The political media's handicapping of the November 4 midterm election has contributed to the impression, fostered by many partisans and commentators, that the stakes have never been higher. Jonathan Capehart, the liberal Washington Post columnist, says he wants to “warn” Democrats that “President Obama will be impeached if the Democrats lose control of the U.S. Senate.” Republican Senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma believes a GOP Senate will finally blow the lid off “the greatest coverup in American history”—that is, Benghazi.

In fact, the stakes rarely have been as low as they are this year—even if Republicans do win back the Senate.

The 1994 midterm election produced dramatic political change: a Republican House majority for the first time in 40 years and a GOP Senate majority for the first time since 1986. GOP losses in the 1998 midterm, despite retaining the House majority, cost Newt Gingrich the speakership and delivered a rebuke to the party's effort to oust President Bill Clinton for his sexual adventurism.

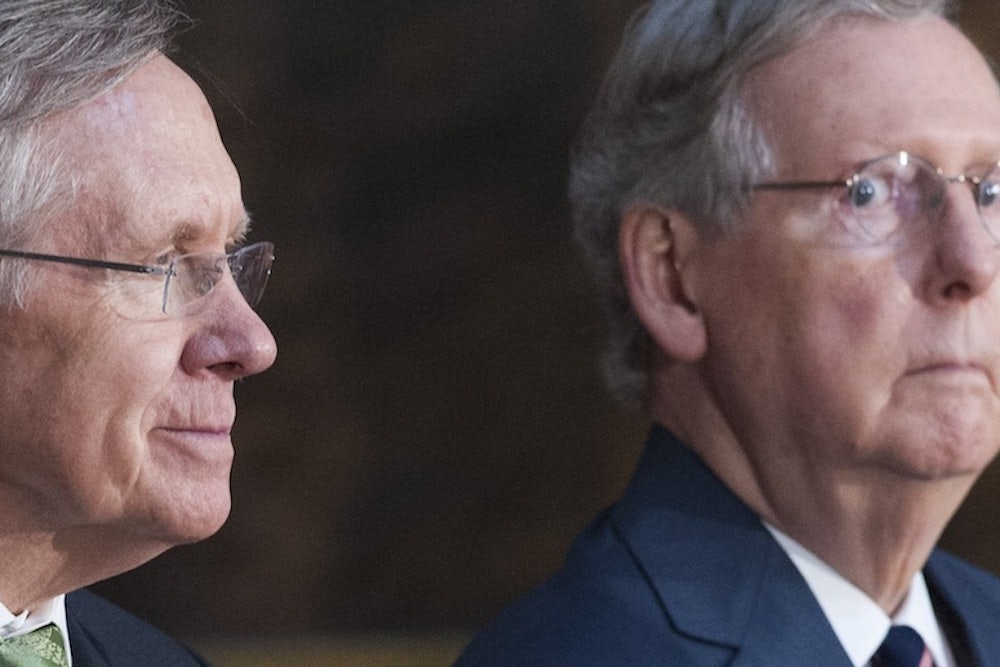

In 2006, Democrats swept away the GOP in both the House and Senate. With Obama’s election in 2008, Congress was prepared to pass health-care reform, a task that had proven impossible despite the Democrat-controlled House and Senate in the first two years of Clinton’s first term. In 2010, the Republicans surged back, retaking the House but not the Senate (owing largely to the GOP's nomination of unelectably right-wing and strange candidates in several key states, not least Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s Nevada).

It’s quite possible that the GOP will pick up enough Senate seats in November to control the chamber. But the real potential for drama and consequence for the 2014 midterm now seems all but a dead letter—namely, that Democrats would somehow recapture the House. This was never a bet for the faint-hearted, as the historical trend favors gains for the opposition party (with exceptions like 1998). Yet the extraordinary tech prowess of Obama’s team in turning out voters for his reelection in 2012 at least raised the possibility that the campaign’s database, transmogrified from “Obama for America” to “Organizing for America,” could work magic in the midterm as well.

But that was before Obama’s second-term political fortunes took a turn for the worse, starting with the stubbornly lackluster economy, proceeding to the disastrous Obamacare rollout, and now with a deteriorating international environment and uncertainty about U.S. leadership. Not even the record-low disapproval of Congress has been enough to counterbalance the decline of Obama’s own disapproval rating and of Democrats’ prospects for pulling an epic upset.

Even a GOP victory in the Senate wouldn't be enough to brand 2014 an election of consequence. This would make very little difference to the balance of power in Washington, which already has its two most salient characteristics carved in stone for the remainder of Obama’s term: divided government, and a very deep unwillingness to work across the aisle.

True, a GOP-controlled Senate would launch a few more investigations of the Obama administration's misdeeds, real and imagined. But the House already has such investigations underway, and with all due respect to “the world’s greatest deliberative body,” an investigation that proceeds with support strictly along party lines is no more credible when the Senate is doing it. The confirmation process for judicial nominees was going to slow down in the final two years of the administration anyway. Other administration appointments simply don’t matter all that much this late in the term, and even a GOP-controlled Senate will face pressure to approve some nominees for appearance’s sake.

Legislation that passes the GOP House will get consideration in the Senate rather than the high-handed dismissal with which Reid has greeted it. Yet the filibuster rule requiring 60 votes for legislation to proceed in the Senate remains intact, and it’s unclear that a GOP Senate majority would blow it up—especially since Obama can veto anything that Congress passes. And he will. Neither the House nor the Senate has the capacity to override a presidential veto if his vote becomes a test of partisan loyalty; Democrats will surely be able to muster one-third of the House or Senate to sustain a presidential veto.

Obama might find himself in the position of vetoing politically popular legislation, especially if something came to his desk with enough support from Senate Democrats to get past a filibuster. But this assumes a GOP-dominated legislative process is, in fact, capable of producing popular legislation. That’s not clear, especially if social-issues conservatives seize the initiative.

Let's suppose, though, that Congress passes an increase in the defense budget, currently under severe strain from sequestration. Such a bill might indeed be popular, especially with international instability on the rise. On the other hand, the administration would have little difficulty describing such a GOP-crafted bill as unbalanced and out of sync with other national priorities (i.e., Democratic priorities). Such an argument would be convincing to most Democrats, and that’s enough.

Each party keeps looking to the next election to provide a decisive edge, but elections aren’t doing that. If the Senate flips in 2014, not much else is likely to change with it. As long as both sides see greater political advantage in inaction than in working together, there is no way out of this polarized, mistrustful standoff. And if Democrats have become all but invincible running for president, while Republicans, for structural reasons, keep holding onto the House, this might be the state of affairs for quite some time.