There are two million home health-care workers in the United States, and not one of them is guaranteed minimum wage or overtime pay under federal law. That's because in 1974, amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act exempted all workers who provide “companionship services.” Over the past few years, the Obama administration has been trying to rectify that mistake and ensure “that men and women in one of the fastest-growing professions in the country don’t slip through the cracks.” But a federal judge, who is expected to issue a ruling on Wednesday, stands in the way1.

In September 2013, the Department of Labor (DOL) announced a new rule that would essentially narrow the definition of “companionship services” to people providing more social interactions with elderly clients, such as playing games, doing crafts, reading and going on walks. Home care workers providing more substantive care, and those employed by third-party agencies, would be eligible for minimum wage beginning January 2015.

But three home care lobbying organizations—Home Care Association of America, International Franchise Association, and the National Association for Home Care and Hospice—sued the DOL in June 2014. U.S. District Court Judge Richard Leon heard the first part of Home Care Association of America v. Weil in December 22, 2014, eventually striking down the section that would require third-party employers to provide minimum wage and overtime protection to home care workers. He called the regulation “an arbitrary and capricious exercise of authority inconsistent with Congress’s language and intent,” and placed a stay on the entire act until January 15. He is expected to rule Wednesday afternoon on the administration’s new definition for companionship services.

Deane Beebe, spokeswoman for the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, said a ruling against that new redefinition would be a blow to millions of workers—more than 90 percent of whom are women, while one in five is a single parent.

“The DOL tried to correct this antiquated rule,” she said. “These women have been waiting for over 40 years to get the same federal labor protections as other workers in this nation.”

Leon wrote in his December opinion that the rule would “have a destabilizing impact on the entire home care industry and will adversely affect access to home care services for millions of the elderly and infirm.” The National Association for Home Care & Hospice said after Leon's decision that the changes "would have led to higher costs which would have been borne by infirm individuals or by the states and federal government through financially strapped programs such as Medicaid."

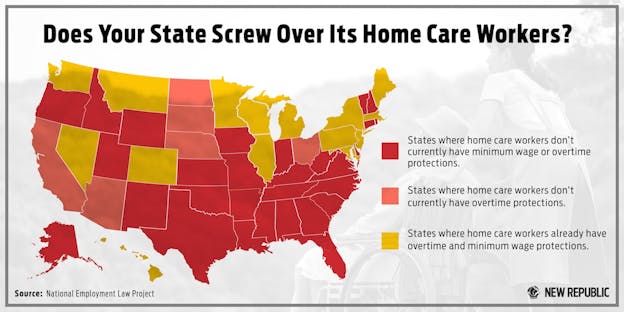

The Obama administration had already bowed to pressure from states last October that said they would need more time to put such changes into effect, and announced that the rule wouldn't be enforced until after June 30, 2015, and that the DOL would “exercise its discretion” on enforcement the following six months. Currently, 15 states already provide minimum wage and overtime protection to home care workers, and six states plus the District of Columbia provide at least minimum wage.

As we noted last year, being a personal care aide—a type of home care worker—is one of the ten worst-paying jobs in America. But as the Baby Boomer generation ages, home care workers will become increasingly essential. Between 2010 and 2050, the elderly population is expected to double to 88.5 million, according to a 2010 report by the U.S. Census Bureau. The elderly-disabled population will, of course, grow too: According to the National Down Syndrome Society, life expectancy for an individual with Down Syndrome in the 1980s was 25 years, and today it’s 60. Despite the difficult work and low pay, home care employment is expected to grow by 48 percent by 2022, in part due to the growing elderly population.

The direct care profession, which includes home care workers, is plagued with high turnover rates. According to a 2011 report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, approximately 30 percent of home health aides would want to leave their jobs to find a better job, and 30 percent would leave because of poor pay. According to the same survey, about 46 percent of home aides have had more than one job in the past two years.

A guaranteed minimum wage has been shown to increase job retention and quality of care, and a study released in 2005 on home care workers in San Francisco found that increased wages increased retention rates by 17 percent.

“We need to invest in these workers to ensure we have quality care for the people who need it,” Beebe said. “If the wages are low and you don’t have basic labor protections, whose going to take these jobs?”

On Wednesday, U.S. District Court Judge Richard Leon vacated the DOL's redefiniton of "companionship services," stating that "Congress is the appropriate forum in which to debate and weigh the competing financial interests in this very complex issue affecting so many families."