If modern feminism is to be believed, women suffer from a lack of confidence relative to men on a whole host of issues, beginning in grade school classrooms and following them into cubicles and corner offices: negotiating salary, speaking up in meetings, hesitating to “lean in” until they’re certain they’ve got the right stuff. Men are freer, more encouraged to believe in their abilities and themselves—or so the thinking goes.

Now, there’s another arena where boldness seems to favor the Y chromosome: The ways we choose to write about the ways we choose to live. Especially if, like the writers Kate Bolick and Fenton Johnson, we’re living large parts of those lives untethered to spouses and children—our autonomy an expanse of possibility ripe for existential musing.

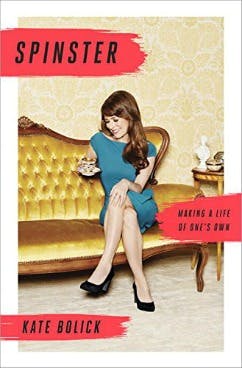

Bolick’s book, Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own, comes out this month. It follows the success of her 2011 Atlantic cover story, “All The Single Ladies,” a meditation on the lives of unmarried women in America that made Bolick a cable show darling and cemented The Atlantic as the must-read magazine for think pieces on “women today.” Bolick called on women to rethink traditional notions about the centrality of marriage in the context of current demographic and economic trends, i.e., the growing enrollment of women in colleges and decline of male enrollment. But where the magazine piece was a positive, data-heavy spin on the “disruption” of the romantic market, Spinster is half-memoir and half-historical examination of the literary women who made their own way and informed Bolick's own path: Now in her early forties, she's lived the writer's life in New York for nearly two decades, opting for romance and possibility over marriage and conventional-style stability.

In last month's Harper's cover story, "Going It Alone," the novelist Fenton Johnson tackles a similar subject. He doesn’t merely examine the societal roles of people living alone, whom he refers to as "solitaries” and defines as those who have “cultivated a special relationship with the great silence.” Instead, Johnson imagines a society where the man or woman alone is ideal, taking for granted that foregoing marriage and childbearing are societally sanctioned life choices. It's difficult not to compare Johnson’s essay to Bolick’s book, as well as with other recent works on the female-heavy “life choices” beat (Meghan Daum’s recent essay collection on childlessness, Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids, is one) by virtue of both their timing and celebrations of single life. Johnson, though, calls for a new world order, whereas Bolick and others are still chewing over and justifying a shifting status quo.

“Why don’t men feel the same need to elaborately justify their romantic lifestyles?” asks Laura Kipnis. She says Bolick is “in quest of validation,” much like Sandra Tsing Loh is in her recent New York piece on solo living (which reads as rage bait for the single urban dweller). “The deeper question about women’s relationship to conventionality might be why it’s apparently a bigger factor for us than for men,” Kipnis says.

There are many possible answers to Kipnis’s question: The idea that women are socialized to believe “you’re born, you grow up, you become a wife,” as Bolick puts it; the relatively recent dominance of women in the professional workforce; and the lingering legacy of blatant mid-century sexism, to name a few. All are troubling. But the answer might simply be due to the confidence gap. Is it a surprise that the more grandiose—and not always careful—visions of a world ruled by autonomous souls are written by men?

Johnson is clear that he does not mean to examine singledom. (He’ll leave that charge up to Bolick and her ilk: “I am not writing about what demographers call ‘singles.’”) For him, it’s a word that means nothing outside the context of marriage. “Nor am I writing about hermits,” Johnson writes. Both Bolick and Johnson make clear that the true subject of inquiry is the nature of solitude and what those who seek it can gain, regardless of marital or romantic status—those “who seek solitude as essential threads in the human weave,” as Johnson puts it. But for Bolick “singles” keep coming up anyway.

Whereas Bolick and many of the writers in Daum’s collection focus on the cultural significance of their personal choices as underscored by demographic trends, Johnson needs no statistics to posit that the solitary life can take the shape of the divine—or at least divine importance. “I am not interested in the possibility that solitaries might lead more carefree lives,” Johnson writes. “My ideal solitary carries not less but more responsibility toward the self and the universe than those who couple.”

In part, this element of the essay is driven by biography. Johnson grew up near a Trappist Abbey in rural Kentucky. He remembers a time when tower bells sounded in the early hours for their prayers, and later witnessing many leave the monastery for secular life—a shift that informed his interest monastic lifestyles: “Does ascetic practice require bricks and mortar?” he wonders. “In our solitude, might we devise ways of supporting and disseminating ascetic virtues without monasteries?” But at times, his piece is almost laughably brazen and overwrought. Johnson invokes spiritual figures—ranging from Siddhartha Gautama to Jesus and Jacob—alongside writers and artists—like Paul Cezanne and Emily Dickinson—as guides for the practice of being solitary. Solitaries who are deities, artists, writers, he says, “possess the key to saving us from ourselves.”

