The Children Act

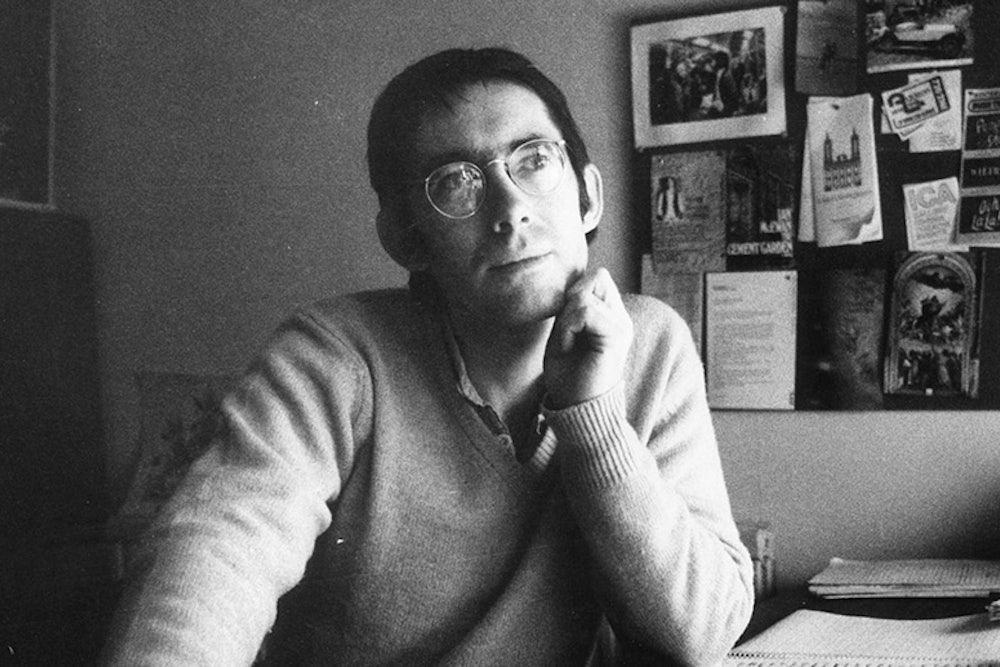

Ian McEwan

Jonathan Cape, 224pp, £16.99

The Zone of Interest

Martin Amis

Jonathan Cape, 311pp, £18.99

An author in his book must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.

Flaubert’s prescription, set down in 1852, was never one likely to be followed by Martin Amis, the guy who said he didn’t want to “write a sentence that any guy could have written,” or his contemporary Ian McEwan, who from his earliest stories kept in such close contact with his benighted characters that you could virtually smell his breath on the page. Over the years, the desire to editorialise has proved increasingly hard to resist, with Amis engaging in lofty allocutions on human nature, many of them borrowed from his essays and memoirs (“It’s the death of others that kills you in the end”—Experience in 2000 and The Pregnant Widow in 2010), and McEwan adopting a stealthier approach, superficially more dramatic and yet no less tailored to communicating his personal opinions—on science, mores, ethics.

The turning point came in 1987, with Amis’s story collection Einstein’s Monsters and McEwan’s novel The Child in Time, the first books that each writer published after making the transition from enfant terrible to proud father. For all the books’ differences, a number of shared concerns emerged. Sex, once either casual or squalid, had become something else entirely—cataclysmic, even cosmic. Violence was no longer a pay-off or punchline but a thing to walk in fear of. Also indicative were these words from McEwan: “I am indebted to the following authors and books . . .” And these ones from Amis: “May I take the opportunity to discharge—or acknowledge—some debts? . . . I am grateful to Jonathan Schell, for ideas and for imagery.” Bedtime reading on subjects such as nuclear weapons, quantum mechanics and the Second World War had been delivering the kinds of shocks and thrills that the authors had been aiming for with stories about boys and girls mistreating one another in decaying city bedrooms. It was time to chase a grander frisson.

What distinguishes this move from, say, the more recent fashion for the essay novel—see the work of W. G. Sebald, Geoff Dyer, Teju Cole, Laurent Binet—is that Amis and McEwan have tried to accommodate facts and arguments into a prose that resists being candidly discursive. Ideas about sexual politics (Amis’s The Pregnant Widow, McEwan’s On Chesil Beach), science v. superstition (McEwan’s Enduring Love and Saturday), the new physics (The Child in Time, Amis’s Night Train) and political violence (Amis’s Time’s Arrow, Black Dogs and House of Meetings) are put into characters’ mouths (mostly by Amis) or wedged into a narrative structure (mostly by McEwan). The novels in this period that seem freest from these vices—among them, McEwan’s Atonement and Amis’s Yellow Dog—are beset, to varying degrees, by other problems; in McEwan’s case, maniacal control and, in Amis’s, frivolity and self-plagiarism.

