably well in a four-month campaign, raising more than $800,000, and, with twice the time, he might have come in fourth. Or better. Right?