Geoff Dyer, one of the three male contributors to Daum’s collection on childlessness, is so smug he might as well have brought in the Gods, so precious is his choice not to procreate. He gives us colorful scenes of bratty kids bothering him on a tennis court, rattling the cages while their parents stand idly by until his friend yells at the children: “Suddenly, we were in the midst of a maternal zombie film,” he writes. He suggests that parenthood provides an excuse for those who lack bravery to do “that which you would ideally have done”; which is for him, of course, some sort of artistic endeavor. “Parenthood, far from enlarging one’s worldview, results in an appalling form of myopia,” Dyer claims.

Bolick evokes the mystical, too. Her book is organized around her close study of five early and mid-century white, female writers and thinkers she calls her “awakeners”: essayist Maeve Brennan, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, novelist Edith Wharton, columnist Neith Boyce, and activist writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Johnson’s essay is similarly reverential of “the writing life” and its central place in the conversation about aloneness. (Which begs the question: Does one need to be a decorated writer to embrace solitude in a satisfying and societally sanctioned way?) But unlike Bolick and women writing about childlessness in Daum’s collection, Johnson dispenses early with assigning a value judgment to the desire to be alone.

In fact, the Kentucky-born author is not alone by choice. His 1997 memoir, Geography of the Heart, is a story of his love for and the loss of his longtime partner. His aloneness is circumstantial. That’s not only OK; for him, it’s beside the point. “A great deal of virtue is born of necessity,” Johnson writes, saying he wishes to “inhabit” both his solitude and unmarried status—which includes celibacy for an extended period of time—“against all messages of contemporary culture, as a legitimate way of being, an opportunity to focus all that longing on my heart’s desire, whether that be a community garden or world peace.”

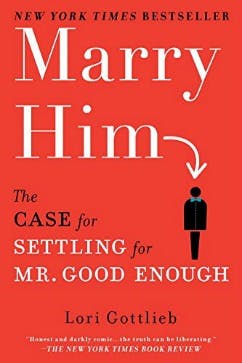

But reconciling twin desires for aloneness and intimacy is the central tension of the modern female “solo living” narrative. Neither Bolick nor any of the writers in Daum’s collection pass judgment on peers making more conventional life choices; Bolick strains to note in her conclusion that anyone can find their “inner Spinster.” Still, there’s a tone of feminist empowerment underlying their work, a pride in the single lady lifestyle, a retort to previous decades of self-help books like The Rules and Marry Him: The Case for Settling For Mr. Good Enough. For the women, then, choosing to forego marriage and/or motherhood is a path to self-actualization. Johnson and Dyer, on the other hand, suggest their life choices are a public service.

“Could solitaries model the choice for reverence over irony? Instead of conquering nations or mountains or outer space, might we set out to conquer our need to conquer?” Johnson wonders. He means the big, real problems: global warming, income inequality, “uncontrolled population growth,” conspicuous consumption. The solitary man or woman can quiet this noise, he suggests. “To choose to be alone is to bait the trap, to create a space the demons cannot resist entering.”

All modern writers on the “aloneness” beat explicitly link solitude to their creative work. (“Being single is like being an artist, not because creating a functional single life is an art form, but because it requires the same close attention to one’s singular needs, as well as the will and focus to fulfill them,” Bolick says.) But they break along gender lines again on the question of what else takes the place of a lifelong partnership or offspring.

Both Bolick and Johnson do point out the obvious truth that, for the long-term singleton, friends and nuclear family bonds become crucial, providing the emotional sustenance one might find in a romantic coupling. But only Bolick acknowledges (albeit too briefly) the reality, that while marriage and children are still pervasive cultural norms, friendships wax and wane in their capacity for fulfillment.

“Even the close friends I’d made in New York were ‘joining the vast majority,’” Bolick writes of a period between boyfriends and jobs in her mid-thirties, noting that her life’s trajectory had put her out of sync with her peers. “All of us wanted to believe this wouldn’t change anything,” Bolick writes. “But it did, variably, in ways small and large.”

Yet Johnson concludes his piece by calling for a radical reversal after decades of living in a culture that rewards coupledom, arguing that friendship should take its place as “the queen of virtues” and “the foundation for all worthy connection, including marriage.” He offers few suggestions for how we get to this place of holy friendship or what it might look like.

“My vision is no more fantastic than colonies on Mars, solar grids in space, heat transfer from the oceans, impregnable vaults for nuclear waste, carbon-dioxide storage under the Great Plains or any of hundreds of proposals our politicians and research institutions and media take seriously,” he insists.

However outlandish that may sound, it’s confident. No one is going to interrupt that in a meeting. It might even get him a raise. The women who write about solitude are only just beginning to lean in to that conversation.