President Obama met with the Congressional Black Caucus in a contentious closed-door session two weeks ago to discuss historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). He reportedly said that those schools that could not improve their business practices and graduation rates should, as Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA) characterized the remark, “go by the wayside.” Many members left the meeting trying to reconcile how the first black U.S. president could employ such cold calculus on HBCUs.

The president is correct, however. When any college, let alone an HBCU, perpetually fails black students, the federal government needs to side with those students, not sanctify the institution. Salvaging a student body that’s been underserved by a poorly performing university is a higher priority than granting numerous reprieves in hopes that the school’s deficiencies will eventually be corrected. In an already tight budgetary environment, the president should ensure federal funds supporting HBCUs and students are funneled to the best black schools that produce the best outcomes.

President Obama’s criticism is not a commentary on the necessity and value of HBCUs, but founded in the empirical facts of black student statistics. The four-year graduation rate for students at all HBCUs is only about 20 percent; the rate for predominantly white colleges and universities is more than twice as high. All public schools graduate less than 12 percent of their black male students in four years. For-profit institutions graduate only 10 percent of their black female students in the same timeframe. Generally speaking, higher education is failing black students.

This matters because HBCUs don’t simply exist to educate; their unwritten function has always included a social mandate to better the station of African Americans. For the ones that have routinely failed to handle this responsibility, there is little rationale for sending them vulnerable students and already scarce federal dollars. It is not that their students are less capable, even if they may arrive at HBCUs less prepared. Rather, it is a confluence of institutional factors that cause the school’s failure.

HBCUs face significant, well-chronicled challenges. They are routinely shortchanged in state funding; financial mismanagement continues to plague some of them; alumni giving is notoriously low, reducing the school’s ability to meet shortfalls with cash on hand; and the Obama administration’s changes to Parent PLUS Loan program requirements cut deeper into their balance sheets. The changing nature of higher education—such as online offerings and for-profit universities that cater to non-traditional and low-income students—has carved into the population from which HBCUs typically have drawn their student bodies. The result: HBCUs are disadvantaged in the competition for the highest achieving students. Further, HBCUs have lower six-year graduation rates than the average of all first-time black students at colleges and universities nationwide.

South Carolina State University knows these issues all too well. Last week, citing a $17 million deficit, a 14 percent four-year graduation rate, and low enrollment, state representatives considered closing the university for two years. That is a move that, had it happened, almost certainly would have led to the university’s demise. Instead, lawmakers decided to fire SCSU's leadership and place the state’s Budget and Control Board temporarily in charge. Though this is an atypical state of affairs for most HBCUs, it is the exact sort of examination supported by the president.

These struggles do not negate the importance of preserving HBCUs. Administration officials are quick to point out their appreciation of these institutions, through a long-running White House initiative and a recent $25 million cybersecurity grant. But when HBCUs fall short, there will be no federal bailout waiting. President Obama made clear that these troubled HBCUs are not too black to fail. The black student, not the black university, should always be the focus of our national effort, and the recipient of our allegiance.

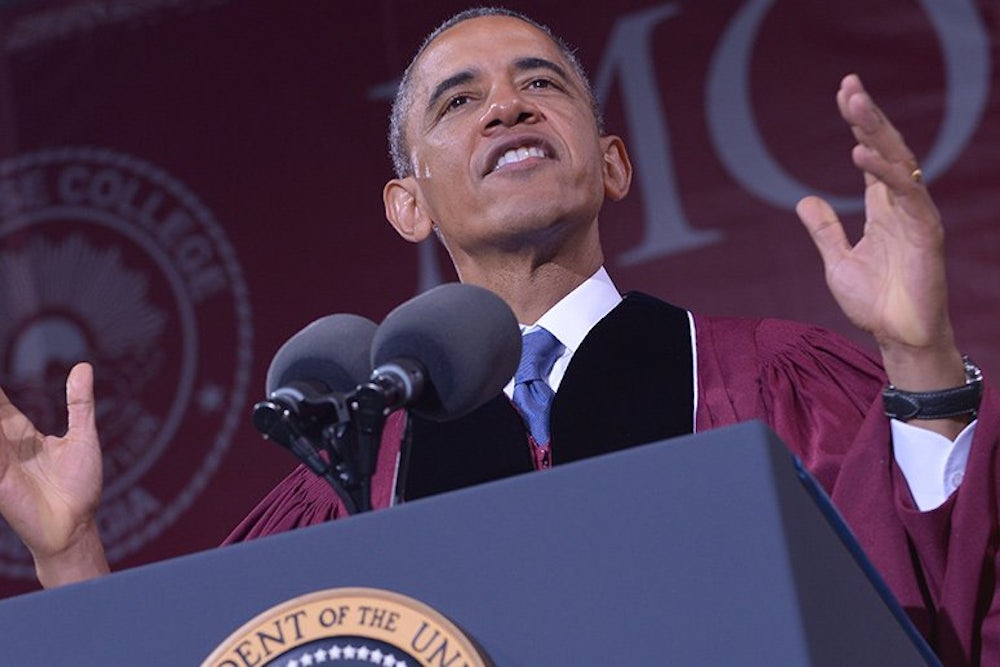

In his 2013 commencement address to Morehouse College, the president told the graduates, “Nobody is going to give you anything that you have not earned.” he might as well have been addressing the administration and faculty sitting behind him.