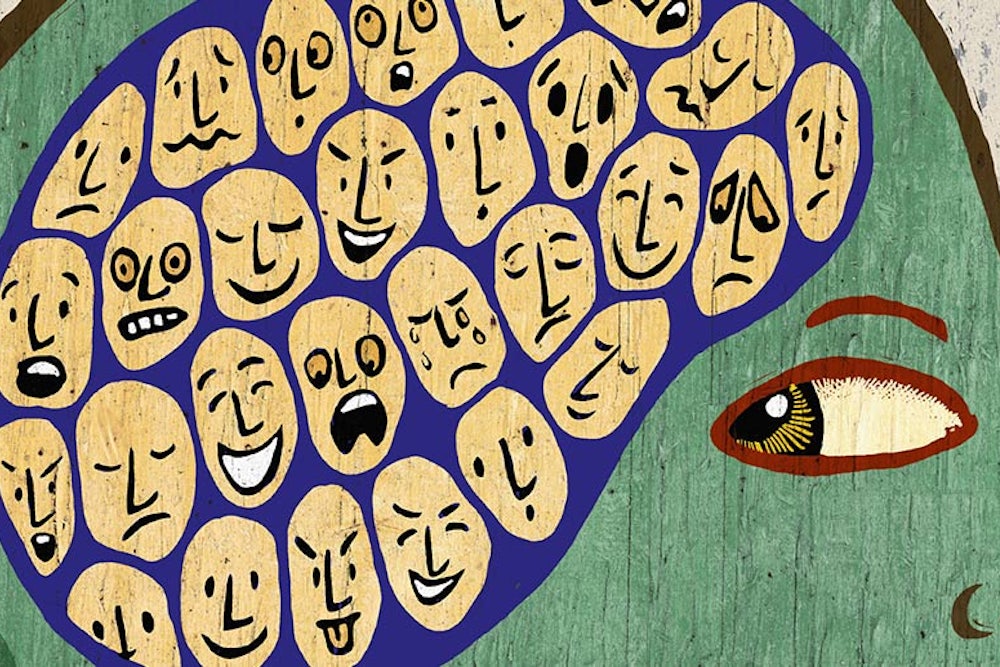

How we define mental illness is one of the most fraught issues in psychiatry; skeptics of the psychiatric establishment fear that broad definitions of mental illness could make people see their symptoms as more problematic than necessary. A small new paper in the British Journal of Psychiatry adds to the debate, offering a new perspective on how schizophrenia is experienced across cultures.

Stanford anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann worked with a team of psychologists to interview 20 schizophrenics in three cities: San Mateo, California; Accra, Ghana; and Chennai, India. Most of the patients were in their thirties or forties and had been ill for years. There were important similarities across the board—almost everyone reported a mix of positive and negative experiences with their voices—but there were several cross-cultural differences in how patients experienced and interpreted their symptoms.

Schizophrenics in California reported the most negative feelings about their voices; everyone Lurhmann spoke to used clinical language when talking about their voices, and no one said the overall experience was positive. Fourteen of the 20 patients admitted that their voices told them to hurt themselves or others. “Usually, it’s like torturing people, to take their eye out with a fork, or cut someone’s head and drink their blood, really nasty stuff,” said one. Only a few patients said they had personal relationships with the voices; just two regularly heard family members. Eight could never figure out who was speaking to them, and resorted to giving them abstract names like “Entity.”

In Ghana and India, patients’ experiences of schizophrenia were, relatively, more positive. They were more likely to report having intimate—and, they felt, constructive—relationships with the voices in their heads. In Chennai, interviewees rarely used clinical language like “schizophrenia” or “disorder.” Most—13 out of 20—regularly heard the voices of family members. “These voices behaved as relatives do: they gave guidance, but they also scolded,” writes Luhrmann. “They often gave commands to do domestic tasks. Although people did not always like them, they spoke about them as relationships.” Only four said their voices told them to do anything violent, and nearly half said their voices were, overall, a good thing. “I like my mother’s voice,” said one woman. “I have a companion to talk [to],” said another. Only two Ghanaians said their voices tried to incite them to violence; just two used diagnostic labels, and half said the experience of hearing voices was overall positive. Most—16—heard voices they attributed to gods or disembodied spirits.

“We believe that these social expectations about minds and persons may shape the voice-hearing experience,” wrote the authors. “The difference seems to be that the Chennai and Accra participants were more comfortable interpreting their voices as relationships and not as the sign of a violated mind.” The American cultural emphasis on autonomy, the authors went on to hypothesize, shapes “not only a clinical culture in which patients have the right to know, and should know, their diagnosis, but a more general cognitive bias that unusual auditory events are symptoms, rather than people or spirits.”