This piece originally appeared in The New Republic on Feb. 5, 1916.

One of the unsung advantages of democracy is that of being consistently and unblushingly illogical. No despot, for instance, with any regard for his reputation could possibly have treated the education of the American Negro in such perfectly contradictory ways as has been done in this republic.

Avoiding controversy by confining himself to the period preceding the Civil War, Dr. Woodson has set down calmly and methodically the facts concerning our attitude toward Negro education for some two hundred and forty years. It is one of those tales which introduce us to a world tragedy.

Imagine, for instance, the forefathers facing this problem of human training: Here are Negroes. They are slaves. They ought to be slaves. Consequently they must be trained as slaves. Then enters the devil of illogic: they have immortal souls, consequently they must be trained as Christians. No sooner, however, is an attempt made to train them as Christians than, lo! they get some dangerous intelligence. Anxious search ensues for methods of training slaves in Christianity without making them intelligent. “Religion Without Letters,” Mr. Woodson calls it.

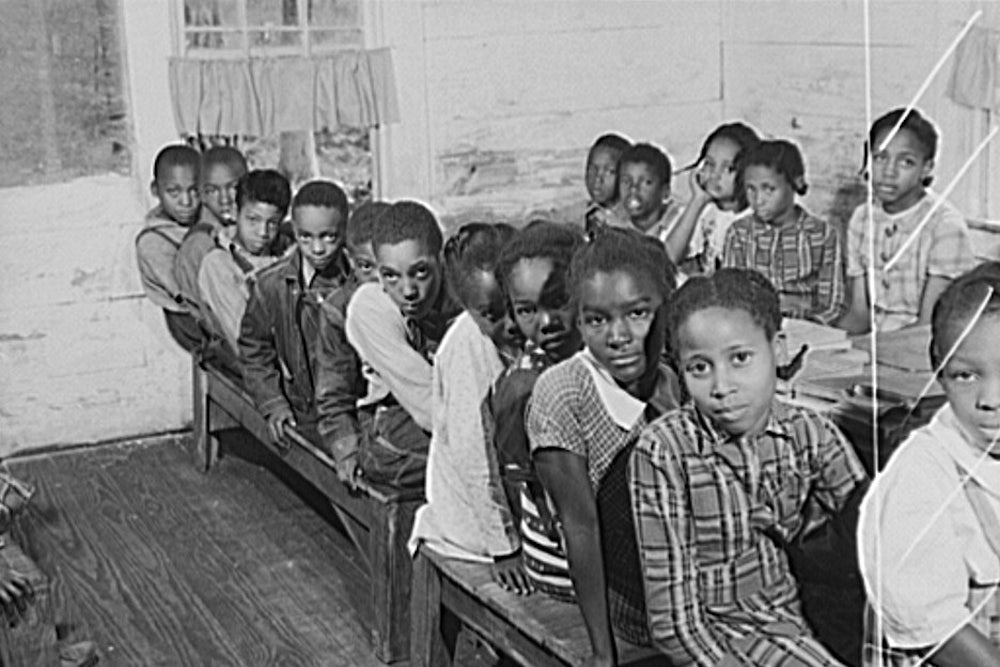

Meantime, before the magic method is discovered, the sparks of undesired intelligence spread. Free Negroes, even slaves, begin to educate themselves. Schools start up here and there, and matters look really alarming. Some black leaders appear, in religion and even in revolt. About 1835 comes determined reaction. We have gone quite far enough, whisper the advocates of slavery, and their whispering is reinforced and strengthened by a new economic note, for the cotton kingdom is rising. The kingdoms of silk and wool are receding, the American slave is to become an economic foundation stone, a new industrial element. Down with education—up with slavery! Religion must still be taught, to be sure, for properly taught it makes better slaves; but no reading and writing, no real training of intelligence.

There ensued a long and dismal fight in which education became a thing of midnight strategy, a stolen wonder. Even the free Negroes of the North suffered from the reactionary blows. They were swept out of the public schools even in the few places where once they had entered. They established their own weak little institutions with difficulty and amid threats. Still the work went on doggedly and persistently, and bolder whites helped. Who does not remember Beriah Green in New York, and Prudence Crandall and her Connecticut troubles?

Slowly separate institutions and separate colored school systems arose. Gradually down toward wartime some little education here and there was provided at public expense. Indeed, the whole tale shows that by being frankly illogical a democracy may do exactly the thing which it has started out not to do and never know the difference.

Practically everything that happened before the war has been reproduced in larger scale since the war. We trust Dr. Woodson will not forget to tell us this later story, even though it raises much discussion and bitter controversy. Here we have again Negroes. They are serfs. They ought to be kept “in their place.” They must therefore be trained as serfs. The illogical devil appears: Negroes also have brains. Modern work needs brains. But if we educate Negroes to work they may get sense enough to want to vote and even to know how to vote. Therefore, “industrial” training without the training of intelligence—but this is a tale for another book. Meanwhile the author has written a book worthwhile. It is provided with ample references, an appendix of original documents, and a very complete bibliography.