An official State Department photo of the September 11 meeting in Jeddah between Secretary of State John Kerry and King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, posted on Flickr, could be a metaphor for the current state of U.S.-Saudi relations. It is out of focus.

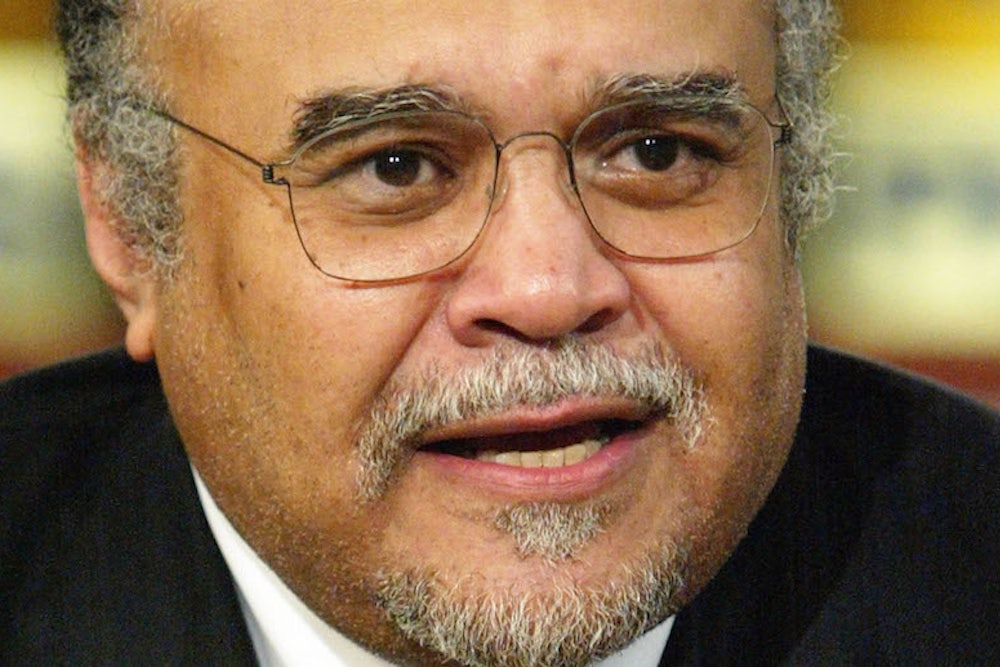

Why such a photo was chosen for Flickr, along with a single (in-focus) close-up of Kerry and the Saudi monarch, can only be a matter of speculation. One obvious possibility is that the U.S. side was upset with the attendance—indeed, the prominence—on the Saudi side of Prince Bandar bin Sultan, one-time long-serving ambassador to the United States, later head of Saudi intelligence, now adviser and special envoy to the king as well as secretary-general of the Saudi National Security Council (NSC). A fuzzy photo might have served to downplay his involvement.

Bandar fell out with the Obama Administration in 2012-2014 over the question of support for opposition fighters in Syria whom he wanted to back enthusiastically despite U.S. objections. Because of this, the White House came to view him as out of control and refused to work with him. Eventually, in April of this year, clearly responding to U.S. pressure, the king sacked him as intelligence chief but allowed him to keep his nebulous Saudi NSC role. Three months later, Bandar was back in favor in Riyadh, taking a special envoy role and has been seen at several top-level meetings since.

Saudi Arabia regards itself as the leader of the Muslim world, and as such sees itself as existing in an existential struggle with Iran for dominance of this world. The centuries old Sunni/Shiite divide, which has opened up dangerously since the 1979 Iranian revolution, is compounded by the political Islam of the Brotherhood, which views Arab monarchies such as the House of Saud as anachronisms at best but, more dangerously, un-Islamic.

