I was a poor intern. In 2012 I worked for four weeks1 at the New Statesman’s former offices near Blackfriars Bridge. Every day I would leave a little early and walk across the river to my evening job—serving overpriced cocktails in a theatre bar. It was exhausting. Most weeks I didn’t work Sundays—I did laundry, what joy—but some weeks I worked the afternoon matinee because I was skint and the theatre paid double time, meaning I had worked every day of the week. My friends all told me how lucky I was.

One evening in the middle of winter I was walking over Blackfriars Bridge when a black shadow flashed in front of my eyes. I looked up and saw a horrified woman looking in my direction.

“Did someone just jump off the bridge?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

We both peered over the edge. Maybe the jumper was an intern, I thought, watching a man around my age bobbing in the water. It’s a tough life. (A police boat pulled him out less than a minute later—he appeared, at least physically, intact).

It’s always been tough. In The Physiology of the Employee (1841)—a pamphlet-length essay on the misery of bureaucracy—the French novelist Honoré de Balzac wrote: “An intern is to the Civil Service what a choirboy is to the Church, or what an army child is to his Regiment, or what rats and sidekicks are to Theatres: innocent, gullible, and blinded by illusions.”

It was a world he knew well: a world of endless copying, traduced ambition, and waste. After graduating from the Sorbonne, Balzac interned at a Paris law firm. He spent three years “training” under Victor Passez—a family friend—but quit in 1819, cranky, depressed, with the intention of becoming a writer (Balzac never tired of poorly conceived get-rich-quick schemes—he attempted to set up a publishing company and wanted to grow pineapples in vast greenhouses to export en masse).

The Physiology begins by criticising a society “that no longer believes in anything but money and exists only by virtue of its penal code and taxation laws.” André Naffis-Sahely, who has just translated the essay for the New York-based Wakefield Press, ties Balzac’s essay to one of the most pressing questions of our own time:

On leaving college, my generation feels deprived of choice, thinking they must either enter the rat race right away or wither on the vine. That’s what they’re told by the media and just about everyone else. Many “choose” any career available simply in the hope of achieving some security, such as a house. Unfortunately, we are also in the midst of a housing crisis. Without parental largesse or some sort of inheritance, our wages simply aren’t enough to get our feet on the housing ladder, and as houses were once the only capital the lower or middle classes could ever be certain of acquiring, this poses quite a straightforward problem: If you’re not among the privileged few with so-called dream jobs, where you gladly work for next to nothing because you feel fulfilled, why should we work?

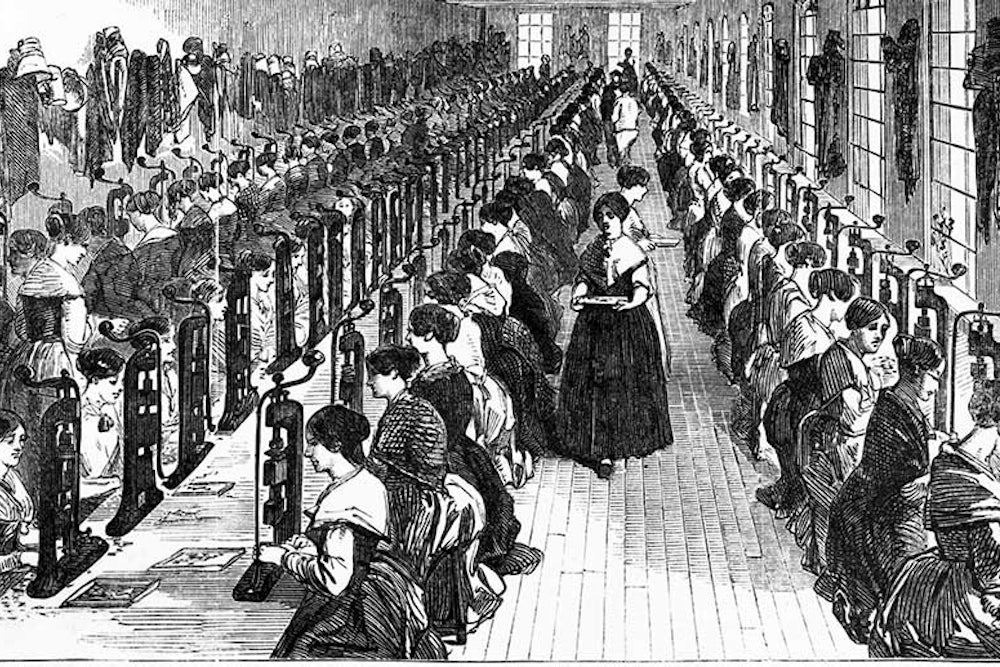

Balzac defined an employee as “someone who needs his salary to live and isn’t free to resign as he isn’t equipped for anything other than endless piles of paperwork.” The grand bureaucratic institutions of the modern world—accountancy, government, law, finance, tech—generate fear among their employees, gradually distorting their view of themselves and those around them, breeding insecurity and rewarding the creation of pointless work.

