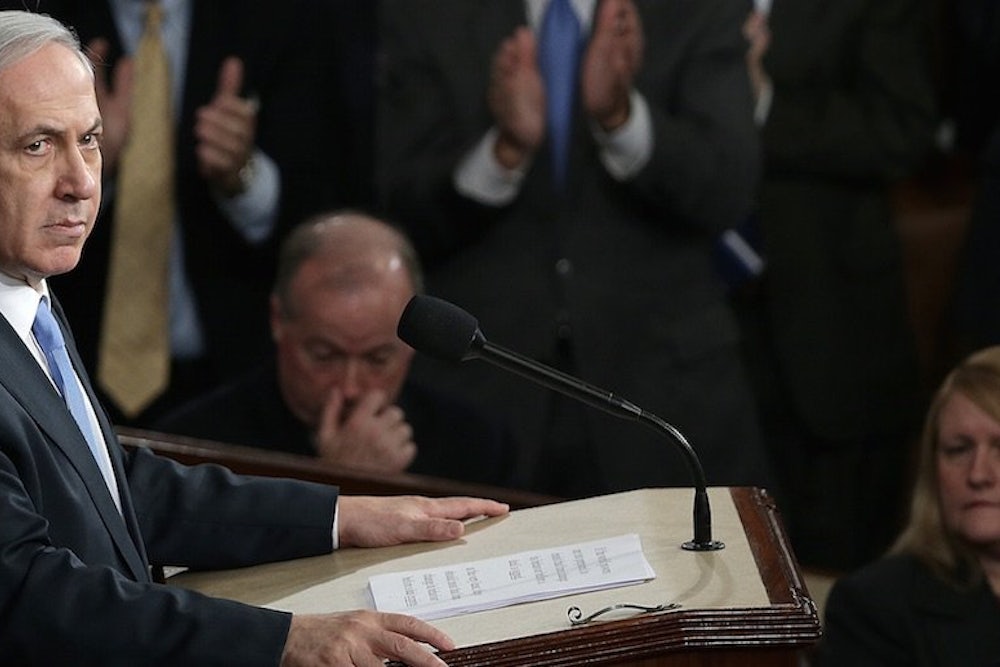

On March 3, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivered his controversial speech to a joint session of Congress, where he undermined President Barack Obama by calling for a tougher deal to restrict Iran’s nuclear program. Before the speech, Netanyahu had been slipping in the polls, but he still faced no domestic challenge to his foreign policy. Bibi thought, not unreasonably, that this would play to his strength and demonstrate to Israeli voters that even though his relationship with Obama is sour, America was as solidly behind him as ever.

But the plan backfired. Despite the many standing ovations and warm reception Bibi got in Congress, Democrats were outraged. Several dozen did not attend the speech, including Vice President Joe Biden. Others attended, but issued statements expressing their objections.

Perhaps even more importantly, the speech caused enormous uproar in the overwhelmingly Democratic American Jewish community. While the influential American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) did not issue a statement about the speech, they must have been displeased by Bibi’s disregard for the bipartisanship that is AIPAC’s lifeblood. Moreover, the speech pushed Senate Democrats closer to Obama’s position on Iran’s nuclear program, making a veto override of a new sanctions bill look all but impossible.

What Bibi thought would give him a nice boost in the polls took him backwards and took an issue he had a monopoly on and made it legitimate fodder for his opponents. Bibi had interfered in American politics and had angered not only the Obama administration but also a lot of congressional Democrats, as well as many in the American Jewish community. While polls immediately after the speech showed a small bump for Netanyahu, his numbers started declining as the controversy continued to simmer.

On March 17, Israelis will be going to the polls to elect their new government. Israelis will be voting much more on domestic concerns, but the fallout from the speech has put foreign affairs much more prominently on the agenda than they had been before. While that is still a base of strength for Netanyahu, it is much less so now that he has apparently strengthened Obama’s hand in pushing for a negotiated settlement that Iran can accept.

When the Knesset was dissolved on December 8, 2014, and new elections were first called, few believed Netanyahu would face a serious challenge from the center-left. Netanyahu’s campaign was crafted to stave off his challengers from the right, chiefly Naftali Bennett’s Jewish Home party.

But a funny thing happened on the way to Jerusalem. Netanyahu succeeded in distancing himself from Bennett in virtually every poll, and yet found himself trailing someone else entirely: As the last surveys of Israeli voters came out, the Zionist Union (ZU) coalition, led by Labor Party head Isaac Herzog, was leading Netanyahu by anywhere from three to five seats in the next Knesset.

A few months ago, Netanyahu’s continued reign seemed assured. Now he's in an increasingly desperate fight to save his political career. Bibi attributes it to "a great, worldwide effort" to topple his Likud Party, but really he has no one to blame but himself.

