American readers who were caught flat-footed by the announcement that Patrick Modiano had won the Nobel Prize in Literature shouldn’t feel too guilty. At the time the prize was announced, exactly one book by Modiano was in print in English; he was as unknown in this country as J.M.G. Le Clezio, the previous French laureate, had been when he won the Nobel in 2008. Whether this is an indictment of our provincialism, or of the failure of the publishing industry to translate enough books, I’m not sure. After all, this is a country of 300 million people, almost as big as the entire European Union, and keeping up with American literature is surely a full-time job for most American readers.

Still, if there is one way to ensure that a European writer will finally be translated, the Nobel is it; and English versions of Modiano’s books are already on their way to bookstores. The first to arrive is Suspended Sentences, which Yale University Press was already scheduled to publish, but is now rushing into print thanks to the Nobel announcement. For almost all American readers curious about Modiano, it will be their first introduction to his work. What sort of writer does it reveal?

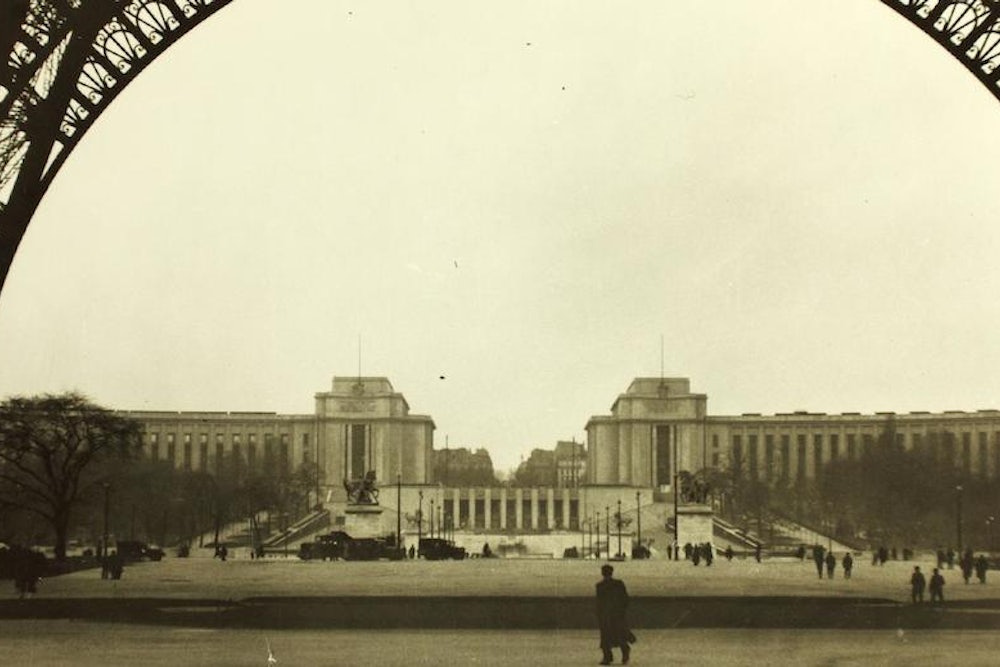

First of all, a dedicated Parisian. Of the three novellas that make up this short volume, two take place in Paris and one in the suburbs; and Modiano writes about the French capital with a possessive affection that feels almost erotic. The narrator—who is always a version of the author—thinks back to the Paris of his teenage years, in the 1960s (Modiano was born in 1945), as to a shadowy paradise lost. He dwells on the changes time has brought to the city—the destruction of a neighborhood to make way for a highway, the disappearance of old haunts and old friends. Like Walter Benjamin, who believed that a whole civilization could be conjured from scraps of the Parisian past, Modiano seizes on even the smallest scraps of history. In “Flowers of Ruin,” the third story in the book, he provides extracts from old phone books and lists all the businesses to be found on a certain street. Many of this novella’s short sections seem to begin with the evocation of a place, a street name, a landmark:

The Porte d’Italie marked the eastern border of that territory. Boulevard Kellermann led west, up to the Poterne des Peupliers. To the right, the SNECMA plant looked like a huge cargo ship run aground on the edge of the boulevard. … A bit farther on, to the left, was the Charlety stadium. Weeds grew through cracks in the concrete.

Because he is remembering a Paris of 50 years ago, even a reader intimately familiar with the city will feel a sense of estrangement here. For most American readers, such passages function almost as poesie pure, an incantation of exotic names. In his introduction to the book, the translator Mark Polizzotti notes the affinity of Modiano’s fiction with “the atmosphere of Marcel Carne’s fog-drenched films, Edith Piaf’s smoky laments, and Brassai’s nocturnal photographs.”

