The Man Who Couldn’t Stop: OCD and the True Story of a Life Lost in Thought

David Adam

Picador, 336pp, £16.99

Black Rainbow: How Words Healed Me – My Journey Through Depression

Rachel Kelly

Yellow Kite, 304pp, £16.99

My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread and the Search for Peace of Mind

Scott Stossel

William Heinemann, 416pp, £20

As the numbers of people diagnosed with mental disorders rise, so do the numbers of books by sufferers describing the terror of their condition and their personal pilgrimage towards something at least resembling a cure—or at least a managed easing of their worst pain.

In The Man Who Couldn’t Stop, the journalist David Adam describes how intrusive thoughts take him over. They won’t leave him alone, and as they repeat, grow dark wings and proliferate, they plunge him into panic and despairing anxiety. The smallest scratch leaves him convinced he will develop AIDS. No argument, not even his own, will reason him out of his unreason. He lives in a state of siege.

To defy the imminent disaster that obsesses him, Adam resorts to compulsive actions, checking and rechecking possible sources of HIV infection and calling helplines. Compulsive, often ritualised acts, like superstitious ones, can have an effect that is both soothing and preventative. In the burgeoning manuals of mental illness, the obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) from which he suffers is the one that most resembles religious practice. Finding a cure, whether druggy or talk-based, is an elusive business, but some symptom management is possible. Cognitive behavioural therapy has helped him. He hopes that his book and the survey of treatments it includes will also help others.

In Black Rainbow Rachel Kelly, a self-confessedly “ambitious” journalist, falls into a post-natal depression after the birth of her second child. The condition recurs, not after the next birth, but later, when she has twins. The first manifestation of the illness is anxious insomnia. With a three-month-old baby and a toddler to care for, she is exhausted, but feels secure in her happiness. So she can make no sense of the sudden breakdown that takes her into a howling darkness in which death is her only wish. Her husband, who recently ran for parliament and on whose campaign she worked, has to take over the juggling of work and children while her mother tends to her.

Kelly is privileged. Her Harley Street psychiatrist visits her regularly at home. He prescribes tranquillisers and sleeping pills. When these don’t work, she goes into hospital for purportedly expert care. It does nothing to ease her pain—physical and mental—and she quickly talks her way out. Her psychiatrist now insists that she take the antidepressants she initially refused. She doesn’t realise that, in the short term at least, they will make her worse, not better.

Words, prayer and poetry—a love for which she shares with her constantly caring mother—very gradually come to her aid, as do the pills. She also gains some knowledge of her condition. Doctors have been alert to post-natal depression ever since Hippocrates mentioned, around 420 BC, a case of insomnia and severe restlessness in a woman who had given birth to twins. But Kelly is no adept of the history of psychiatry or the kinds of insights psychotherapy has supplied over the past century. Nor, at first, is she offered any talk therapy. Only slowly does she see that her perfectionism and cheerful avoidance of facing her condition have had anything to do with her stress.

Poetry becomes her preferred curative medium. Most of the poems she likes are short and they command attention through rhythm and rhyme. They also echo her experience. She is not alone in her parlous state. The recognition helps her through.

This reminder that literature can heal is a useful one. Indeed, attentiveness itself, as various experiments in “mindfulness” have shown, has therapeutic properties.

Scott Stossel’s My Age of Anxiety evokes how the author has been plagued by anxieties and phobias since he was a child, and admits that he was a twitchy bundle of fears and neuroses from the age of two. Stossel is an emetophobe, terrified of vomiting and vomit. He has other phobias: Enclosed and open spaces, heights, germs and cheese, as well as competitive (really just most social) situations. At high school he was a relatively talented athlete but gave up competing for fear either of winning or of losing. At his wedding, he was drenched in sweat and swooned and shook to the edge of collapse. He also panics at the thought of public speaking, though he does undertake rather a lot of it. If this sounds a little like a Woody Allen syndrome, that is because Stossel is witty, an uncommon characteristic in the world of writing about mental suffering.

Yet his condition is real enough. Now in his early forties, he has been on a psychiatric and psychotherapeutic odyssey in search of a cure since the age of ten. He’s tried three decades of individual psychotherapy, family therapy, group therapy, rational emotive therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, hypnosis, meditation, role-playing and a few others—not to mention prayer, acupuncture and yoga. Usually he undertook several of these at the same time.

