The list is a long one: of those literary and intellectual dreadnoughts with sketchy personal histories and lifetimes of bad decisions. Not all are equally heinous—Mailer’s drunken wounding of his wife is not Heidegger’s zeal for Hitlerism; Hemingway’s needless butchering of wildlife is not Pound’s radio-wave blustering on behalf of Mussolini—but all are equally condemnable from the cozy perch of posterity. One should not, however, miss an opportunity to point out what some are still in need of hearing: A writer’s personal failings have nothing at all to do with the success or failure of his work.

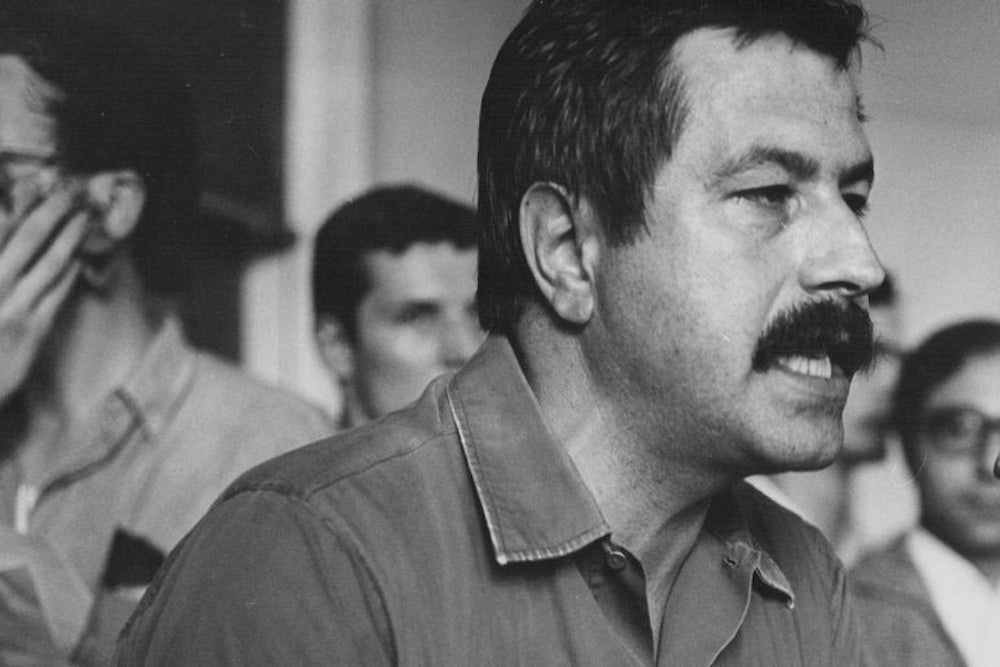

In 2006, prior to the publication of his memoir Beim Hauten der Zwiebel (Peeling the Onion), the German Nobel-Prize winner Günter Grass, who died today at the age of 87, told a newspaper that he’d been a soldier in the Waffen-SS, the sinister Nazi combat force. The admission was a whistle that predictably summoned a phalanx of political and literary foes, since Grass had long before assigned himself the post of Germany’s moral exemplar, the conscience of a country badly in need of a new selfhood.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, as the body count from the Nazi camps continued to soar, Germans were stunned into silence, stomped into shame, and Grass was part of the revolt against tongue-holding and excuse-making. And so his overdue confession of being in Hitler’s Waffen-SS meant, of course, that the famous writer of The Tin Drum, the outspoken authorial face of Germany, was himself guilty of silence—of sanctimony, hypocrisy, and self-promotion in the mask of saintliness.

Peeling the Onion (translated into English by Michael Henry Heim) does much to explain the circumstances of Grass’s wartime past. He never willfully joined the Waffen-SS. He was a boy of 17, not yet man enough for whiskers, befuddled by the din of war, ignorant of what the Waffen-SS really meant, its nefarious history under Himmler.

Grass’s boyish love of boats and his romantic inklings of war had impelled him to leave his impoverished home two years earlier at the age of 15 and enlist in the Luftwaffe auxiliary. He was then drafted into the Waffen-SS after being denied the submarine duty he desperately wanted. Grass had no knowledge that he was a member of an elite killing squad until he soon ended up in the conflagration of Dresden. At that point, the war for Germany was lost. Grass hadn’t fired a single shot.

In his memoir, Grass does offer the rather squirming avowal of having harbored affection for the Fuhrer. He was six years old when Hitler began polluting the airwaves with the mythical, nationalistic agitprop that aimed, among other things, to salve the humiliation Germans suffered after World War I. In its conception and methodology, and in its exploitation of the humiliated, the Third Reich was nothing if not religious and compellingly theatrical. Walter Benjamin once made that point: Fascism is grandiose theater under which citizens willingly suspend their disbelief, because they are gullible, aggrieved, and in need of the promised denouement, yes, but also because they are awed by the spectacle, the pageantry—the uniforms, the music, the monologues. And as every religion knows, they have to get their votaries young, too intellectually defenseless to sniff out the ruse.