If this suggests that Modiano’s is a romantic Paris, however, it is misleading. For the stories that play out against this urban backdrop are unsettling, full of shadowy menace and secrets. In each of the three novellas—which were originally published between 1988 and 1993—the narrator looks back to events from his youth and childhood, and beyond that to things that happened before his birth, in the lives of his parents and their friends. The distinctive tone of these stories comes from the way these retrospective glances are blocked, fogged over by ignorance and the passage of time. The Modiano-figure is estranged from his own history: “Remembering that evening, I feel a need to latch onto those elusive silhouettes and capture them as if in a photograph. But after so many years, outlines become blurred, and a creeping, insidious doubt corrodes the faces. So many proofs and witnesses can disappear in thirty years.”

In the first story in the book, “Afterimage,” the enigmatic silhouette at the center of things belongs to one Francis Jansen, a photographer whom the narrator met in 1964, when he was 19 years old. Jansen is a man who seems to be trying to erase himself from the world. He never answers the door or the telephone, and when the eager young narrator takes an interest in his photographs, he disdains them: “I can’t stand to look at them anymore.” “Of all the punctuation marks, he told me, ellipses were his favorite,” Modiano writes, rather portentously. By the end of the story, Jansen has absconded for Mexico, without leaving a trace of himself behind. Years later, the narrator stalks the old locales where he knew Jansen, hoping to turn up some evidence to convince himself the man really existed. In the process, he feels his own identity starting to slip away: “It was over. I was nothing now. Soon I would slip out of this park toward a metro stop, then a train station and a port. When the gates closed, all that would remain of me would be the raincoat I’d been wearing, rolled into a ball on a bench.”

Why does Jansen feel such an urge to disappear, and why does the narrator sympathize with his alienation? The answer seems to be linked to the one concrete piece of biographical data we learn about Jansen: a Jew, he was detained at the Drancy internment camp during the Nazi Occupation of France, and only missed being deported to Auschwitz by a stroke of good luck. This situation recurs in the two other novellas, “Suspended Sentences” and “Flowers of Ruin,” only there the person who escapes Drancy is the narrator’s father—and indeed, Polizzotti’s introduction informs us, the same thing actually happened to Albert Modiano, the writer’s father.

This trauma, which took place not long before Patrick Modiano was born, feels like the historical key to these mystery-stories; it is the central enigma that turned him into a detective of his own past. In “Suspended Sentences,” the narrator recalls a year of his childhood when his parents more or less abandoned him and his younger brother to the care of a group of eccentrics—a young woman named Annie, her mother Mathilde, and their friend Little Helene, a former circus performer. As the narrator fills in the canvas of that year—the school, the abandoned chateau where he went to play, the occasional visits to Paris—the strangeness of the situation is only heightened. Why is the young boy peremptorily expelled from his school? Why don’t his parents come to retrieve him? Why does Annie disappear at night and then return with strange men in tow?

The answer, once again, turns out to be connected to the absent father, whose connections with a wartime black-marketeering group—the “Rue Lauriston gang”—may have saved his life. By the end of the story, we realize that the boy’s kindly guardians are actually criminals, and that underneath the placid surface of his life, something dreadful is being prepared. Still, what matters is less the facts about what is going on with the child’s guardians than the atmosphere of abandonment and bewilderment that Modiano summons. And that atmosphere lingers into the third tale, “Flowers of Ruin,” which braids the story of a pre-war murder mystery together with the narrator’s pursuit of another enigmatic man—Pacheco, who may or may not have been involved in that crime, and who also disappears without a trace, like Jansen, and like the narrator’s father.

These novellas were originally published separately, but the decision to group them together makes perfect sense. In mood and often in subject matter, they read like variations on a theme: the missing man, the absent parents, the ravages of time, keeping coming back under different names. In each tale, the narrator remains bewildered by history, his own and his family’s, trying to make a coherent narrative out of the fragments he inherited. World War II, the Occupation, and the Holocaust cast their massive shadows forward in time, obscuring the events of the narrator’s life—one is tempted to simply say, of Modiano’s life—and casting a historical chill over even mundane details like names and places. Like W.G. Sebald, another European writer haunted by memory and by the history that took place just before he was born, Modiano combines a detective’s curiosity with an elegist’s melancholy.