Several controversies within the governing coalition led to the decision to disband the last Knesset. These included a bill that would enact a law declaring Israel to be “the nation-state of the Jewish people,” which more liberal parties opposed; controversies over the budget, which sharpened some serious disagreements between Netanyahu and Finance Minister Yair Lapid, of the centrist Yesh Atid party; and a law to ban free newspapers, aimed at American-Jewish casino mogul Sheldon Adelson’s Israel Hayom newspaper, which is widely seen as a pro-Netanyahu platform but has risen to the top circulation in Israel simply because it is free.

These debates were held not just between the governing coalition and the opposition, but between the right wing and centrist parties in the government. Bibi had visions of a new coalition, even more rightward-leaning, which would be less contentious, especially on foreign policy issues.

With his focus on his right flank, Netanyahu was dismissive of the Labor Party and its leader, Isaac Herzog, believing that Israelis would not be willing to trust their security to a man without significant diplomatic or military experience. That dismissiveness extended to issues that were at the core of the election for many Israelis: the economy and social welfare. Prices have gone up in Israel while wages in most sectors have stagnated or declined. The housing market, in particular, has been a focus of this problem. Netanyahu’s budgetary priorities have been questioned by many, particularly as cuts to social welfare sectors like education and health care have occurred alongside increased funding for settlements in the West Bank.

Herzog, recognizing that his lack of international experience could doom his campaign, struck a deal with Tzipi Livni, the one-time foreign minister and long-time point woman for negotiations with the Palestinians, and together they formed the Zionist Union coalition. Livni’s Hatnuah party was facing the distinct possibility of falling short of the requisite votes to qualify for a place in the Knesset, and her presence improved Herzog’s credibility.

What really boosted the Zionist Union was Netanyahu himself. Despite his three terms in office, Netanyahu is not a particularly popular leader. Much of his support comes from being perceived as the best of a bad bunch of options across the political spectrum. In terms of personal appeal, Bibi is perceived as a stronger leader but repeated scandals over personal use of state funds and his constant doomsaying have largely eroded his advantage over the decidedly bland Herzog.

When social or economic issues came up in this campaign, Bibi routinely started talking about Iran, the Islamic State and Hamas. While it’s certainly fair for an Israeli prime minister to campaign on security, it became clear that Netanyahu was simply refusing to engage on the issues that were polling as the top priorities for Israeli voters. Matters got worse when a damning report put the blame for high housing prices squarely on Netanyahu’s shoulders. Still, Netanyahu steadfastly shifted the subject to Iran or Hamas, only attempting to address economic issues in the waning days of the campaign. It may be too little, too late.

The Zionist Union stands a good chance of winning the most seats, but that doesn't necessarily mean they’ll lead the next Israeli government. They would need to form a coalition of at least 61 seats, preferably more (Israeli governments are very fragile things, and a small majority puts the entire coalition at the mercy of every small party it includes). That seems possible, but far from certain based on current polls, particularly because they are likely to shun a significant potential partner. It seems very likely that the Joint List, made up of Israel’s two largest Arab parties and the Jewish-Arab communist party, Hadash, will garner a significant number of seats, but no Israeli governing coalition has ever included Arab parties. Herzog and Livni seem unlikely candidates to buck that strong precedent. Even if they do so, it is far from certain that the Joint List would be willing to join any Israeli government. They have stated they would not, although a recent poll of Israel's Arab population shows majority support for them doing so.

Of course, a lot can change in the days between the last major Israeli polls and the election. Israeli polls are notoriously fickle things. In 2013, the polls failed to predict the stunning success of the Yesh Atid party, for example. It is certainly possible that Likud could outpoll ZU. If it does, Netanyahu will have his own problems forming a coalition, but the field looks less complicated for him than it does for Herzog.

But what if the Zionist Union manages to form a ruling coalition? Herzog, with Livni’s full support, has made it clear that he would prioritize mending relations with the United States. And one part of that process is certainly going to be working to revive a peace process with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. While the rancor of recent years, on top of the frustration of 20 years of fruitless talks while settlements expanded, have made that more difficult, Abbas is probably the last Palestinian leader who will be willing, not to say eager, to give negotiations one more shot.

Herzog has already made it clear that he has little sympathy for the settlements outside of the major blocs, which most peace plans envision staying in Israeli hands, with Israel compensating the Palestinians for that land. So it’s likely that a Herzog victory would be enough to get a process started again, and ease international pressure on Israel. Whether he can close a deal is another question. The right, which will be led by Likud, will be hampering him at every turn, and the Israeli public remains skeptical of Palestinian intentions.

But Herzog is unlikely to take any bold steps for peace until he is buoyed by significant success or driven to desperation by failure in the domestic sphere, which is why his main focus would be on domestic issues, notably the economy. Still, a victory would mean an end to Netanyahu’s intransigence. Given the dismal prospects for a negotiated solution today, that represents real progress.