The desire to keep fiction and non-fiction as separate categories is most obviously reflected in Amis’s tendency to offer an essay to buttress or explain the ideas communicated in the fiction. The stories in Einstein’s Monsters were preceded by “Thinkability,” a kind of manifesto on the Bomb, while the 300 pages of his new novel, The Zone of Interest, are capped by a seven-page treatise, “Acknowledgments and Afterword: ‘That Which Happened.’” If the prose in novels by both Amis and McEwan seems to be creaking under the burden of researched fact and rehearsed message, only Amis goes out of his way to confirm the suspicion.

There was a time when the writers’ impulses flowed in the opposite direction, in resistance to worldliness. (Borges was a love they shared.) Amis’s second novel, Dead Babies, came with a brief note in which he declared: “I don’t know much about science, but I know what I like.” McEwan’s second novel,The Comfort of Strangers, studiously avoided naming its setting as Venice. The Zone of Interest, by contrast, deals with Zyklon B, while McEwan’s new novel, The Children Act—a noted omission from this year’s Man Booker Prize longlist—begins with the word “London” and contains numerous itineraries as wellas various news bulletins.

The character zipping around the city, on foot and by cab, and pondering the crises of 2012—the Leveson inquiry, the Arab spring—is Fiona Maye, a high court judge who works in the family division. Her latest case involves a 17-year-old Jehovah’s Witness who is refusing a blood transfusion on theological grounds. It seems to be a straightforward situation, both legally and ethically. The view of Jehovah’s Witnesses “lay far outside those of a modern, reasonable parent,” Fiona tells herself, having earlier reflected that “she brought reasonableness to hopeless situations.” Whereas religion is at once unreasonable and unkind, the law—which Fiona “belonged to . . . as some women had once been brides of Christ”—manages both to be right and to do the right thing. Clearly she is riding for a fall—if not a public humbling, then a shock to her value system. The words “kind” and “reasonable” recur throughout the novel and prove themselves unstable.

As a writer, McEwan is open to all sorts of charges but underplaying his characters’ occupations isn’t among them. In his handling, Fiona is less a lawyer—day in, day out—than a vehicle for exploring the quandaries thrown up by her profession:

Religions, moral systems, her own included, were like peaks in a dense mountain range seen from a great distance, none obviously higher, more important, truer than another. What was to judge?

While the case unfolds, Fiona’s husband, Jack, a geologist—geology being an old foe of religious faith—is having an affair with an offstage character who is described only as a “28-year-old statistician.” This prompts Fiona to wonder, “Who was her protective judge?” Throughout the book, her status as an independent consciousness is subservient to the broader resonances of her story. At times, her interior monologue can sound detached to the point of blurbism: “Here was a matter of life and death”; “This, Fiona decides as her taxi halted in heavy traffic on Waterloo Bridge, was either about a woman on the edge of a crack-up making a sentimental error of professional judgement, or it was about a boy delivered from or into the beliefs of his sect by the intimate intervention of the secular court.”

By this point, after Amsterdam and Atonement and Solar and Sweet Tooth, McEwan has taken his readers off guard so many times that the only way to do it again is to lull them into a false sense of insecurity and then follow the original script. That is roughly what happens here. The Children Act is distinguished from McEwan’s previous books in executing an argument about rival world-views that doesn’t facilitate a charged and twisting narrative. It is a sign of his growing confidence as an allegorist that he gets the job done so quickly.

But where’s the joy? Of McEwan’s central addictions (thematic signposts and thriller mechanics), the latter was always the more endearing. In the new novel, the details have lost their sinister charge but retain a symbolic burden. We first see Fiona at home in London, not far from Gray’s Inn, surrounded by the comforts of middle-class, secular life, all of them somehow tainted: her “tiny Renoir lithograph” is “probably a fake”; a “blue vase” has long been empty; the fireplace hasn’t been “lit in a year”. Enduring Love and Saturday both pitched science, as represented by a science journalist and a surgeon, against irrationality, as represented by violent sufferers from de Clérambault’s syndrome and Huntington’s disease—even though in both cases poetry, a product of intuition, was shown to offer something that reason and reasoning couldn’t. The Children Act presents a scenario in which the virtues of the secular life, poetry included, fight against the consolations of religious belief and no winner is declared. All the things that Fiona lives by—most importantly, music and the law—are found in some way wanting. It may be a different, more supple and surprising argument but it is an argument nonetheless.

