This week began with news of the apocalypse, and it had nothing to do with the fact that the World Cup is over. On Monday morning, Washington’s insiders woke up to a “Playbook” newsletter citing another newsletter—this one for clients of the investment firm Southwest Securities—titled “A Weekend of Chaos.” “There is too much going on, which is too widespread and too serious to be ignored for long by the markets,” the newsletter said. “We have the constant threat of terrorism at our doorsteps.” On the Wall Street Journal’s front page a story sounded a similar alarm: “Obama Contends With Arc of Instability Unseen Since '70s.”

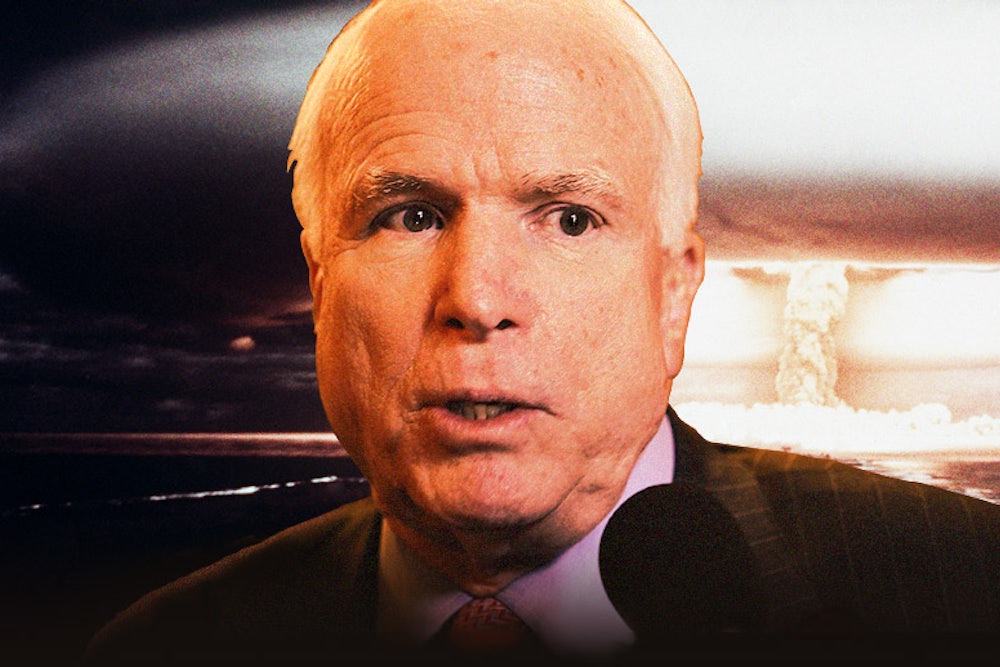

The surprising thing about this article wasn’t that it took two reporters to write. It was that it cited, as proof of this once-in-a-generation apocalypse, alarmist-in-chief John McCain: "Sen. John McCain (R., Ariz.), in a CNN interview Sunday, said the world is ‘in greater turmoil than at any time in my lifetime.’"

That’s a shocking statement for a man born in 1936—a man whose lifetime spanned the entirety of World War II and who was, let’s recall, a prisoner of war in Vietnam. As for that headline, let’s also recall all the unstable things that have happened since the 1970s: the Iran-Iraq War, Israel’s long fight over its borders, Lebanon’s civil war, the collapse of the Soviet Union (with its massive nuclear arsenal), the violent dissolution of a country named Yugoslavia, the end of apartheid, the genocide in Rwanda, the rise of China, the fall of Japan, the reign of the Taliban, the unraveling of Yemen and Pakistan, 9/11, the U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, Russia’s invasion of Georgia, the drug wars in Mexico and Colombia, and the Arab Spring, just to name a few.

Through all of that, America has remained intact and mostly healthy. And as for the assumed global consequences of all those events—a democratic Russia or Iraq, dirty nuclear weapons landing in our shopping malls—well, not very many of them have come to pass. What’s more, we’ve forgotten that we ever thought they were likely to happen. And yet, we continue, generation in, generation out, to watch the sky, sure that it is falling, and certain that we know exactly which way it’s going to fall.