For its part, Washington's principal interest in Saudi Arabia is safeguarding its role as the world's largest exporter of oil, with subsidiary interests of allowing Saudi Arabia to use market leverage to keep prices stable and not too high. This policy approach—which prompted U.S. military involvement after Saddam Hussein's 1990 invasion of Kuwait and explains the continuing naval and air force commitments in the Gulf area, though Saudi Arabia does not host any U.S. bases—tolerates (for the most part) often extraordinary behavior by the Saudis in their attempts to preserve what they regard as their Islamic pre-eminence. Certainly in the past this has included support for terrorism. A particularly outrageous example of this: From about 1996 to around 2003, Defense Minister Prince Sultan and Interior Minister Prince Nayef paid off Osama bin Laden so al Qaeda would not target the kingdom.1

Today, the Saudis deny any support for terrorists and, indeed, have made it a criminal offense for its citizens to fight in Syria or to provide support for opposition fighters. But this is at odds with decades of Saudi practice, sending religious youth to fight in Afghanistan, Chechnya, Bosnia, and elsewhere. It is also not the way Bandar spoke of his instructions from King Abdullah when he was appointed intelligence chief: he stated that he was charged with getting rid of Bashar al Assad, containing Hezbollah in Lebanon, and cutting off the head of the snake (Iran). For emphasis of Saudi sincerity of purpose in Syria, he said that he would follow his monarch's instructions, even if it meant hiring "every SOB jihadist" he could find.

In policy circles in Washington, there is a common wisdom that Saudi support for fighters in Syria has not included al Qaeda types—though it's pretty obvious that Qatar, the kingdom's small neighbor but big diplomatic competitor has been supporting fighters of an al Qaeda affiliate (Jabhat al-Nusra). In reality, the spectrum of opposition fighters—from President Obama's "teachers and pharmacists" through to IS, ISIS, ISIL (call it what you will)—is full of muddy distinctions. This could explain why Jordan, sandwiched between Saudi Arabia and Syria, declined to allow Bandar to set up training camps for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of opposition fighters. Jihadi types might influence disaffected Jordanian youth and would certainly annoy Assad, who could orchestrate a refugee crisis that might overwhelm Jordan. King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia was evidently so annoyed at the veto that he cut off all aid to cash-strapped Jordan this year, which had been running at $1 billion annually.

Despite the diplomacy of recent days, which suggests an emerging coalition that includes Saudi Arabia and will take on the fighters of the Islamic State in Iraq and perhaps Syria, the House of Saud will likely continue to try to balance the threat of the head-chopping jihadists, while also trying to deliver a strategic setback to Iran by overthrowing the regime in Damascus. From a Saudi point of view, the move of IS forces into Iraq contributed the removal of Nouri al-Maliki in Baghdad, who they regarded as a stooge of Tehran. Despite official support by Riyadh for the new Baghdad government, many Saudis who despise Shiites probably regard IS as doing God's work.

As with the then-nascent threat of al-Qaeda in the late 1990s, Saudi Arabia's view of self-preservation now (both toward the Islamic State and the looming prospect of a nuclear Iran) will probably involve policy hypocrisy toward Washington. From the Saudi point of view, there is exasperation with the caution of President Obama. The announcement that retired Marine General John Allen will be a Presidential Envoy on Iraq and Syria, with a State Department deputy, will likely sound to the House of Saud and other Gulf monarchies as merely being "shoes on the ground" rather than even limited "boots on the ground." At the very least, the Saudis are going to be reticent in their cooperation. At worst they will define their self-interest narrowly and not care if it undermines the U.S.

Both men are now dead. The claim was first made in a January 9, 2002, U.S. News and World Report story, without naming the princes. But I identified them and gave them mention twice in op-eds I wrote for the Wall Street Journal. For pedants who wonder why this detail never made it into the report of the September 11 Commission, it could be that (other than the staff of the Commission not reading the Wall Street Journal) the foreign intelligence agency which tracked the transfers did not give permission for the information to be made public, a necessary protocol of spy agency exchanges.