The Children Act is pretty squarely about kindness; The Zone of Interest takes a similar approach to courage. Though the word “Auschwitz” isn’t used until the afterword, the novel’s setting is a death camp in Poland, where the handsome functionary Golo Thomsen falls head over heels for Hannah Doll, the wife of the camp’s commandant, but soon finds himself investigating the fate of her former lover—a rare opportunity for this reluctant Nazi (“The Jews had to come down from their high horse . . . But this – this is fucking ridiculous”) to remind himself of the kind of man he could be.

Amis doesn’t get much chance to explore this promising moral drama because he is too busy telling us things about the Second World War and the Third Reich or, more often, having his characters tell them to each other: “Rubber—it’s like ball bearings. You can’t make war without it”; “How do you pacify Siberia? Which is the size of eight Europes ...” Golo, who shares narrating duties with Paul Doll, is especially helpful: “The Sorrows of Young Werther, the Goethe novella so beguilingly forlorn that it provoked an avalanche of suicides . . .”; “that profoundly un-German contraption, ‘democracy’ . . .”

You can often hear Amis passing on some unexpected insight he learned from Martin Gilbert or Richard J. Evans or one of the dozen other historians he thanks: “Now here’s a common fallacy I want to knock on the head without further ado: the notion that the Schutzstaffel, the Praetorian Guard of the Reich, is predominantly made up of men from the Proletariat and the Kleinburgertum.”

Amis’s tendency to use German terminology, annoying in itself, is juxtaposed with the use elsewhere of German spelling as a source of humour: “the brambles of her Busch . . . the great oscillating hemispheres of her Arsch.” On the whole, Nazism is ridiculed, rather than plumbed. Two scenes hinge on Paul Doll acclaiming the logic of poorly argued bits of Mein Kampf.

In the past quarter-century, Amis and McEwan, at one point the most dynamic and distinctive of English writers, have become at once more cerebral and more self-consciously literary. If physicists and historians have captured their brains, then earlier male writers have overtaken their prose styles. Discharging his debts in Einstein’s Monsters, Amis mentioned not only Jonathan Schell—for his books about nuclear annihilation—but Saul Bellow, J. G. Ballard, Kafka, Nabokov, Borges and Rushdie. In Time’s Arrow, he acknowledged Isaac Bashevis Singer and Kurt Vonnegut, from whom he borrowed the book’s backwards structure.

McEwan’s Saturday announced its intentions with a long epigraph from Bellow’s Herzog and Solar did the same with a shorter one from John Updike’s Rabbit Is Rich, while On Chesil Beach kicked off with an expression of resignation borrowed from Philip Roth’s American Pastoral (“But it is never easy”). In McEwan’s new novel, that opening “London” is followed by: “Trinity term one week old. Implacable June weather. Fiona Maye . . . at home on Sunday evening . . .” It’s an allusion to an earlier courtroom novel, Bleak House: “London. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather.”

Nabokov has proved a stubborn presence, detectable once or twice in The Children Act (in the use of parentheses, for example, and in a description of baldness) and on every page of The Zone of Interest. Both Paul and Golo speak in the voice of Humbert Humbert, describing actions (Paul Doll) or looks (Golo) in would-be epic terms. The Nabokov influence is also felt in the book’s onslaught of exotic words and phrases—“incarcerationary”, “bemedalled”, “crepitated”, “plebiscitary acclamation”—and in the sort of clever coldness that inspires phrases such as “the autobahn to autocracy.” People are “gravid” (rather than heavy) with emotion and unable to keep “countenance” (rather than face). Even the genuinely pitiable Szmul, a Jew forced to help at the camp, falls victim to Amis’s version of Nabokov-like grandiloquence, with its taste for the sonorous repetition: “I feel like a man with prosthetic hands – a man with false hands.”

After a while, the mixture of the learned and the knowing kills all hope of a meaningful connection between Amis and his characters—with an effect on the reader that is alienating when it isn’t repellent.

This article originally appeared in the New Statesman.