If Mitt Romney had defeated President Barack Obama in the 2012 election, a lot of things would be very different today. Had fortunes been so reversed, Romney would likely have come into office with a lock on Congress, and thus the power to pass a big tax cut and repeal (or at least hobble) the Affordable Care Act. When the economy improved and unemployment fell below six percent much earlier than Romney promised, Republicans would have claimed credit and Romney would have faced an easy path to re-election.

Romney's successes—or his perceived successes—would have rehabilitated the Republican party’s reputation, and the public would have once again presumed that conservatives had effective ideas about economic and fiscal policy. The New Deal consensus would have dwindled, possibly enough for Republicans to shrink, devolve, or privatize parts of the safety net. With time on their side, conservatives would have looked forward to gaining decisive control over the Supreme Court for a generation.

The first black president of the U.S. would have left office humiliated by a white electorate, and the Democratic Party would have regressed, fearful that the country would not stand for long behind minority political leaders, and progressive social policy.

With these stakes clear to everyone who watched Republicans sweep the 2010 midterms, Politico nevertheless argued in the summer of 2012 that, “Dating to the beginning of the cycle, 2012 has unfolded so far as a grinding, joyless slog, falling short in every respect of the larger-than-life personalities and debates of the 2008 campaign.”

As candidates discover new ways of communicating to voters, and campaigns become correspondingly more insular, P.R. driven, and insolicitous of the press, this has become a familiar complaint. It’s also a self-fulfilling one, as George Packer illustrates in his latest New Yorker article.

“[T]he 2016 campaign doesn’t seem like fun to me. Watching Marco Rubio try to overcome his past support for immigration reform to win enough conservative votes to become the Mainstream Alternative to the Invisible Primary Leader—who, if there is one, will be a candidate named Bush—doesn’t seem like fun,” Packer writes. “Nor does analyzing whether Chris Christie can become something more than the Factional Favorite of moderate Republicans, or whether Ted Cruz’s impressive early fundraising will make him that rare thing, a Factional Favorite with an outside chance to win.”

A year of covering the 2016 race like this would fossilize my soul, and reading a year’s worth of analysis like this will drain all the precious fluids from my eyeballs. But to argue that 2016 will be boring because campaign reporting conventions are boring is to drain oneself of agency. In fact, Packer could liberate himself from the specter of watching 2016 through the prism of those reporting conventions by simply following his own advice.

“The issues remain huge and urgent,” Packer writes, before launching into a list of eight things that would liven the next year and a half. Six of them are genuinely fantastical, but the last two?

7. Political reporters should embrace the value of objective truth, and adopt a policy of never repeating a party or a candidate’s dubious or false statement without exposing it in the next sentence.8. Policies and their consequences should be the main story, tactics the footnote. Coverage of a candidate’s positioning on this or that issue should include a reminder of the context: notwithstanding No. 6 above, the differences between the two parties are clear, stark, and uniform across almost all issues.

It is entirely within Packer’s power to conceive of and cover the 2016 campaign in this way, rather than conceiving of it as the sum of the worst journalism it inspires. If you place this election in its proper political and historical contexts, it’s insanely interesting, and has stakes that rival (though don’t quite match) those of 2012.

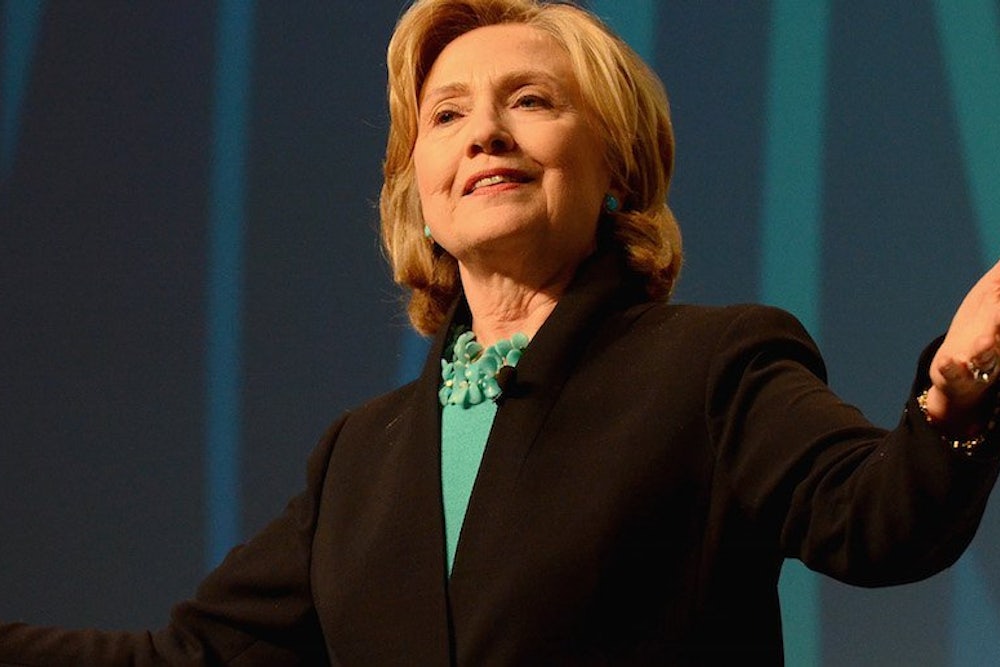

Because Republicans will maintain control of the House of Representatives under almost any circumstances, and because her regulatory agenda would resemble Obama’s, a Hillary Clinton victory wouldn’t be a liberal policy watershed like Obama’s was. But it would be momentous in other ways—most obviously for women’s leadership and as a ratification of America’s comfort with electing non-white-males generally—not recoiling from Obama’s presidency back into the old white guy pattern. Her victory would make Obama’s reorientation of the Democratic party semi-permanent, much as George H.W. Bush’s election in 1988 crystalized Ronald Reagan in the Republican imagination.

Clinton would very likely be able to flip the ideological balance of the Supreme Court, and with successful leadership could ultimately help end the GOP's vicelike grip on Congress.

A Republican president, by contrast, would enjoy immediate legislative and regulatory dividends. After cutting taxes, a Republican president would be able to do great damage to Obama’s legacy. Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz’s candidacies carry with them the possibility of the country’s first Latino president succeeding its first African American one. In eight years time, a Republican president would leave behind a Supreme Court tilted heavily to the right, with a durable 6-3, or possibly 7-2, conservative majority.

The candidates themselves won’t lay out the stakes this nakedly, but this is what they’ll be trying to communicate by repeating platitudes that understandably make reporters yawn. “The language of politics stays the same, and it is a dead language,” Packer wrote. Sometimes it feels that way. But people who know how to translate from dead languages into living ones have supplied us with some of our most basic and crucial knowledge.