He has also been prescribed and has taken enough medication to write a dictionary of psychiatry. Thorazine, Imipramine, Valium, Librium, Ativan, Nardil, Prozac, Celexa, Zoloft, Paxil—the list goes on and on through the generations of sedatives, tricyclics and SSRIs. And he drinks enough to make Hemingway sound like a wimp. Beer, wine, gin, bourbon, vodka, Scotch, taken in precise volumes with various pills, can make flying possible and obscure his existential dread, which is the philosopher’s diagnosis of his condition. Yet none of this has cured his anxiety, though some combinations have worked temporarily.

Did I remember to mention that, on top of all this, Stossel edits the Atlantic, one of the best and the most venerable of America’s cultural magazines, that published Mark Twain and, of course, Henry James, whose Portrait of a Lady was first serialised in its pages?

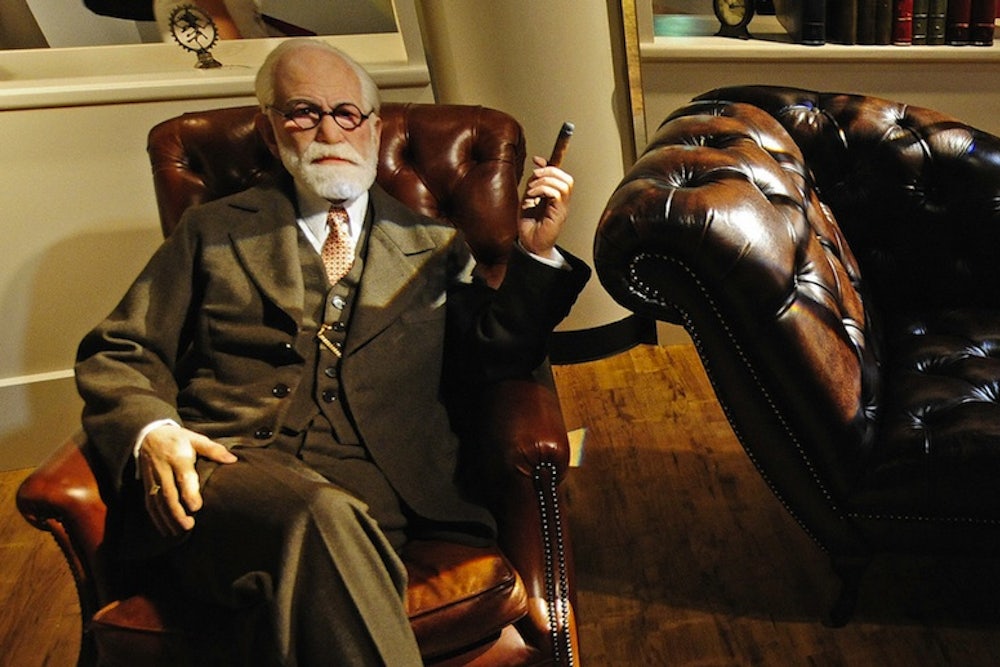

Henry James, like his brother William, suffered from various psychological ills, including what we would now call depression. William was also an influential player in the turn-of-the-19th-century moment that was so important in characterising many aspects of the modern mind sciences, from Emil Kraepelin’s psychiatric classifications and Sigmund Freud’s invention of psychoanalysis—that halfway house between philosophy and the more medicalised psychiatry—to the new psychology that William pursued. But neither of the otherwise prolific Jameses wrote in what is now a burgeoning literary subgenre: The memoir of mental illness, a form that arguably took off in the 1990s with William Styron’s masterly Darkness Visible and Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation. This took on girth in 2001 with The Noonday Demon by Andrew Solomon, and in the UK this year it achieved literary weight with Barbara Taylor’s The Last Asylum.

Memoirs of mental illness have helped to promote understanding of and to destigmatise the terrible disorders of the mind and emotions. But inevitably, like the roll-call of medications these memoirs often describe, they have also had some side effects. Human beings are suggestible creatures and it can be all too easy to package our suffering into ready-made disorders, check them out on a host of websites and diagnostic tick lists, and take them to the GP for prescriptions.

Way back in 1977 the prescient French philosopher/historian Michel Foucault pointed out that in our societies, “the child is more individualised than the adult, the patient more than the healthy man, the madman and the delinquent more than the normal and the non-delinquent.” Whatever our concurrent desire for a painless sanity, normality or, as it is now known, neuro-typicality, having a “secret madness” can help constitute what makes us individual. This may be one of the clues to the alarming rise of mental illness in recent decades.

