What kind of world is left in the wake of an event that snatches 2 percent of the entire population out of thin air? The Leftovers, a new HBO series based on the 2011 novel by Tom Perrotta, looks at the lives of Mapleton, New York residents three years after a massive disappearance. The thin veneer of secrecy that protects the foundation of humanity is slowly peeled away, and an insidious violence is left in its place; neighborly trust has been replaced by a low level mistrust, and everyone seems to operate from the same central point of uncertainty.

The disappearance, thought by some to be The Rapture, is never explicitly called that, instead referred to as “the sudden departure.” In the first few episodes you never see the departure happen, which is part of the immediately unsettling vibe of the show; a baby is crying, then it is gone, without the sparkly dust or twinkling piano that usually accompanies these things on traditional TV shows. But religion still creeps into the event, as those left behind want to know what happened to their loved ones. Did they go to heaven? Why them? Why not me?

No one questions this more than Reverend Matt Jamison (Christopher Eccleston), who, after dedicating his life to the church, makes it his mission to out the sins of the departed as a way to justify not being among them. Church attendance is suffering, and the reverend is working—desperately—to keep it afloat amid his own personal problems. But his efforts are met with a mixture of annoyance and disdain; the occasional physical attack is thrown in for good measure. In the landscape of this new world, formerly religious people feel slighted, and non-believers have less of a reason to believe in God than ever before. God offers little comfort when everyone you love has been taken away from you.

It is to the credit of the show that it’s not just the families that have lost someone who experience pain. Police chief Kevin Garvey (Justin Theroux) is an unmitigated mess; even though his wife and two children are still alive, they’ve been completely ripped apart by the departure. With his thick New York accent and emotional instability, Theroux is believable as a reluctant leader who becomes increasingly, and terrifyingly, unhinged. The pressing responsibility of raising his sullen 16-year old daughter Jill (Margaret Qualley) seems like a heavy weight that has fallen on him, even though you get the feeling he’d be ill-equipped to handle the job even in the best of times.

Jill, for her part, is doing her best to navigate the post-departure terrain—a minefield of recklessness and sex, not to mention the normal teenage girl stuff. Her older brother Tom (Chris Zylka) has dropped out of college to follow Holy Wayne (Paterson Joseph), a newfangled cult leader who claims he can hug the pain out of people but mostly resorts to statutory rape and extorting money out of senators. In short succession, Tom falls victim to a power play by the guru that leaves him responsible for Christine, one of Wayne’s young lovers, and deeply separated from his family. Tom seems to lack the machismo his father relies upon, and he seems lost in a world where he doesn’t have a clear map to adulthood.

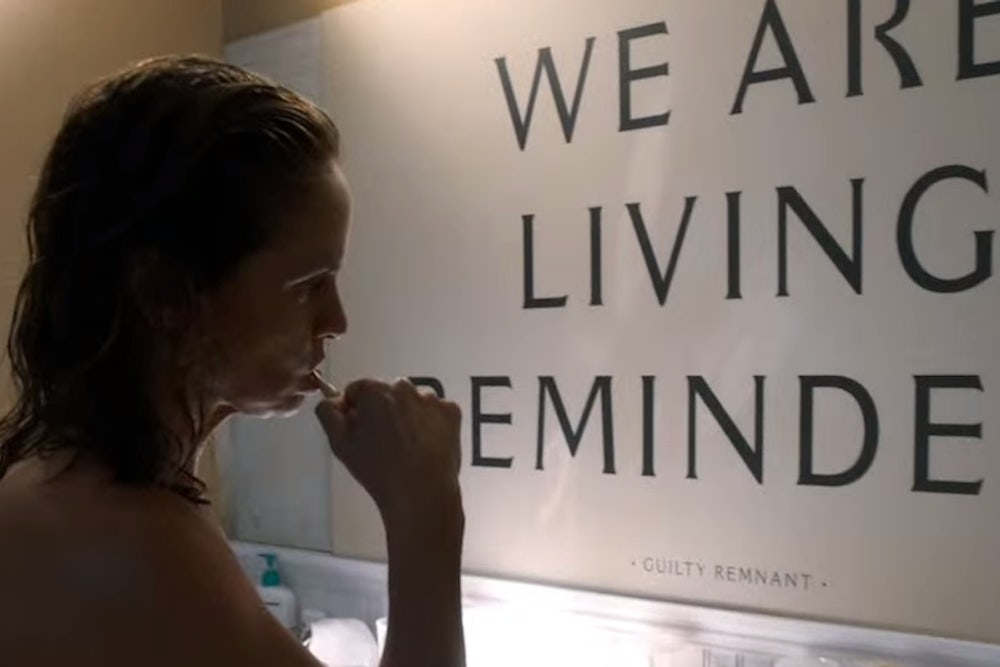

Kevin’s wife, Laurie Garvey (Amy Brenneman) is the most interesting character in the Garvey clan. She still lives in Mapleton, but has moved in with the Guilty Remnant, a cult-like sect of 50 people who live on the same cul-de-sac, wear all white, chain smoke, and haunt everyone else in town by silently stalking them from 20 feet away. What makes someone take a vow of silence and leave their family behind? In one episode, Patti (Ann Dowd), the apparent leader of the Guilty Remnant, tells Laurie that their job is to remind people of the things they would rather forget; they show up at Heroes Day, an event organized by the mayor to salute the departed, with signs that say “Stop Wasting Your Breath,” their ominous silence punctuating the grief-stricken crowd. The Guilty Remnant are menacing, but only in that they bring into sharp focus the hatred and anger hiding just under the surface. Loss is a permanent complication that everyone is learning to maneuver around.

It took me a while to get used to the emotional violence of The Leftovers, but that’s where having a cohesive cast works best for this show. I had a similar feeling that stayed with me for a while after I read the book a few years ago; these friends and neighbors become inherently hostile and defensive, it makes you wonder if our great social experiment is doomed to fail. It’s not necessarily a violence they are perpetrating on each other, but the repercussions of it are instantly tied to other people. The eerily silent moment when two people throw themselves off of a building cascades into a major life decision for Tom; an updated game of Spin the Bottle that has Jill lazily choking a boy while he masturbates and she cries is indicative of a complete emotional disconnect even where there is physical contact. The show isn’t terribly graphic, which makes these punctuated moments of brutality all the more terrible; they slip in unexpectedly, between quiet moments.

Director and executive producer Peter Berg brings the same heightened sense of nuance to this show as he did to Friday Night Lights, and I’m learning to trust Damon Lindelof again after the disastrous ending of Lost. But if we are reassured by the competent technical components of the show, its material leaves an unsettling impression. This show is not about the end of the world, even though the world as the characters knew it has clearly ended. People try to jam themselves into the outfit of their former lives, but the clothes just don’t fit anymore. Cheerleaders practicing in the high school hallway seem crude; planning a wedding seems somehow offensive. The packs of wild dogs are as close as you get to zombies, but even they are the effect of the apathy affecting the humans. The underlying tension of the show is that the post-apocalyptic landscape might look like our everyday lives.

“Where were you when it happened?” is a question the people of Mapleton ask each other a lot; it’s both a conversation starter, and a plea. There are small mysteries to be solved—why do the Guilty Remnants smoke so damn much?—but the overarching question the show is trying to answer seems to be “How do you survive surviving?”