Think of Bertolt Brecht and you do not think of Eros. A fervent Marxist playwright with a handful of masterworks—Drums in the Night, The Threepenny Opera, Mother Courage and Her Children, Life of Galileo, The Good Person of Szechwan—Brecht was also the most revolutionary drama theorist of the twentieth century. His misnamed “epic theater” posited a smashing of theater’s fourth wall and a dispelling of the emotional abracadabra drama casts over its audience. A round-the-clock communist for whom literature was the manifestation of socio-historical pressures, Brecht believed that art should function as the instigation for revolt. Art must be useful, must serve the gritty aims of practicality. No self-important prettiness, no “willing suspension of disbelief,” no Aristotelian catharsis. Brecht would rather you not be so bourgeois as to feel anything; instead, think about what you’re seeing and then go depose your tranquilized leaders.

So viewing a Brecht play can cause the distinct, unsettling sensation of being lectured at by an ideologue, one too often immune to the swivet of love but on quite cozy terms with his own communistic bluster. Although eroticism sometimes pants in his drama—see Brecht’s first play, Baal, and especially his version of Edward II—it comes as a surprise to behold Brecht’s Love Poems, exuberantly translated by the poet David Constantine and the Brecht scholar Tom Kuhn. Spanning the years 1918–1955, this slender volume is only a tease for the dreadnought edition Constantine and Kuhn have planned.

Brecht’s Muses seem never to have shunned him: he penned roughly 2000 poems, in a panoply of registers, in manifold identities and personae, on all aspects of human apprehension. The selection in Love Poems is a memorable and necessary reminder of the feeling artist in Brecht, the craftsman of humanistic, dynamic, erotic emotion—those roiling, fleshly impulses that mark us as animals of higher passion. Their individualist and anarchic vibrancy do much to alter the diffuse perception of Brecht as an apparatchik with creaky polemical aims. What makes Brecht irresistible in Love Poems is how he ponders and prances as if some disaffected offspring of Petrarch and Catullus reared by the Earl of Rochester.

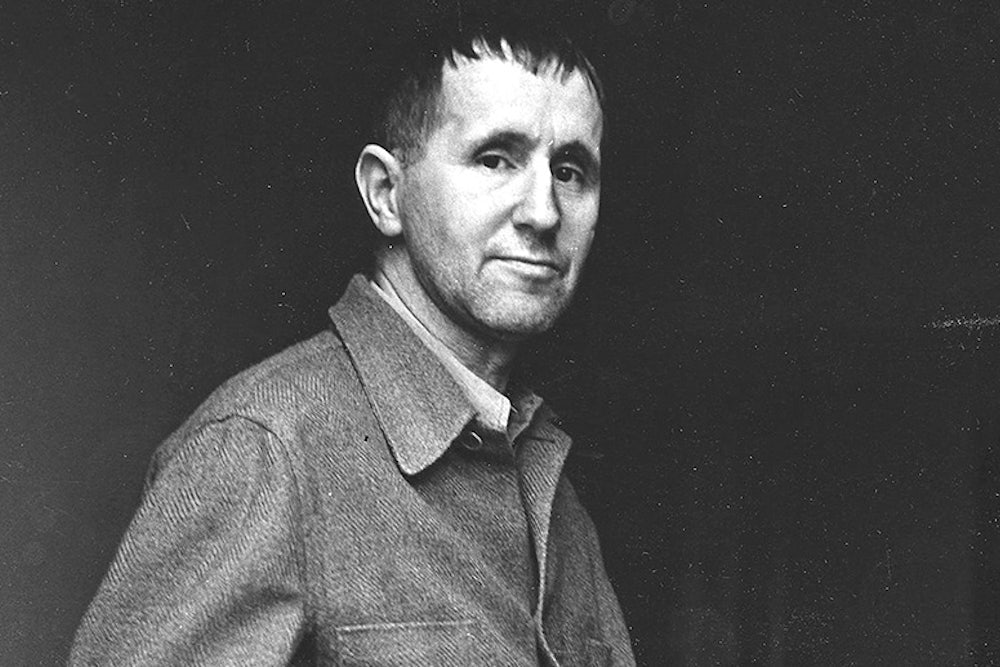

In her endearing forward to this collection, Brecht’s daughter, Barbara Brecht-Schall, writes: “Papa loved women, many women.” Apparently they loved him too, which she finds peculiar because “he did not wash enough and wore long underwear, well after it was fashionable.” (Plus, peek at Brecht’s photo: He’s a slightly less handsome Gertrude Stein.) But the wisdom/talent cocktail, when combined with passion for a cause, can be aphrodisiacal, as many an ugly gent has discovered to his shocked joy. (If ever you’d like to kill the mood, just think of Sartre in bed with de Beauvoir.) An attitude or disposition is one thing, a belief or conviction quite another, and Brecht was nothing if not convicted. As Hannah Arendt wrote of him, Brecht “staked his life and his art as few poets have ever done.”

