Mom pressed my index and middle fingers together, then did the same with my ring and pinky fingers. She spaced the two pairs apart, and there it was: that Vulcan salutation, something she had taught my older brother to do before I was born, and now he could do it with both hands. I must have been no older than five or six, sitting on the countertop and swinging my legs. Before I knew the word Trekkie, I knew "Star Trek" was a special kind of TV show, different than the others we watched together as a family. This was mom’s favorite, and more than that, it was a part of her life in a way "The X-Files" and "Seinfeld" were not.

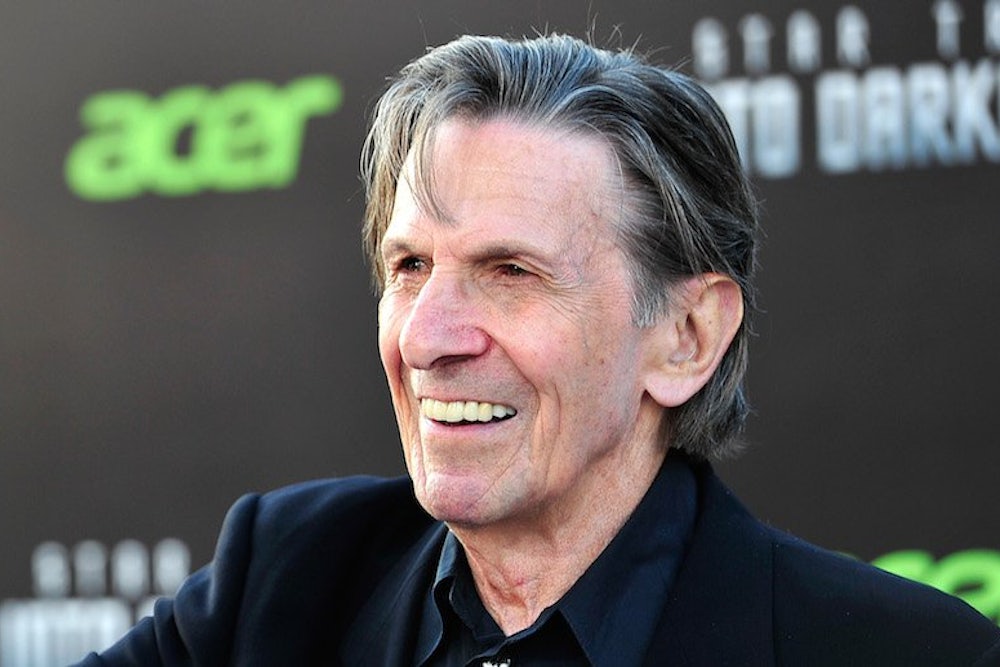

So I was not surprised at her distress last Friday when Leonard Nimoy passed away. Nimoy was most famous for his role as the iconic extraterrestrial Spock, though he was also a poet and prolific voice actor. In light of his long career it feels somewhat shallow to pay homage to his life only through the lens of "Star Trek." But it was through that legendary franchise that Nimoy impacted my life, in a small and local way that still seems almost immeasurable. Others, I'm sure, feel the same.

Consider 1970s North Texan suburbia: This was my mom’s teenage milieu. Rows and rows of identical ranch houses, manicured lawns; a life of backyard barbecues, God, and football. Mom was tall and thin, pretty and athletic, but deeply shy. These days there would be plenty of ways for a girl like her to explore all kinds of interests—but back then, when mom tried to sign up for drafting classes as a high school elective, her guidance counselor insisted she take home economics instead, being a girl. And so she did. In private, though, she nursed a secret hobby.

"Star Trek." All things "Star Trek." Mom watched the original series reruns that had aired between 1966 and 1969; she signed up for mailing lists that sent out hard-copy fan fiction. She saved up her babysitting money and bought model kits from Kmart, from which she produced handmade miniatures of the Starship Enterprise and its bridge. She hung the spaceship up with yarn from her bedroom’s air vent, so that when the air blew the vessel would pitch and spin as though careening through space. But when friends visited, she would hide the models in her closet and keep her fandom to herself.

After all: In the ’70s nerds didn’t have the cultural cachet they do now, and they especially didn’t there in culturally conservative North Texas. There was no Sheldon Cooper to cast geekdom as cool and make the case that the dweebish and cerebral have a place in the order of things.

Mom had to keep her nerdiness a secret. She would have felt totally alone, were it not for the community of similar secret-keeperswho came together to develop the "Star Trek" fan community. The density and intensity of "Star Trek" fandom is a cultural phenomenon, the high-water mark of devotion by which we can measure other fandoms. It has been studied by scholars as a religious phenomenon, and given its many sacred symbols and shibboleths it isn’t hard to find the framework plausible. And though mom probably would have benefitted from personally interacting with like-minded fans, she never made it to a conference: very few were near enough to her home in Texas to make the trip possible.