Foucault might not have been surprised that the biggest success story in the pharmaceutical world since the advent of antibiotics has been the growth of antidepressants in the form of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—those much-hailed little pills that helped to bring about the very illness for which they are the touted cure. After a rocky start and unsuccessful clinical trials, SSRIs took off in the 1990s. By 2002 about 25 million Americans were taking them. Now, although they have been exposed as no more effective than placebos, the figure is closer to 40 million. The situation is no different in the UK, where one in four of us will, it is said, succumb to depression and anxiety at least once in our lifetime—though the more usual pattern is for these to become chronic conditions.

In the west we live in a time when we look to medics (rather than, say, politicians, priests, artists or philosophers) for solutions to most of our life and death problems. It is clear that the NHS in Britain and the rise of scientific medicine in the west count among the greatest achievements of the postwar years. But can doctors really be the providers of all our goods? Do they have the wherewithal to direct the mind and the emotions, do they hold the keys to sex, reproduction and death, besides healing our diseases?

Because it leads to such reflections, Stossel’s book is more engrossing than Adam’s and Kelly’s. It feels a tad churlish to judge books that are built on the experience of personal pain, but My Age of Anxiety is more capacious than merely one person’s experience. It offers a knowledgeable journey, based on Stossel’s individual trajectory, into the history of psychiatry and its diagnostic categories, from Kraepelin to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the DSM—the current, though increasingly contested, bible of the psychiatric professions.

David Adam, whose condition may be less tractable, covers a little of this but is less sure-footed. Stossel also provides a wise and unblinkered assessment of Freud’s views on anxiety and engages with the whole psychoanalytic and psychotherapeutic project. He has been to all sorts of “healers” and has done a lot of homework and thinking. Moreover, he understands brain chemistry and the latest neuroscience and writes about them with ease and brio.

His exploration of the nature versus nurture debate is particularly bracing. Stossel is unwilling to provide easy answers. He moves from Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy of 1621 to Darwin, to John Bowlby and his ideas about parenting, to the latest work on the FKBP5 gene (which seems to be linked to high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder) and the “warrior/worrier” COMT gene. His own great-grandfather, a dean at Harvard whose late-developing anxiety and depression took him in and out of mental health institutions over the last 30 years of his life, plays a part, too.

Is it heredity that has doomed Stossel to suffer from chronic anxiety from an early age? Does our genetic make-up predispose us to what used to be called the nervous ailments, even though these may be environmentally triggered? Is it, in Bowlby’s language, an insecure maternal attachment style and nervous parenting that catapult the child into anxiety? Or, in Freud’s resonant phrase, is “missing someone who is loved and longed for ... the key to an understanding of anxiety”?

Stossel likes to complicate the picture. This is as it should be, because human beings with language, history and society, as well as bodies, are hardly simple creatures plummeted into despair by a single direct cause. Nor, indeed, are they altogether susceptible to single, magic-bullet cures. The old nerve doctors—from George Cheyne in 18th-century England to George Beard, prophet of neurasthenia in late-19th-century America—suspected that it was the most sensitive and “civilised” people who suffered most from these kinds of ills. Today, according to a World Health Organisation survey of 18 countries, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness on earth. In Britain, four times as many people were treated for anxiety in 2011 as in 2007. According to the psychologist Robert Leahy, whom Stossel cites, every generation in the US since the war has been more anxious than the last—despite relative peace and prosperity.

Stossel is fond of Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, that philosophical reflection on anxiety and despair. He nudges the reader into considering that depression and anxiety may be less of an illness like, for instance, diabetes, and more of an existential condition. Nor does he shun the wider social factors that play on our inner states of being. Shaky economies, hyperbolic threat-mongering by the media and politicians, a climate of uncertainty, all inevitably affect levels of anxiety. So, too, does a society of many freedoms. Social mobility rather than strict hierarchy, envy rather than satisfaction, do not make for peace of mind. Nor does the illusion that our choices can always be rational and will bring us what we think we want. Desire and satisfaction don’t always lie where we think we’ll find them.

Faced by all this, a proportion will take flight into illness, which, after all, has some secondary benefits. One of these may be the writing of absorbing books in which the authors struggle against great odds to bring us news of the extreme conditions which are theirs. They have been to hell, yet they have married, have had children and led successful professional lives, and they have lived to tell the tale.

This article was originally published in Newstatesman.com.