Brecht’s love poems might just as easily be dubbed the death of love poems, since he is concerned with the vicissitudes of love, with the manner in which one is first defined and then destroyed by love. You get the feeling that sex for Brecht is not just a life-giving bliss in itself, but a private theater in which bourgeois morality is flouted and trounced. If he is never quite unique enough, he is also never unexciting: his plays set out to provoke and prod, and his best love poems match the provocations of his drama, prodding us from somatic complacency and the stultifying mundanity of our domestic lives.

“Like Goethe,” write Constantine and Kuhn, “Brecht was always more or less in love,” and in the poetry that love “is expressed, discussed, enacted in an astonishing variety of modes, forms, tones, and circumstances.” That astonishing variety imbues Love Poems with their charismatic alloy of pathos and empathy, of ebullience and eroticism. The yearning is authentic: “Oh you can’t know what I suffer/ When I see a woman who/ Sways her yellow silk-clad bottom/ Under skies of evening blue.” The naughty admiration is authentic too—“She had some real talent in that bum of hers./ … eager thighs/ Performing tricks with gusto and desire”—and the buoyantly filthy “Sauna and Sex” is almost worthy of de Sade himself. The sexual silliness might be a tad too much for you: “Lie to her, no one’s got a bigger prick/ And when you sit together, son, be canny/ Keep a firm grip on your axe, or else some dick/ Will stick a pillow underneath her fanny.” Maybe don’t whisper that one to your paramour.

But Brecht could be a superb crooner, in exquisite control of his metrics; Constantine and Kuhn speak of his “technical virtuosity,” and that’s precisely what it is: “Soon life will give up all its substance/ And death itself will lose its hurt/ You’ll take the line of least resistance/ And sleep in peace in the hallowed dirt.” His rhythm, his tempo, the exact pressures of his poetics—when they’re right, they’re flawlessly modulated: “One day extinguished what for seven months shone,” or “You know, whoever’s needed is not free./ But come whatever may, I do need you./ I saying I could just as well say we.” The syntactical decisions very often suffuse an image with lovely, unfamiliar potency: “The evening palely and in great pain began/ to darken.” And then there’s the rare instance when Constantine and Kuhn do Brecht no favors: “And climbing trembling to bed they were/ With a smile by the wind they loved dismissed” (the affrontive syntax means to say that the wind they loved dismissed them with a smile, which, let’s be honest, has a hard time meaning something in any syntax.)

We want our poets wise and world-weary, and Brecht always obliges: “When the wound/ No longer hurts/ The scar does.” About lovers: “It’s a mucky game we play,” and “Trouble in the heart, an old disorder”—that it is. As in Brecht’s plays, you don’t mind when intellection intrudes upon eroticism if you admit the umbilical from one to the other: “And she might pass out/ While he sat over a noble and corpulent tome oppressed/ By the decline and fall of the West.” Nor do you mind the ancient equating of sex and death: “With all the winningness/ Of a Valkyrie desperate for corpses/ She invited him to join her in a little tenderness.”

Harold Bloom, who has an uncommon talent for making an insult sound like approval, once wrote that Brecht was “a timeless womanizer and cad, greatly gifted in the mysteries by which women of genius are caught and held”—a view bolstered in John Fuegi’s accomplished biography Brecht and Co.: Sex, Politics, and the Making of Modern Drama. But here in Brecht’s Love Poems you find tremendous feeling for femininity, such sympathetic exertion for the female plight—a poem apiece for a stripper, an actress, a madam, a prostitute, and a widow, each one lit with avuncular affection. (Prostitutes appear in Brecht’s plays the way alcohol appears in Eugene O’Neill’s.)

In true Marxist form, Brecht would have had a hard time caring less about the soul. There’s certainly nothing wrong with that—scientific materialism has almost everything to be said for it—unless of course you want your art in communion with those important, unseen, occult forces that throb just beneath the everyday strain of things. In the poem “Instruction in Love,” Brecht writes, “I like souls to have some flesh/ And flesh with soul is more alluring,” and that’s the very element you wish would appear more frequently across Brecht’s work: the soul’s vitalizing counterpoint to flesh.

There’s a sense in which Brecht was among the least narcissistic of writers because he wouldn’t comprehend art as an advertisement for the artist’s precious personality. And since literature is a calling that inevitably courts egoism, it’s rewarding to spend time with a writer as seemingly self-negating as Brecht. He had no patience for that breed of idealizing which equates the poet with the prophet or priest. A firebrand whose brand of fire was the antithesis of entertainment, Brecht would agree with Orwell’s contention in “The Prevention of Literature” that “there is no such thing as genuinely nonpolitical literature.”

And yet the poet turns his art to agitprop if his aims are purely political. Dante's is most certainly a political poem, but by its ends and never its means (Brecht refers several times to Dante in this volume). Selfhood yearns for a substance apart from politics, and in Love Poems Brecht understands this better than he does anywhere else in his work. Bertolt Brecht “the lover and love-poet,” write Constantine and Kuhn, is an embodiment of “the desperate struggle to keep faith, hope, and love alive” in times of the dirtiest, direst upheaval.