FERGUSON, Mo.—The polling place where Michael Brown would have been able to vote is a three-minute drive from the spot where he was killed nearly eight months ago. It’s a walkable distance, and easy to navigate. It’s harder to locate the actual voting area inside the Koch School, a small elementary campus that forms its own cul-de-sac at the end of Exuma Drive in Ferguson's Ward 3. The arrows on the wall help, but they’re lost amid the colorful motivational posters and images of the school’s Cougars mascot. Once you find the room, the voting booths are lined up in front of a large blue curtain that walls them off from the small gymnasium. When I arrive there, at 4 p.m., no one is in line for a booth. No one is at a booth. Polls close at 7.

Later, a poll worker tells me the pace of voter traffic has been about what it usually is in this area. Knowing that only 12 percent of registered voters in Ferguson Township cast ballots in last year’s election, I'm not heartened.

I head outside, where the morning’s rain had long since stopped. Missouri State Senator Maria Chappelle Nadal is greeting voters driving and walking to the school, while campaign volunteers encourage those folks to cast their city council vote for Wesley Bell, a community college professor, prosecutor, and part-time municipal judge.

With this election on Tuesday, Ferguson faced a crossroads. One month after a Department of Justice report condemned systematic abuse in the city’s police department and courts, residents had the chance, many believed, to change how their local government operated. That opportunity was created largely by the report's fallout: John Shaw, the city manager who oversaw the government and police force, resigned, along with the Ferguson court clerk who had sent racist emails from her city address. To boot, three City Council members declined to run for re-election.

The shakeup opened the door for candidates. There was an established local politician and an upstart young lawyer. An activist who had marched in protests ran, and long-time residents sought office for the first time, animated by Brown’s killing at the hands of former police officer Darren Wilson. For the past several days, people have reminded me that contenders for City Council typically ran unopposed. That wasn’t the case in 2015, when eight hopefuls vied for three spots—half of the council that soon will choose a new city manager. In turn, that person will choose the new police chief and court clerk. If Ferguson is to see real change in its corrupt government, it needed to begin with this ballot. It needed to start Tuesday.

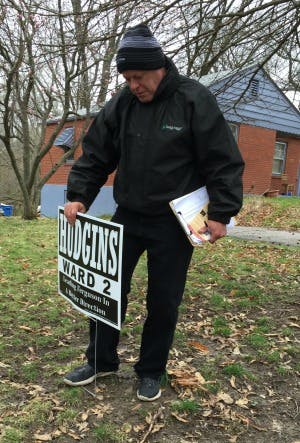

Five days earlier, Bob Hudgins sought to secure Dade Avenue. The underdog Ward 2 candidate had been here earlier in his campaign handing out signs and knocking on doors, but he reserved Friday afternoon to revisit the north-south traffic artery through Ferguson's western edge. We rode up and down the street in his car, which smelled of the ashtray that ranneth over with cigarette butts. A stack of his black-and-white placards lay in his back seat. In Ferguson, even the color of your lawn signs makes a statement.

Hudgins was running against former Ferguson Mayor Brian Fletcher—perhaps the town's most recognizable political figure. The orange Fletcher signs in lawns we passed didn't deter him. “To me, these should be my people. I should be real solid here,” he told me as he set out to canvass a neighborhood. “I have not talked to anybody yet on Dade who said they weren’t voting for me.”

When I met Hudgins he was frank, social, and relentlessly optimistic. But he brought a note of insecurity. He knew who he was up against, for one, but he also spoke with the reserved enthusiasm of someone who loves what he’s doing but isn’t sure he’s doing it well enough. If this City Council race had a salt-of-the-earth Man of the People and protest candidate, Hudgins was it. A former radio broadcaster and baseball blogger, he was at the protest last month in front of the Ferguson Police headquarters—also in Ward 2—when a young gunman opened fire, endangering the demonstrators and wounding two officers. “I heard it, I saw it—I didn’t even want to look,” Hudgins said. “You’re doing this thing where you’re looking out of the corner of your eye. You feel that if you cock your head up, a bullet’s going to fly in your face or something.”

Hudgins, like Fletcher, is a middle-aged white guy. That carried its own meaning in the only Council race without a black candidate, not that Hudgins thought it should have mattered. “Black folks have to learn to deal with white people and consider them as candidates and stuff,” he said during a smoke break on Dade. “I think I’m a better candidate than him, and we’re in a different environment.”

He noted the demographics of the Ward, which like the other two in Ferguson, is majority-black. I ask why local black voters traditionally don’t show up to the polls as much as white voters “It’s generations of people being told they don’t count and not seeing any results,” he said. “Folks are either ignored or intimidated. It’s not apathy. No, no. It’s discouragement, lack of results, generations of discrimination. No matter what they’ve done, they haven’t gotten much for it.”