She did go to hear Leonard Nimoy speak though, just one time. It was shortly after the 1975 publication of Nimoy’s book I Am Not Spock; he was giving a talk at the University of Texas at Arlington campus. My mom couldn’t drive yet, so she begged my grandmother to drive her, despite her parents' squirmy discomfort with her odd preocuppations. Mom was rapt; she can tell you all about it to this day—the things Nimoy said, the poetry he read aloud, the "Star Trek"-related questions he tolerated.

Mom had gone as a Trekkie to see Leonard Nimoy speak, knowing that the content of the lecture was specifically focused on his work outside the franchise. As I was writing this essay, I called her to ask why.

“Because,” she said, “what he was saying was, people are more than the characters they play.”

And to her, that’s what "Star Trek" was all about anyway.

The political landscape of Texas in the 1970s was heated, tense, resistant to change. Texas school districts fought desegregation for over a decade spanning from the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision well into the late sixties. In 1970, the resolution of the court case United States v. Texas resulted in the Texas Education Agency being given the responsibility and authority to end segregation and racial discrimination in Texas public schools. After the state’s long fight against integration, the desegregation order sent a cascade of shockwaves crashing through Texan schools. State politicians and disaffected white community leaders complained vociferously about the decline of segregation.

Texans’ general antipathy to federal power—coupled with recalcitrant southern racism—meant that positive narratives of desegregation were relatively scarce in mom’s community. And she might have bought into the dominant indignation of her neighbors, had it not been for "Star Trek," which seemed to beam into her quiet suburb directly from the future.

And the future that "Star Trek" presented was a decidedly utopian one. Its vision included no money, no consumerism, and a great deal less prejudice. Nichelle Nichols, the black actress who played Lt. Uhura, reported in her autobiography that Martin Luther King Jr. convinced her to stay on "Star Trek" because her role presented a groundbreaking opportunity to display a fully fleshed out black character in a mainstream venue. "Star Trek," King reportedly told Nichols, was the only television show he and his wife allowed their children to stay up late to watch.

Rightfully so: aside from including Nichols and a variety of other non-white cast members (such as George Takei as Lt. Sulu) in pivotal roles, "Star Trek" took a deep, considerate view of personhood. Though an extraterrestrial, Nimoy’s Spock was—in the famous words of William Shatner’s Captain Kirk—“the most human” of all the souls that captain had ever known. Spock’s humanity was premised not upon his DNA, his culture, or his appearance; in all these areas he was distinctly alien. It was his curiosity, his loyalty, his selflessness, his humane and thoughtful disposition that made him human—a way of looking at personhood and worth that subverted the prejudice still dominant in the era when "Star Trek" debuted.

That a person’s character should be the primary source of their merit, rather than their culture or physical constitution, now seems a closed matter. Whether or not that is really the case, it certainly wasn’t when my mom was a teenager; when she was learning to believe, contrary to all input from her non-Trekkie neighbors, that the roles we play in life are not the full measure of who we are. It was apparently a lonely conviction, but the far-flung community of Trekkies she kept contact with through mailing lists and chance meetings in public shored up her courage. She passed all that on to my brother and me.

There was more. "Star Trek" opened mom’s imagination up to science fiction, which she consumed voraciously, and she shared that love with my brother and me. I can remember her reading A Wrinkle in Time to us in the evenings until she went hoarse; we spent many afternoons at museums around town soaking in the exhibits. When book fairs came around during the school year, she was easy to persuade into purchasing. And my brother and I read, and read, and read.

Being a bookworm wasn’t much more popular by the time I made it to high school than it had been when mom was a student, but I had the benefit of her encouragement. Mom got me to debate tournaments and essay competitions, academic decathlons and speech contests. I was dorky, but mom’s support was earnest: cynicism and revanchist geekdom are easy to come by these days, but mom really believes in exploration. It’s the Trekkie in her.

I will confess: I never liked watching the original "Star Trek" all that much—especially before the shimmery, lens-flared 2009 reboot, which was met with mixed feelings by purists—because the special effects are corny and the acting tends towards the soap-operatic. As a young kid I categorically resisted the show, but as I’ve grown older I’ve grown more amenable to joining mom on the couch.

A few Christmases ago my brother and I bought her a set of lapel pins in the shape of "Star Trek" crew insignias, and sometimes when mom wears her Captain’s pin or Science Officer pin, she receives a few salutes, or a Vulcan salutation from plainclothes Trekkies in the streets of our town. For a brief period in my adolescence, I was a little embarrassed by the public display, but now I’d like to express my gratitude for it. The show gave a generation of hopeful introverts like my mom a community, and a way of looking at the world with a focus on discovery and solidarity rather than prejudice and power. Nimoy's Spock, with his quiet dignity and earnest intellectualism, was a crucial part of the ensemble that gave "Star Trek" its texture and depth, and Nimoy himself lived its ethos superbly.