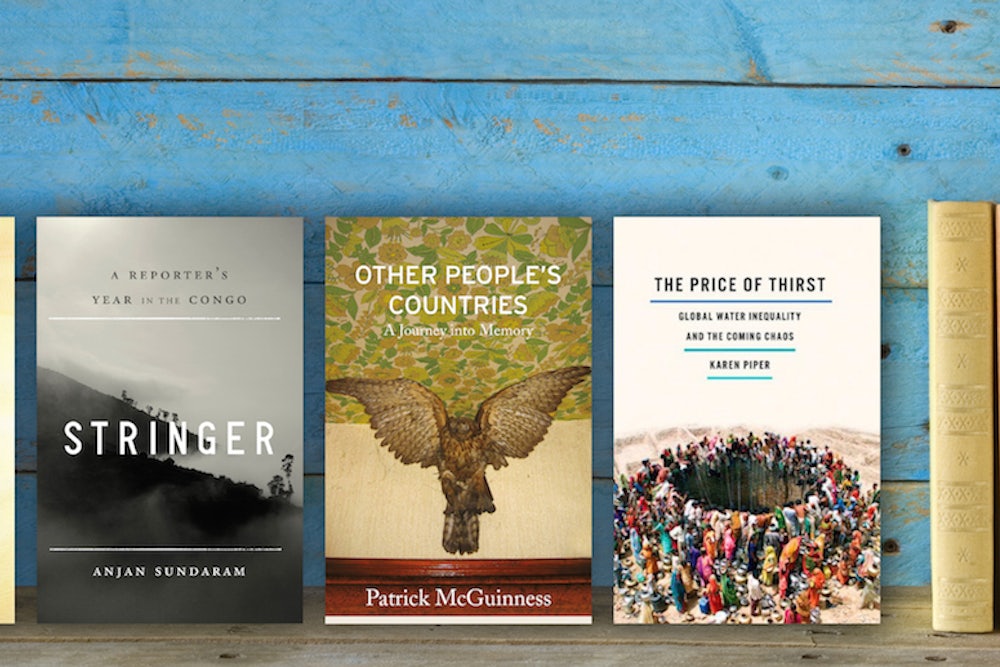

The Price of Thirst: Global Water Inequality and the Coming Chaos, by Karen Piper

“There’s Money in Thirst,” screamed a headline in the New York Times in 2006. In The Price of Thirst, Karen Piper sets off to find the profiteers. She discovers a small number of corporations which, “banking on the fact that the world is entering a global water crisis,” have successfully enlisted the help of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to assume exclusive control of water supplies in some of the world’s poorest corners. Chile is the sole country on earth to have wholly privatised its water. But, travelling through India, Egypt, and Iraq, and frequently exposing herself to grave personal danger (she suffered partial loss of hearing while covering a protest), Piper introduces us to a vast human cast whose access to potable water is progressively diminishing. A backlash by the people being forced to pay for drinking water is not far away.

The Art of Secularism: The Cultural Politics of Modernist Art in Contemporary India, by Karin Zitzewitz

In The Art of Secularism, Karin Zitzewitz brilliantly traces the tragedy of India’s political and cultural degeneration through the evolving work of its most influential painters: MF Husain, Gulamohammed Sheikh, Bhupen Khakar, and KG Subramanyam. The most prominent among them, Husain, was a Muslim whose works celebrated Hindu mythology. In the beginning, he was acclaimed as a national treasure. But with the rise in the 1980s of Hindu nationalism—a project that seeks to transform India, founded as a secular democracy, into a Hindu variant of Islamic Pakistan—he became notorious. Hindus who had never seen his work claimed to be offended by the depiction of Hindu deities in his paintings. Faced with lawsuits and death threats, Husain went into exile. In 2010, at the age of 94, he renounced his Indian citizenship. A year later, he died as a foreigner in a foreign land. The promise of secular nationalism, which once animated the imaginations of India’s greatest artists, now appears extinct. Zitzewitz’s book is an exquisite tribute to some of its most soulful exponents.

Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War, by C. Christine Fair

In this sharply argued work, Christine Fair sheds light on the causes that have turned the Pakistani military into an enemy of its people and a patron of some of the world’s most homicidal militant outfits. As the movement for India’s freedom gained momentum in the 1930s, a tiny segment of the country’s Muslim elite, whose dominance had been disrupted by the British, claimed that their future could only be guaranteed in a country where Muslims were the majority. “Pakistan,” a word invented by a Punjabi oddball in London, soon became a serious political proposition. To its custodians, Pakistan was an embodiment of the legacy of the great medieval conquerors who had unfurled the standard of Islam over India. To inhabit a country created to defend the faithful was to serve the faith itself. Ten weeks into Pakistan’s creation, it waged a war against India to “liberate” Kashmir’s Muslims from non-Muslim rule. It resulted in the first in a series of military defeats for Pakistan. The humiliations on the battlefield complicated the foundational belief that Pakistanis, being descendants of one-time conquerors, were inherently superior to Indian “infidels.” Fair’s book, based on a meticulous analysis of literature published by Pakistan’s military, persuasively demonstrates that the delusions of grandeur which drive the country’s security establishment are rooted in fatal distortions of history.

Other People’s Countries: A Journey into Memory, by Patrick McGuinness

“[T]he paradox of memory,” the renowned poet Patrick McGuinness once wrote, “is that it gives you back what you had on condition that you know it has been lost.” This bargain has yielded rich results for him. The Last Hundred Days (2011), his phenomenal first novel about the collapse of the Ceausescu regime in Romania, was mined from his potted memory of the country. Now, in Other People’s Countries, McGuiness examines memory itself—that deceptive palimpsest created and distorted by time—to recreate the place of his upbringing. For all the charm that its name evokes, Buillion, on the Belgian border, will never attract a more lyrical storyteller than McGuiness. His prose, like his poetry, is a marvel to behold: every sentence is an indelible apercu. This strange and hypnotic memoir confirms McGuinness as one of the finest British authors of his generation—a writer who looks poised, on the evidence of his two magnificent works of prose, to become what Evelyn Waugh called PG Wodehouse: the head of the profession.

Stringer: A Reporter’s Journey in the Congo, by Anjan Sundaram

In 2005, Sundaram abruptly abandoned a promising life in the United States, where he studied mathematics at Yale and had a job offer from an investment bank, and flew to the Congo to work as a stringer. He had little money and no journalistic experience. He lived in one of the poorest neighbourhoods of Kinshasa, found work with the AP, and began filing some of the most insightful stories on the country. Yet, in the hierarchy of journalism, he was on the “bottom rung of the news ladder.” So when elections were held in 2006, his knowledge of the country did not matter to his bosses, who flew in reporters from the West to cover them. Their stories contain no hint of the violence that erupted after the election. It was Sundaram, the neglected stringer, who remained behind as the sole foreign journalist to chronicle the post-election upheaval. This is a searing book—part memoir, part reportage—about a criminally overlooked part of the world.

Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron, by Menachem Klein

Israel, frequently denounced by its critics as a colonial imposition, has a formidable anti-colonial pedigree. However, its subsequent history—condemned to be hyphenated with the Palestinian quest for nationhood—has obscured the pluralistic heritage of the lands over which Israel established itself. In this outstanding work of history, Menachem Klein rescues Israelis and Palestinians from the generals, politicians, and policymakers—and supplies a vivid picture of a time when the great cities of Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Hebron were bastions of diversity in which Jews and Arabs shared a symbiotic relationship. Theodor Herzl’s profoundly humane novel Old New Land, one of the founding texts of Zionism, imagined Israel as a tolerant New Society peopled by visionary Jews and welcoming Arabs. Klein reminds us that such a world once existed outside of fiction.

Homeless on Google Earth, by Mukul Kesavan (published at the end of 2013)

A novelist and essayist, a historian and poet, a social commentator and public intellectual, Kesavan commands an enviable following in the Anglophone world beyond America and Britain. His publisher claims that Kesavan is “the finest living writer of Indian English non-fiction”—and, despite the proliferation of Indian writers in English, it is hard to disagree. In Homeless on Google Earth, a collection of his most trenchant essays, Kesavan mounts an elegant argument for a cosmopolitan sense of belonging that transcends the narrow trappings of identity. Drawing on the disparate origins of his own parents, Kesavan surmises: “If there is a moral to my story, it must be that the reality of ‘home’ is subject to alteration, that the native place is as often a place of transition as it is a point of origin, that instead of being a still centre to which we are historically attached, home is an idea to which we choose to belong.” And, writing in the land of the Holy Cow in which Hindu chauvinism is now backed by political muscle, he is funny and provocative at the same time: “The cow is a creature of the most supreme stupidity. No wonder the Hindus warm towards it. Donkeys have some semblance of an impulse to spontaneity. Cows are distinguishable from plants because they move.”