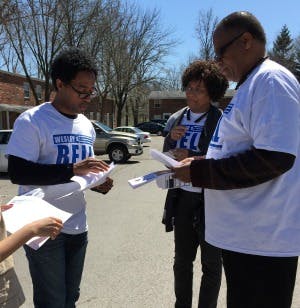

On Saturday, the Wesley Bell automotive cavalry pulled away from his campaign office to West Florissant Road, the principal staging ground of the Ferguson protests. The cars rounded the corner past the burned-out shell of the Qwik Trip gas station to park at the Oakmont Apartments down the street, where the Ward 3 candidate assembled his volunteers. Bell noted a flyer in support of opponent Lee Smith that tried to link Bell with Bob McCulloch—the St. Louis County prosecutor who failed to get Wilson indicted for Brown’s death. Bell took pains with his volunteers, and later with me, to emphasize the positivity of his campaign.

“I don’t think talking down about other people is a platform,” Bell said as we drove in his grey Range Rover to his scheduled door-knocking. “I also don’t think it’s good with respect to building a community and the healing process.” He notes that his field director, a former student of his at St. Louis Community College-Florissant Valley, is also heavily involved in the community. “You know, they can throw all the punches they want,” he said. “I got three older brothers; there’s nothing I haven’t been called.”

This wasn’t Bell’s first go-round. The 40-year-old North St. Louis County native has also run for St. Louis County Council. He learned that accentuating the positive works, but did it almost to a fault when we spoke. Bell notably refused to demand the recall of Mayor James Knowles III, a target of protestors’ venom. He passed up the chance, really, to say anything negative about anyone, including his opponent Smith, a 76-year-old retiree, union veteran, and political neophyte.

Bell pivoted instead to a principal issue of his platform: community-oriented policing. “As a criminal justice professor, that’s one of the things I’ve been preaching for years,” he said. “Community-oriented policing, at its heart, is information going two ways.” Residents should have more input at neighborhood meetings on how they’re policed, he said, and cited other cities’ success in integrating police into community activities such as youth sports. “There’s a science to this,” he said. “I’ve taught an urban policing class—this isn’t something we’re just pulling out of our hats. This has worked in a lot of cities, and it’s going to work right here.”

Ella Jones nearly blew out my eardrums Tuesday night. I had just finished asking her how many butterflies were in her stomach when a campaign volunteer showed her the returns: She’d defeated her three opponents in Ward 1. “AAAAHHH!” she screamed repeatedly, and loudly.

At the black-owned Drake’s Place restaurant, she explained to reporters why she felt she'd won. “When I knocked on the doors and introduced myself to people,” she said, “I told them that I was there to listen to them. Whatever they told me I was going to take back and try to move forward with it. It’s amazing—you can talk to an African American man, 65-years-old, then turn around and talk to a Caucasian man, 65-years-old, and they’re saying the same thing. My job is to be that catalyst so we can come together, and put a new face on Ferguson.”

That will be the case in a literal sense. Jones’ contest was the only one in which the race of the victor was in question. Ferguson’s City Council will now be 50 percent black.

When Bell spoke to reporters after his decisive win over Smith, he had to talk over Kool & The Gang’s “Celebration” playing at a deafening level. “It’s time to work,” Bell told me Tuesday night. “Oftentimes, out of tragedy does come opportunity, and we can’t look back years from now and say, ‘That was an opportunity missed.’ We have a chance to set a broad example of what change can look like.”

That same night Hudgins still longed to be a part of that change. His Election Night party, shared with Smith, was staged at the Ferguson Burger Bar—the only business, I was told, that never closed or boarded up during the August and November protests. “I’m feeling very good,” he told me in the parking lot. “Where I voted, turnout may have been 20 percent, which is eight points higher than a year ago. That has to be good news.”

Increased turnout didn’t portend success for Hudgins. Fletcher easily defeated him, with 30 percent overall turnout—not superlative, but equal nearly to the last three Ferguson elections combined. Hudgins noted the loss in a good-humored tweet Wednesday afternoon:

How the campaign coped: pic.twitter.com/akno23ZzcD

— Bob Hudgins (@Bob_Hudgins) April 8, 2015It remains to be seen whether activists such as Hudgins will make a lasting mark in Ferguson. But anyone who argued that Ferguson was cowed by the brutalization of its citizens or by some alleged apathy no longer has a case.

Diversity on the Council is only one step. The larger question, particularly with Fletcher on the Council, remains just how much the city’s government, policing, and community relations will change in the months and years to come. As Brown's death grows more distant, Ferguson still bears watching.