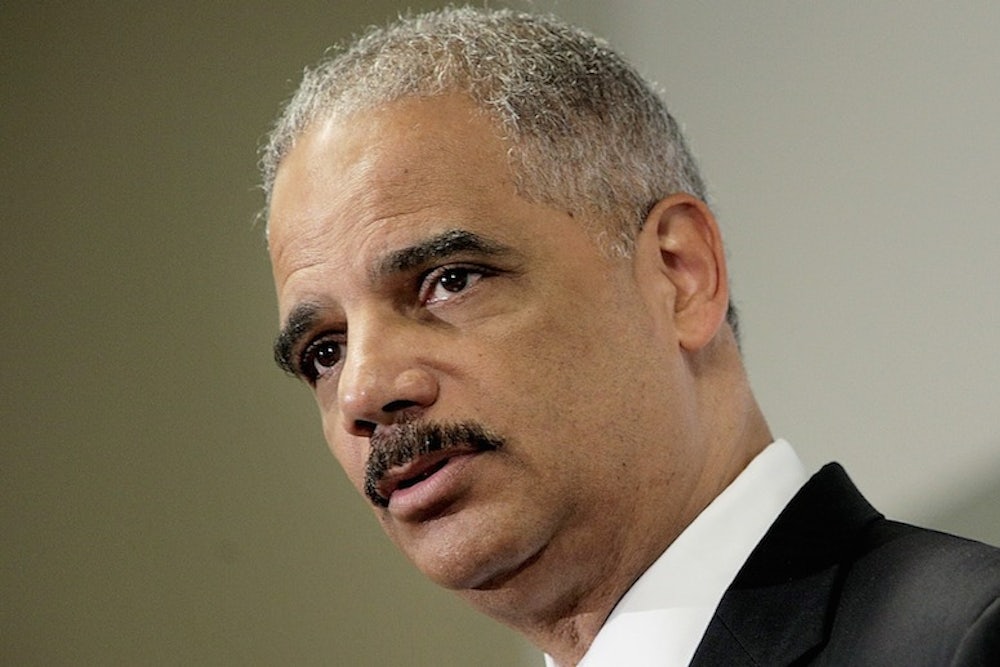

On September 25, Attorney General Eric Holder announced his resignation. He made history as the nation’s first African American attorney general and will most likely be remembered for his vigorous enforcement of the nation’s civil rights laws. He deserves equal accolades for his leadership in working to reform the nation’s broken criminal justice system. Since his appointment as attorney general, he has consistently criticized the draconian federal sentencing laws that require lengthy mandatory minimum sentences in nonviolent drug cases and has decried the unwarranted racial disparities in the criminal justice system, calling the phenomenon “a civil rights issue … that I’m determined to confront as long as I’m attorney general." And he certainly kept that promise.

Before becoming the nation's top law enforcement officer, there was no indication that Eric Holder would ultimately become an advocate for poor people incarcerated in our nation’s prisons and jails. After all, Eric Holder spent most of his professional career as a criminal prosecutor. He started out as a prosecutor in the Justice Department’s Public Integrity Section where for 12 years he worked to put away corrupt public officials. During his five years as a judge in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia, he earned a reputation as a tough sentencer, locking up countless young African American men for long periods of time.

Eric Holder left the bench to become the first African American United States Attorney for the District of Columbia. When Holder was appointed to be D.C.’s chief prosecutor, I was the city’s chief defender. As Director of the Public Defender for the District of Columbia, my interactions with Holder’s predecessors were very adversarial. Holder was determined to change that. Soon after his appointment, he visited my office and promised a change in policies and practices. Although he instituted a number of programs in his office, he did not make efforts to reduce the prison population or address racial disparities. He was more polite than his predecessors, but there was absolutely no indication that he would ultimately lead the charge to reverse the nation's shameful record of incarcerating more of its citizens than any western nation in the world.

In 1997, Holder continued his career as a prosecutor when he became the nation’s first African American deputy attorney general under Janet Reno during the Clinton administration. As second in charge at the Justice Department, Holder supported and championed Reno’s positions on criminal justice issues. At that time, sentencing laws required judges to sentence those in possession of five grams of crack cocaine to a mandatory minimum of five years in prison while that harsh sentence could only be imposed in cases involving powder cocaine when the amount was 500 grams. The enforcement of these laws resulted in much harsher sentences for African Americans. Although Reno was in favor of narrowing the disparity, she strongly opposed eliminating it, and, as her deputy, so did Holder.

At the end of Clinton’s second term, Holder went into private practice before returning to lead the Justice Department that he’d worked in for most of his career. From the beginning of his term as attorney general in 2009, Eric Holder began to champion vigorous reform of the criminal justice system. The vast majority of criminal cases are prosecuted in state courts, and the Attorney General has no supervisory power over state and local cases. However, Holder consistently used his bully pulpit to advocate for criminal justice reform and took direct action to order reforms in the federal system throughout his tenure as attorney general.

As early as June 2009, Holder spoke at a symposium on reforming federal sentencing policy sponsored by the Congressional Black Caucus. In his remarks, Holder announced that he had ordered a review of the department’s charging and sentencing policies, consideration of alternatives to incarceration, and an examination of other unwarranted disparities in federal sentencing. He stated that “the disparity between crack and powder cocaine must be eliminated and must be addressed by this congress this year.”

The following year, Holder gave remarks at the Justice Department’s National Symposium on Indigent Defense, where he spoke passionately about how the Sixth Amendment right to counsel was not being fulfilled for poor people charged with crimes. He pledged his commitment to improving indigent defense, stating that he had “asked the entire Department of Justice ... to focus on indigent defense issues with a sense of urgency and a commitment to developing and implementing the solutions we need.” And he fulfilled that pledge. In October 2013, the Justice Department awarded a total of $6.7 million to state and local criminal and civil legal services organizations that provide defense serves for the poor. Most recently, Holder filed a statement of interest expressing his support for a lawsuit against the state of New York that challenges the deficiencies in New York’s public defender system.

Holder’s most comprehensive criminal justice reform efforts were announced in a speech he gave at the American Bar Association’s Annual meeting in 2013. In these remarks, Holder said, “Too many people go to too many prisons for far too long and for no truly good law-enforcement reason.” He also decried the unwarranted racial disparities, stating that “people of color often face harsher punishments than their peers. ... [b]lack male offenders have received sentences nearly 20 percent longer than those imposed on white males convicted of similar crimes. This isn’t just unacceptable—it is shameful.” Holder then went on to announce sweeping reforms, including ordering federal prosecutors to refrain from charging low level nonviolent drug offenders with offenses that impose harsh mandatory minimum sentences; a compassionate release program to consider the release of nonviolent, elderly, and/or ill prisoners; the increased use of alternatives to incarceration; and the review and reconsideration of statutes and regulations that impose harsh collateral consequences (such as loss of housing and employment) on people with criminal convictions.

We have yet to witness the positive effects of Holder’s criminal justice legacy, and some may suggest that he didn’t go far enough. But few will disagree that his efforts surpass those of any previous attorney general. Did Holder’s views on criminal justice evolve over time? Or did he always believe that the system was broken and in need of reform? Perhaps both statements are true. What matters is that at the end of the day, when he was in a position to effect meaningful change in our criminal justice system, this former prosecutor became a champion of liberty. And for that, this former public defender will forever be grateful.