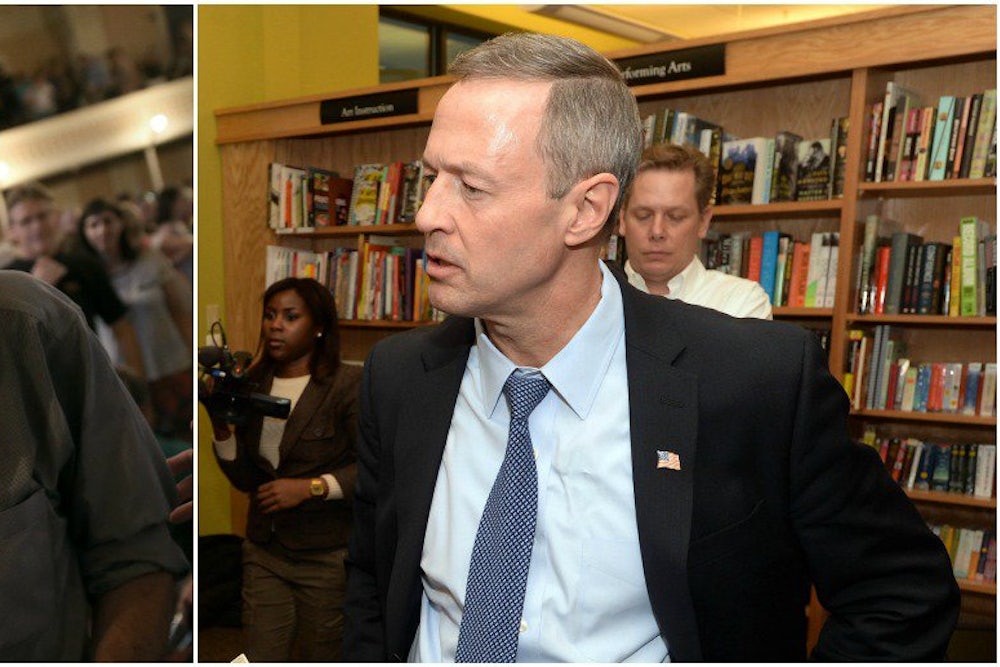

Martin O’Malley has checked enough boxes as a prominent Democrat—big city mayor, mostly successful governor, chairman of the Democratic Governor’s Association—that he probably didn’t expect to be trailing in presidential polls to a Vermont senator who serves as an independent and identifies as a democratic socialist. But for now he does trail, and pretty badly. O’Malley is more dependably liberal than Hillary Clinton has been, but the emergence of a crusading progressive like Bernie Sanders has convinced some analysts that O’Malley miscalculated, and let Sanders steal his thunder.

“Late to the dance,” as one strategist told The Hill, and presumably he’s pissed off about it. You might suppose that O’Malley harbors frustration not just with Hillary Clinton, for the immensity of her lead, but also with Sanders, who, if the field stays narrow, will skim support from left-wing Democrats that might otherwise back him in a one-on-one matchup between Democratic establishmentarians.

But if that’s true, which it may not be, it’s because O’Malley has fundamentally misread the status quo in Democratic politics, and imagines a potential parallel between the 2008 and 2016 elections that doesn’t exist at the moment.

If this election cycle were anything like the one that vaulted Barack Obama to the Democratic nomination O’Malley wouldn’t be polling at less than two percent. The former Maryland governor, who is expected to announce his candidacy on Saturday, is at least as credentialed to be president as anyone who ran in that field, or anyone in the Republican primary field that’s taking shape today. In a different milieu, he’d be harder to write off than, say, Ben Carson, who despite being an extreme and eccentric candidate has about four times as much support among Republican primary voters as O’Malley does among Democrats.

But in the current Democratic milieu—if RealClearPolitics’ poll averages are any indication—O’Malley looks dead in the water. Separating him and Clinton, who dominates today’s Democratic field with over 60 percent support, are Senator Elizabeth Warren, who commands 12.5 percent despite not being a candidate; Vice President Joe Biden, another non-candidate, with 9.8; Sanders, 7.4; former U.S. Senator Jim Webb, who is exploring a run, 2.6 percent; and, embarrassingly enough, former Rhode Island Governor Lincoln Chafee, who edges out O’Malley 1.5-1.2.

Hillary Clinton was also the frontrunner in 2008, of course, but a mix of factors that no longer prevails exposed her to viable challenges and ultimately defeat. The Iraq war, which initially divided the Democratic Party, quite correctly came to be seen as the Bush administration’s cardinal sin. Not only did Clinton vote to authorize the war, but she had a more difficult time than other early supporters disavowing it. And while she enjoyed tremendous name recognition, she was still a relatively junior senator. This simultaneously exposed her to criticism from more experienced contenders, and made her central criticism of Obama ring hollow.

Now, her heresies and inexperience are ancient history. Clinton has padded her resume with a four-year stint as secretary of state, and today, no issue divides Democratic politicians and galvanizes Democratic primary voters quite like the Iraq war once did; the Trans-Pacific Partnership is about as close as it comes (which is to say, not very close). In any party, there’s usually an appetite for an outsider to challenge the establishment, but this year there doesn’t seem to be much hunger for a different establishmentarian to supersede the frontrunner. Sanders isn’t crowding O’Malley out; Hillary Clinton is. As Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid recently proclaimed, “There’s not another Barack Obama out there … no all-stars out there” to challenge Clinton.

That may or may not be true, but it doesn’t account for the fact that there’s no vacuum for such an all-star to fill. And if O’Malley’s as pragmatic and data-driven as he portrays himself to be, he should be just fine with that.

If Clinton, 67, wins the presidency and serves two terms, O’Malley will still be younger at that point than she is right now. At 52, he has enough life ahead of him to embark on an entirely new career, or bide his time until he can run again in eight years. Spending the better part of a year trying to damage Clinton and marginalize Sanders isn’t a wise path toward the latter.

I expect O’Malley’s share of the Democratic vote to rise somewhat between now and the primaries, but Clinton currently trounces the rest of the field combined, and Sanders and O’Malley’s total share may never eclipse Clinton’s. In the face of such daunting odds, O’Malley’s best bet isn’t to throw bombs, but to burnish his brand as the kind of candidate who’d be an ideal frontrunner—if it weren’t for the Clinton phenomenon. If Clinton’s candidacy combusts unexpectedly, the Democratic establishment isn’t going to rally around Sanders or a Sanders wannabe; they’ll rally around O’Malley or someone like him. And if Clinton wins the presidency, his path to eventual power will run through staying in her good graces (and may include a stop inside the Clinton administration).

O’Malley pitches himself as a cooly strategic politician. If indeed that’s true, we can expect him not to make himself the focal point of controversy. And that’s something he’s so far excelled at.