After graduating from university the dandy poet Baudelaire wrote: “At school I read, I cried, sometimes I fell into a rage, but at least I was alive, which is more than I am now.” Balzac’s fiction is dedicated to exploring this transformation—he was born in the era of the Napoleonic Code, which aimed to make France’s bureaucratic institutions transparent, meritocratic and streamlined, but ended up making them worse—laying the groundwork for Kafka, Sloan Wilson, and The Wire in the years to come. It all begins, as Balzac explains below in an excerpt from Naffis-Sahely’s new translation of The Physiology, with those persistent, “stubborn youths,” the interns:

Chapter VII: The Intern

An intern is to the Civil Service what a choirboy is to the Church, or what an army child is to his Regiment, or what rats and sidekicks are to Theatres: innocent, gullible, and blinded by illusions. Where will we go without illusions? Illusions are what give us the strength to scrape a living from the arts, to devour all the basics of scientific knowledge, while still giving us something to believe. Illusions give rise to inordinate faith! Now the intern believes in bureaucracy; he doesn’t think it to be as frigid, harsh, and atrocious as it actually is.

There are two types of interns: poor ones and rich ones.

The poor intern has pockets full of hope and needs a permanent position; the rich intern is unmotivated and wants for nothing. After all, a wealthy family wouldn’t be stupid enough to send their intelligent son off to the Civil Service.

The rich intern is entrusted to the supervision of a senior employee or placed next to the Office Manager, who initiates him into what Bilboquet, that profound philosopher, has called the high comedy of the Civil Service. They soften the horrors of the probation period until a suitable position has been found for him. The rich intern is never a source of worry in the office. The employees know that he poses no threat, as the rich intern always sets his sights on the highest positions. The Press often persecutes the rich intern, because he will invariably be a cousin, nephew or relative of some deputy of the Chamber or influential peer; but the employees are his accomplices and are always seeking his protection!

Thus, only the poor intern is the real intern. He almost always follows in his father’s footsteps, being the son of an old employee’s widow, or of a retired civil servant who lives off a meagre pension; his family starves itself to keep him fed, clean, and clothed. He nearly always lives in a neighborhood where the rents are low, and he leaves for work early in the morning. The morning skies are the only Eastern Question he cares about! He’s plagued by so many worries: getting to work on foot while avoiding all the muck, ensuring his wardrobe is kept in good condition, and calculating how much time he might lose if a sudden rain-shower forces him to seek shelter! Paved sidewalks and the cobbled quays and boulevards were a real blessing for him. If, for some bizarre reason, you happen to be walking about Paris at seven-thirty in the morning, and you should happen to spot a timid-looking young man without a cigar in his mouth striding through the biting cold, rain, and all sorts of horrible weather, just tell yourself: “There’s an intern!” He’s already eaten. If you pay close attention to his pockets, you’ll notice the outline of a baguette that his mother gave him to bridge the nine-hour gap between breakfast and dinner to avoid ruining his stomach.

The intern’s innocence doesn't last very long. He soon realizes the gulf that exists between him and the Assistant Manager, an estimate that eluded the grasp of mathematicians like Newton, Pascal, Leibniz, Kepler, or Laplace, which roughly amounts to the difference between 0 and 1 or between a problem and its solution!

The intern fully grasps the impossible hurdles that constitute a career, he understands when other employees talk about “preferential treatment” and explain it to him, he uncovers office intrigues, and he sees the exceptional means whereby his superiors rose to the top of the ladder: one of them married a girl who’d made a grave mistake; another married a minister’s illegitimate daughter. But the intern, a highly talented individual, takes his responsibilities seriously and risks his health by performing forced labor with the blind perseverance of the mole: Do the rest of us always feel capable of such remarkable feats?

Office walls have eyes and ears.

Incompetent men tend to have very clever wives who dragged them to where they got, or got them elected as deputies of the Chamber. If he’s unsuited to office politics, he starts dabbling in petty intrigue in the Chamber. One of these men is married to a woman who’s also the mistress of an influential statesman; another keeps a powerful journalist in his pay.

Disgusted with this state of affairs, the intern resigns. Three-quarters of all interns quit the Civil Service before ever being officially employed. The ones left behind tend to be either stubborn youths or cretins who tell themselves: “I’ve been here for three years, I’ll definitely get a job,” or young people who think they’ve found their true calling.

As far as the Civil Service is concerned, being an intern is clearly like being a novice in a religious order: It’s a trial period. The ordeals they are subjected to are rather harsh: One quickly sees who can cope with hunger, thirst, and poverty without being crushed by it, and how hard they can work without experiencing self-disgust, thereby proving they have the appropriate temperament to endure such a horrible existence, which can also be described as the “office sickness,” over the course of their lives.

From this point of view, interns are not the victims of a despicable trick whereby a government can get people to work for free, but rather are the beneficiaries of charity. On average, only seven out of thirty interns ever acclimatize to the office environment, having trained their hand to constant scribbling, having learned to switch off their minds, or fence their souls within the tight confines of the Civil Service, so as to finally become either clerks or perennial managers-in-waiting.

The day they are hired is a fine occasion: they pocket their first month’s pay and don’t hand it all over to their mothers! Venus always smiles kindly on the first fruits from the ministerial coffers.

At the time the NS paid interns travel expenses—which in my case were zero because I walk everywhere. The magazine no longer accepts unpaid interns. All interns are provided for either through in-house bursaries or schemes paid for by charities including the Wellcome Trust and Social Mobility Foundation.

The Physiology of the Employee is out now (Wakefield Press)

This piece was originally published on newstatesman.com.