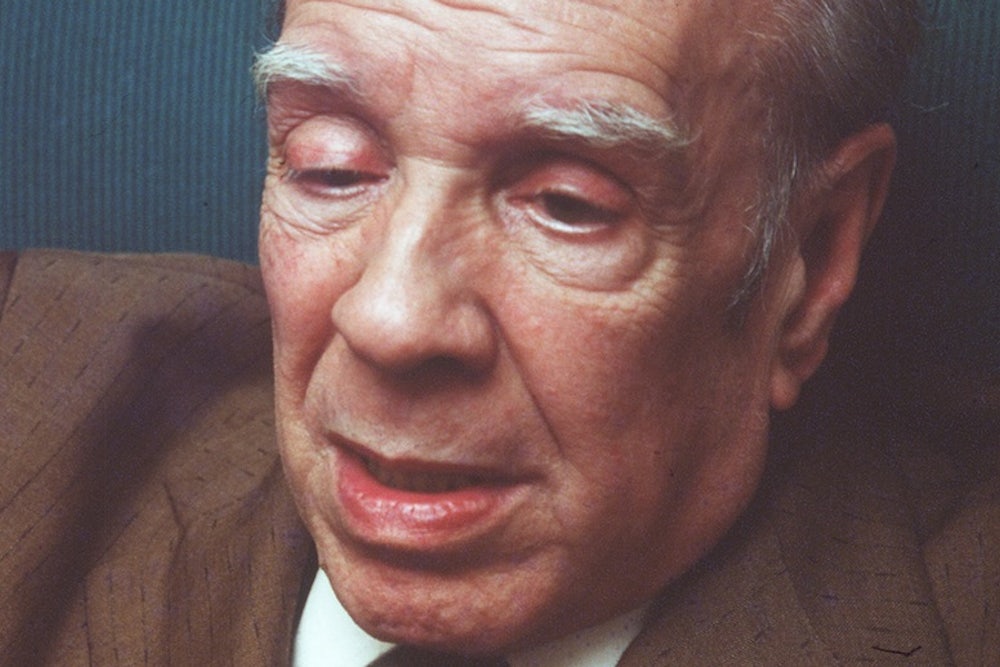

“Soccer is popular,” Jorge Luis Borges observed, “because stupidity is popular.”

At first glance, the Argentine writer’s animus toward “the beautiful game” seems to reflect the attitude of today’s typical soccer hater, whose lazy gibes have almost become a refrain by now: Soccer is boring. There are too many tie scores. I can’t stand the fake injuries.

And it’s true: Borges did call soccer “aesthetically ugly.” He did say, “Soccer is one of England’s biggest crimes.” And apparently, he even scheduled one of his lectures so that it would intentionally conflict with Argentina’s first game of the 1978 World Cup. But Borges’ distaste for the sport stemmed from something far more troubling than aesthetics. His problem was with soccer fan culture, which he linked to the kind of blind popular support that propped up the leaders of the twentieth century’s most horrifying political movements. In his lifetime, he saw elements of fascism, Peronism, and even anti-Semitism emerge in the Argentinean political sphere, so his intense suspicion of popular political movements and mass culture—the apogee of which, in Argentina, is soccer—makes a lot of sense. (“There is an idea of supremacy, of power, [in soccer] that seems horrible to me,” he once wrote.) Borges opposed dogmatism in any shape or form, so he was naturally suspicious of his countrymen’s unqualified devotion to any doctrine or religion—even to their dear albiceleste.

Soccer is inextricably tied to nationalism, another one of Borges’ objections to the sport. “Nationalism only allows for affirmations, and every doctrine that discards doubt, negation, is a form of fanaticism and stupidity,” he said. National teams generate nationalistic fervor, creating the possibility for an unscrupulous government to use a star player as a mouthpiece to legitimize itself. In fact, that’s precisely what happened with one of the greatest players ever: Pelé. “Even as his government rounded up political dissidents, it also produced a giant poster of Pelé straining to head the ball through the goal, accompanied by the slogan Ninguém mais segura este país: Nobody can stop this country now,” writes Dave Zirin in his new book, Brazil’s Dance with the Devil. Governments, such as the Brazilian military dictatorship that Pelé played under, can take advantage of the bond that fans share with their national teams to drum up popular support, and this is what Borges feared—and resented—about the sport.

His short story, “Esse Est Percipi” (Latin for “to be is to be perceived”), also may explain his hatred of soccer. About halfway through the story, it’s revealed that soccer in Argentina has ceased to be a sport and entered the realm of spectacle. In this fictional universe, simulacra reigns supreme: the representation of sport has replaced actual sport. “These [sports] don’t exist outside the recording studios and newspaper offices,” a soccer club president huffs. Soccer inspires a fanaticism so deep that supporters will follow nonexistent games on TV and the radio without questioning a thing:

The stadiums have long since been condemned and are falling to pieces. Nowadays everything is staged on the television and radio. The bogus excitement of the sportscaster—hasn’t it ever made you suspect that everything is humbug? The last time a soccer match was played in Buenos Aires was on 24 June 1937. From that exact moment, soccer, along with the whole gamut of sports, belongs to the genre of the drama, performed by a single man in a booth or by actors in jerseys before the TV cameras.

This story goes back to Borges’ discomfort with mass movements: “Esse Est Percipi” effectively accuses the media of complicity in the creation of a mass culture that reveres soccer, and, as a result, leaves itself open to demagoguery and manipulation.

According to Borges, humans feel the need to belong to a grand universal plan, something bigger than ourselves. Religion does it for some people, soccer for others. Characters in the Borgesian corpus often grapple with this desire, turning to ideologues or movements to disastrous effect: The narrator of the story “Deutsches Requiem” becomes a Nazi, while in “The Lottery in Babylon” and “The Congress,” small, innocuous-seeming organizations quickly transform into vast, totalitarian bureaucracies that dole out corporal punishment or burn books. We want to be a part of something bigger, so much so that we blind ourselves to the flaws that develop in these grand plans—or the flaws that were inherent to them all along. And yet, as the narrator of “The Congress” reminds us, the allure of these grand narratives often proves too much: “What really matters is having felt that our plan, which more than once we made a joke of, really and secretly existed and was the world and ourselves.”

That sentence could accurately describe how millions of people on Earth feel about soccer.