Perpetual anticipation of the apocalypse is something of an American specialty. The U.S. was founded as an answer to the corruption and chaos of Europe. The Puritans believed that their “city on a hill” was the new Jerusalem. The idea that a small group of people have a unique access to the horrible truth, says Anthony Grafton, a professor of history at Princeton, “goes right back to the Book of Revelation.” These millenarian strains came to the fore in the First Great Awakening, when people believed that Christ would return to earth: first stop, America.

In the nineteenth century, while America was busy industrializing, Europe experienced wave after wave of revolution.“It looked like the mob was making a bid to take over Europe,” says Peter Shulman, who teaches American history at Case Western University. America eyed Europe warily; the apocalypse was happening just across the ocean. “At least in the nineteenth century, Americans often saw events abroad as either vindicating or threatening their own project,” Shulman says. Closer to home, apocalyptic language “was used to prepare for the coming of the Civil War,” Grafton says. “In that case it was appropriate.”

But more often, our use of apocalyptic language is just egotistical: Every generation believes it is witnessing a unique—and uniquely terrifying—degree of disarray. “Every generation that I know of, almost, has been convinced that somehow everything was going to hell in a hand basket,” says Tia Kolbaba, a Byzantine historian who teaches religion at Rutgers. “I suspect there are periods in history when people think things are on the up and up, but people have always been saying that this the end of culture, and that this is the end of everything that is good since, well,”—she pauses—“Cato the Elder, who thought that the Greek influence of Rome was the end of Rome.” Cato the Elder died in 149 B.C.E.; the decline of Rome is generally dated to about 450 years later. “That’s the other thing about decline,” she says, “if you take a long enough view, those people can always be right."

In early modern Europe, according to Grafton, people were also constantly predicting the end. In 1584 and 1604, for instance, due to a particularly fiery “conjunction” of Jupiter and Saturn, things on earth were supposed to get rather messy. Usually, catastrophe was averted, though one French astrological historian from the early fifteenth century said that the world would end in 1789. These weren’t just your standard pre-modern preoccupations with astrologically ordained apocalypse. Geopolitical worries kept people up at night, too. Back then, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Turks were on the march. They had taken Constantinople and, a couple times, they almost took Vienna. All of Europe, people predicted, would fall to the Saracens and all would be forced to convert to Islam.

All this is not so different, really, from our current "arcs of instability." We see crisis where we want to. In 1956, Grafton recalls, there was a fear that Adlai Stevenson’s loss to Ike had doomed Western civilization. (He was only six at the time, so, he says, “it must have really been the talk” if it penetrated his consciousness.) There was also fear that black-and-white television was the end of culture, and that comic books were no better. There was the loss of Vietnam to a Communist horde, the destruction of the American city. “The prediction back then was that ruin of the cities was going to continue, that every place will look like Detroit,” Grafton says.

The opposite of fear, of crisis, and of apocalypse, of course, is control. But so far, the twenty-first century has proven that “control” is a dubious, if not quixotic, proposition. And even when the “apocalypse” does arrive, it isn’t always that bad—nor does it look the way we expect it to. The loss of Adlai Stevenson ended up not being such a big deal; comic books have become art. (The British Library is hosting a major exhibit of them.) America has seen a massive urban renaissance, and Detroit is the exception, not the rule. “Because you just don’t understand how things are going to go,” Grafton says. “I can’t imagine a single pundit predicting, as the Vietnam War was coming to an end, that we would be on friendly terms with Vietnam and that it would be using relatively cheap labor to pull itself forward.”

It’s not that things will always work out for the best and that there’s no need to worry; it’s that, at least in the U.S., the worst outcome is not always the most likely one. But we love to believe in our own uniqueness, that we are the generation that is finally “standing at Armageddon,” and trying to control its fallout with our wild and inaccurate prognostications. Says Shulman, “We're really a very fearful people.”