A six-month Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation validated what we heard from many Ferguson residents after the August shooting death of Michael Brown drew the nation’s attention to their city: that their police department has, for several years, exhibited a disturbing pattern of discriminatory policing—and, frankly, grift of its citizens.

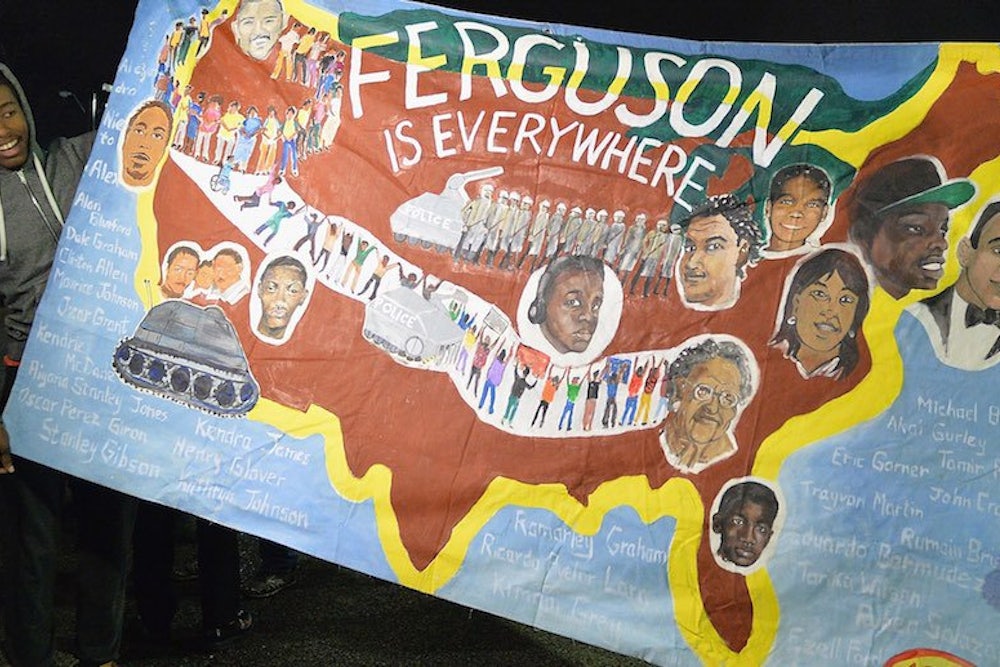

Further action by the DOJ may reform (or even overhaul) the Ferguson police department entirely. The shooting of two police officers from neighboring departments early Thursday morning in front of the Ferguson police headquarters will likely add pressure for resolution sooner than later. But, while attention to the ongoing tension in Ferguson is merited, there is a danger in Ferguson remaining virtually alone in the national spotlight. The problem of police brutality is hardly endemic to that one city. What about the rest of the 18,000 other departments across the country that may have similarly sick cultures and procedures?

Other Fergusons loom on the horizon, and we shouldn't wait until an officer shoots another person and a city erupts to fix them. The lessons emerging from Ferguson can and should guide a nationwide overhaul to police reform. Now, while the whole country is focused on this issue, we should seize this moment to develop solutions that are as comprehensive as the problems are vast. Police misconduct and brutality are ingrained in departments thanks to bad practices, limited transparency and a lack of accountability. How does a federal government charged with protecting citizens from policing like this provide a fix that sticks?

It isn’t as if they haven’t tried in the past. In the wake of the LAPD’s beating of Rodney King in March of 1991, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act was passed in 1994. One of the things it mandated was that the DOJ keep records and report on use of force by law enforcement. The law also empowered the DOJ to sue any police agencies they found to exhibit a “pattern and practice” of excessive force and civil rights violations, and enter with them into “consent decrees,” arrangements that give the DOJ oversight over a police agency for a designated period of time. The goal of these arrangements is to reform a police department’s policies and practices by monitoring performance and making recommendations.

In the two decades since the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act was passed, the DOJ has entered into more than 20 consent decrees with local police departments. They have a record of effectiveness, the most notable example being in Los Angeles where the King incident occurred. A study by the Harvard Kennedy School, found that the DOJ's consent decree with the LAPD improved the department in most ways imaginable. Public satisfaction with the police improved, the frequency of the use of serious force fell, the quality of police stops improved with stops resulting in a higher rate of arrests and charges filed—all while crime rates fell.

The successful use of consent decrees by the DOJ supports the idea that comprehensive federal oversight of the nation’s police can improve outcomes. But what we’ve ended up instead with is a piecemeal, reactionary system for police accountability that can barely keep up with, let alone disrupt, the warrior cop culture that has poisoned so many departments with its misconduct and brutality.

The mandate that the DOJ record and report on use of force, for example, is hollow without the cooperation of the country’s 18,000 police departments. It isn’t enforced today, and thus we have no comprehensive count of how many people are killed each year by the police—the most fundamental information needed for reform. In addition, the DOJ currently investigates police misconduct primarily by complaint. And its consent decrees, while shown effective when enforced, are temporary and only apply to individual police departments with track records of misconduct. They are not the permanent, preventative, and national measures that are needed.

A consent decree is likely on its way in Ferguson, and it promises to be an effective step towards reform. But what happens after the DOJ removes its watchful eye from that town, perhaps to address other Fergusons that face similar treatment by their police departments?

The prevalence of police brutality has long demanded federal intervention. The White House task force prescribed in its first report last week good, common-sense measures for better policing, including independent investigations in fatal police shootings and more comprehensive data collection. But that doesn’t get close to a permanent solution.

The Civil Rights Division of the DOJ has demonstrated its effectiveness in addressing police misconduct through the enforcement of the aforementioned 1994 Violent Crime Control Act, as well as the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Special Litigation Section currently does that work, but that unit is also responsible for protecting disability rights, the rights of the incarcerated, reproductive and religious rights.

The DOJ's Civil Rights Division would be strengthened by the creation of a section charged solely with tracking, investigating and—where a civil rights violation is found—prosecuting use of force. Such a unit would prioritize those duties and present a national solution to what is undoubtedly a nationwide problem. The department is already empowered by existing law to create such a unit that could take broader action. Perhaps the only thing standing in the way is the political will to impose a penalty if local police departments do not cooperate.

More than 20 years passed between the assault on King and Brown's death. In that time, untold numbers of unarmed Americans have been killed by police. Their deaths did not become national news stories or spur federal investigations. We owe it to them to make fair and safe policing a matter of national interest and urgency. If we don’t, the list will grow and we’ll be here again.