Comprehending how a nation can be so thoroughly bamboozled by a dictator’s theatrics remains a fraught enterprise. “To ask the hard question is simple,/ The simple act of a confused will,” Auden wrote. “But the answer/ Is hard and hard to remember.” Grass’s youthful glow for the Fuhrer is not all that hard to grasp, precisely because he was just that: a youth, as impressionable and uncertain as every youth, and of course unaware of Hitler’s genocidal blueprint for European Jewry.

Grass’s adolescent vulnerability was exacerbated by the fact that his father was indifferent toward him—never underestimate the hurt of a boy neglected by his father. One of the most memorable scenes in Peeling the Onion occurs when the 16-year-old Grass returns home on weekend leave and, while lying on the sofa outside his parents’ bedroom, writhes as he listens to them copulating. The same happened to the teenage Kafka: His parents’ lustful moaning drove him mad. For Grass, it was merely a reminder of why he’d left this cramped, unloving home in the first place.

As the revelations accrue, Grass’s memoir becomes a document of one boy’s bewilderment in a time of hemispheric upheaval. The book delves into the mechanisms of memory, and these become Grass’s true theme. “Memory likes to play hide-and-seek, to crawl away,” he writes. “It tends to hold forth, to dress up, often needlessly. Memory contradicts itself; pedant that it is, it will have its way.” Grass’s pestering memory will not relent: “So I write about the disgrace, and the shame limping in its wake.” The old man agonizes over forgiving that feckless 17-year-old boy who couldn’t fire a rifle properly, who spilled jam onto his pants, who didn’t know the fate of his loved ones, who wandered behind Soviet lines and was injured by shrapnel.

The memoir frequently shifts into third person as Grass attempts to gain the proper perspective on his guilt. Some of the most evocative swaths of the narrative are those that detail the hunger and lonesomeness he endured—in a makeshift hospital recovering from wounds, in an American P.O.W. camp after Germany’s defeat, in the unkind, frigid German countryside as he wandered looking for work and for news, unsure if his family had survived the Soviet assault. He would later learn that his parents had indeed survived. Later still, he would learn that goons from the invading Red Army had sexually ravaged his mother. In her lifetime she revealed “nothing that might indicate where and how often she had been raped by Russian soldiers,” and it wasn’t until after her death that Grass learned how she had “offered herself” to the marauders in order to safeguard Grass’s sister. For decades, he could not bear to stand before these facts, “to come out with things long lurking within.”

After Grass’s 2006 disclosure, the accusation-as-question was this: If he was indeed innocent, then why the decades-long silence? Why hadn’t he written about what really happened? In Peeling the Onion, the answer is clear, though no doubt unconvincing to his detractors. He kept quiet not because he was scheming for the Nobel Prize, a futile endeavor any way you cut it, but because he was learning how to forgive himself, learning how to tell the tortured narrative of his youth. John Irving, defending Grass at the time, rightly contended that “good writers write about the important stuff before they blab about it; good writers don’t tell stories before they’ve written them!”

Those conniption critics who pounced on Grass for not writing about the true circumstances of his enlistment—Bernard-Henri Lévy and Christopher Hitchens among them—betrayed a basal misapprehension of how the writer’s psyche actually works, of the crawling consideration a writer needs to turn his roiling past into lasting paragraphs. “It was some time,” Grass writes, “before I came gradually to understand and hesitantly to admit that I had unknowingly… taken part in a crime that did not diminish over the years and for which no statute of limitations would ever apply, a crime that grieves me still.”

In some ways, Grass’s more than 20 published books—the major novels such as The Tin Drum, Cat and Mouse, and Dog Years (collectively called The Danzig Trilogy), but also the plays, the poems, the essays—were prep for the revelations Grass gave us in Peeling the Onion, a kind of fictional, dramatic, and lyrical boot camp that would prime him to divulge the transgressions of his personal history. But of all the things that don’t come easily in life, forgiveness comes least easily of all.

“It is clear,” Grass writes, “I volunteered for active duty. … What I did cannot be put down to youthful folly.” Still, you might want to ask: Who among us wishes to be smeared always for the recklessness and lunacy of our youth? “Youth is a blunder,” wrote Disraeli, and part of the beauty of the world is that most of us get to grow up, to pass beyond those adolescent blunderings, to construct ourselves anew. Grass’s blunder involved him in the most hideous blight of the twentieth century, and for that he shackled himself to shame, though some will continue to say not nearly soon enough.

“What memory stores and preserves in condensed form,” Grass writes in the memoir, “blends with the story in whatever way it is told.” That story—Grass’s own and the story of his work—is, in part, the story of how an artist marshaled national and personal calamity, and made literary monuments that will outshine those modish spotlights on his personal stumbling.

In his introduction to Grass’s On Writing and Politics: 1967-1983, Salman Rushdie got it right when he wrote that Grass’s books “open doors for their readers, doors in the head, doors whose existence they had not previously expected,” and then spoke to Grass’s “capacity for imagining and re-imagining the world.” It is precisely that capacity—the sublime grasp of the imagination, the moral reckoning inherent in the work, in the degree to which the prose can rappel into those unlit recesses of the self—that determines a writer’s worth and worthiness.