As you might expect from the author of songs like “Love Story,” “Enchanted,” and “Today was a Fairytale,” the piece Taylor Swift wrote for the Wall Street Journal this week was unashamedly upbeat. She’s optimistic about the future of the music industry (it “is not dying … it's just coming alive”), about the relationship between artists and fans (she compares it to a marriage, and says it’s only made more intimate by social media), even about diminishing album sales (they “challenge and motivate” musicians to push themselves). All of which makes it striking that she has a gloomy outlook on what was once a staple of the music business: the autograph.

“There are a few things I have witnessed becoming obsolete in the past few years, the first being autographs,” she wrote. (She doesn’t say what any of these other “few things” are.) “I haven't been asked for an autograph since the invention of the iPhone with a front-facing camera. The only memento ‘kids these days’ want is a selfie.”

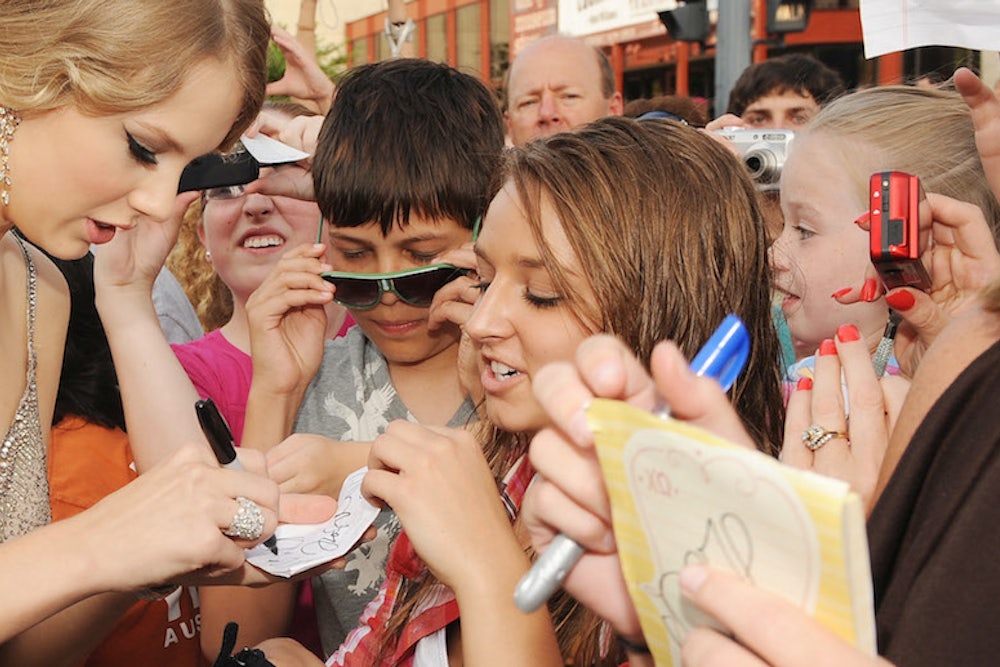

This is not quite true. As Businessweek points out, Swift is regularly spotted signing autographs for fans, and she sells signed merchandise on her website. But she may have a point about the decline of the autograph in general.

“It is absolutely true that there’s less demand for autographs,” says Michael Hecht, a financial advisor at Morgan Stanley who, for the past ten years, has also served as president of the Universal Autograph Collectors Club (UACC), one of the largest autograph societies in the world. “There’s a diminishing demand for print journalism. There’s a diminishing demand for stamps. There’s a diminishing demand for autographs.”

Autograph collecting began gaining popularity as an American pastime in the nineteenth century, alongside a growing interest in antiquarianism; among the literate upper classes, elaborate autograph collections, like “cabinets of curiosities,” emerged as markers of status and wealth. A reverend named William Buell Sprague is usually cited as the owner of the first American autograph collection: While working as a live-in tutor at George Washington’s family estate, he asked a nephew if he could keep some of Washington’s signed letters. No one objected when he made off with around 1,500. In the mid-nineteenth century, trendy autograph collectors tried to obtain documents signed by all 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence. Today, Hecht says, collecting all the presidents is the goal of many ambitious autograph collectors.

Hecht, who has been collecting autographs for 45 years, has watched membership to the UACC—which was founded in 1965—steadily decline during his tenure. Subscriptions to the UACC’s magazine, Pen and Quill, have fallen from a peak of around 2,000 in the year 2000 to 700 today. (Subscribers fork over $29 a year for the quarterly magazine, which publishes articles on how to tell if an autograph is authentic and offers tips on which celebrities don’t mind being approached for autographs.) When I asked Hecht about the demographics of his club, he answered in one word: “Old.” Autograph collectors also seem to be overwhelmingly male: Eight of the nine staff members of UACC are men.

Hecht believes Swift is right to pin part of the blame on the rise of selfies. “As we become more and more of a visual society, people want a visual representation of their favorite stars. We don't know them through their writing, through their letters; we know them by their faces.”

Andy Alas, a dentist who has been collecting autographs since 1989 and has served on the board of the UACC in the past, says he’s noticed a change too. “At autograph shows, you used to pay for only the autograph. Actors and writers were happy to pose for a picture with you for free. Nowadays, most charge for the opportunity. I see people attend book signings and autograph shows with no intention of purchasing a book or other signed item. They come armed only with their cells phones.”

Selfies may be more popular with tweens, but for serious autograph collectors, nothing beats the thrill of owning something signed by a personal hero.

“People collect autographs to touch history or to touch a person who they admire,” says Hecht. “They want something that shows this person really was alive.” The two autographs Hecht cherishes the most are from his father and Abraham Lincoln.

Industry experts like Hecht and Kevin Segall, an appraiser and dealer at Collector’s Shangri-la in Woodland Hills, California, are confident that selfies won’t affect demand for historical autographs. Hecht says the most sought-after autographs belong to historical figures like Shakespeare, Lincoln, and Washington. The star of Segall’s collection is a memo signed by all four Marx brothers. “It’s about that connection with people you really admire,” said Segall. “It’s an ineffable experience.”

“The price of Washington and Lincoln have gone up every year since I’ve been a collector,” said Hecht. “The only time they went down was during the depression. Admiration continues from decade to decade and generation to generation.”

If the point of an autograph is to show off a personal connection with a star, then a selfie that can be shared on Facebook or Twitter is more apt than an autograph. If the goal is to have something that may gain monetary value, then selfies are worthless. Truly devoted fans, one dealer told me, combine both trends: They take pictures with celebrities, then return to get their selfies signed.