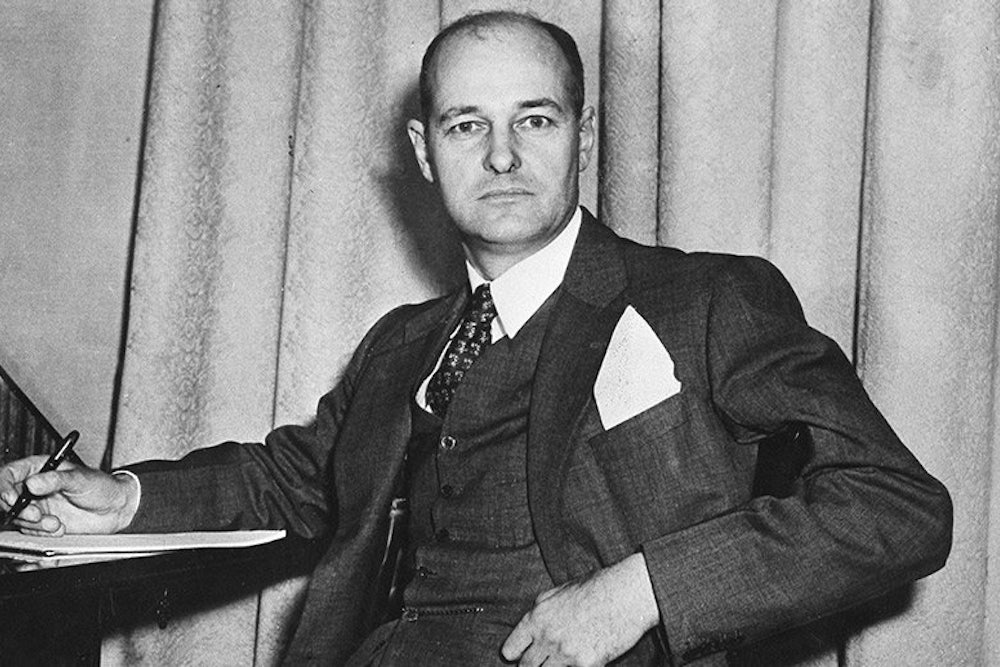

Has there ever been an American diplomat as revered as George Kennan? Kennan was often celebrated as the wisest of the Wise Men, the prescient seer who offered his country prudent counsel during a century-spanning life—most famously, the strategy of containment that would govern American policy until the demise of the USSR. Testimonies to Kennan’s sagacity could be found on all sides of the political spectrum: The liberal historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. described the one-time ambassador to the Soviet Union as “indisputably an American sage” while his conservative counterpart John Lukacs lauded the diplomat as “a visionary and a prophet.” In 2004, during an event celebrating Kennan’s hundredth birthday, then Secretary of State Colin Powell hailed the centenarian as “our best tutor, our inspiration.” Other Cold Warriors like John Foster Dulles or Robert McNamara have been excoriated for their belligerence and blundering; Kennan has been widely admired for laying out a moderate foreign policy that sought to curb Soviet ambitions but avoid needless bloodshed or the risk of nuclear war.

Among the many surprises of Perry Anderson’s determinedly revisionist new book, American Foreign Policy and Its Thinkers, is that it completely demolishes the myth of Kennan as a wise oracle. Far from being “a sober adviser whose counsels of moderation and wisdom,” Kennan, Anderson argues, was “unstable and excitable,” a “Cold Warrior” to the extreme, and “closer to a character out of Dostoevsky than any figure in Chekhov, with whom he claimed an affinity.” Not at all like the cool, sometimes paralyzed characters in Chekhov, Kennan had a veritably Dostoevskian tendency to adopt extreme positions.

To support his debunking of Kennan, Anderson sprinkles his book with jarring quotes. In 1927, Kennan described the Bolsheviks as “a little group of spiteful Jewish parasites.” On the cusp of World War II, Kennan contended that immigrants, women, and blacks should be disenfranchised. In 1947, Kennan argued that America “would be justified in considering a preventive war” against the Soviets, “with probably ten good hits with atomic bombs you could, without any great loss of life or loss of the prestige or reputation of the United States, practically cripple Russia’s war-making potential.” In 1948, he advocated outlawing the Italian Communist Party on the eve of elections in that country, arguing that although this move would “admittedly result in much violence and probably a military division of Italy,” it was still preferable “to a bloodless election victory” for the communists. (In actuality, the communists were defeated in a free election, albeit one marred by corruption.) In 1949, Kennan called on American intervention to “to ensure, however long it takes, the triumph of Indochinese nationalism over Red imperialism”—one of the earliest articulations of the principles that led to the Vietnam war.

It wasn’t just a matter of rhetoric. Kennan’s words had real impact, Anderson shows, especially in regards to American policies toward propping up right-wing dictators in the developing world. And in his less vocal positions, he aligned himself with some of the more unsavory characters of American history. In the 1960s and ’70s, alarmed by the anti-war movement and the black power movement, Kennan did extensive counter-subversion work in collaboration with one of J. Edgar Hoover’s most repugnant associates at the FBI, William Sullivan, the man who oversaw the wiretapping of Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1971, Kennan urged laws changed so that anti-war protestors and black radicals could be jailed for their opinions. In 1979, Kennan wanted America to declare war on Iran.

Anderson has a point to make and in that effort, he can overweigh one side of the record, giving scant acknowledgment to the occasions when Kennan did live up to his reputation for foresight and prudence. One could point to Kennan’s calls for the demilitarization of Germany and Austria in the 1950s, his late-life criticisms of the arms race, and his disdain for George W. Bush’s Middle East adventurism, for instance. Kennan’s elegant historical scholarship deserves more attention than the admiring glance given by a footnote in Anderson’s book. But praise for the judicious Kennan has been sung time and again, so Anderson’s book stands as a deliberate heckling of a choir that has become too complacent.

This treatment of Kennan serves as microcosm for Anderson's book’s larger approach. Anderson is using Kennan as a barometer for the American foreign-policy-making elite, a community more given to mutual praise than self-critical analysis. As Anderson argues, Kennan’s “actual record—violent and erratic into his mid-seventies—serves as a marker” for what was considered acceptable by the foreign policy elite. The inability of many panegyrists to honestly confront the more sordid side of Kennan’s record testifies to a journalistic and scholarly discourse that flinches from reality. That discourse is as much Anderson’s subject as the record of diplomats like Kennan.

As one of the world’s leading Marxist historians and the longtime editor behind the scholarly journal the New Left Review, Anderson naturally approaches American foreign policy with an outsider’s eye, seeing patterns that are less visible to those who live inside the system. But this doesn’t mean the book is totally denunciatory. Anderson has always been the sort of Marxist who prefers cool analysis to emotional outrage. As an analyst he’s often evoked Antonio Gramsci’s famous slogan, "pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will" (which Gramsci himself derived from the French novelist Romain Rolland).

If Anderson has a fault, it’s that the severity of his pessimistic intellect overrides any possibility of an optimistic hope of rebellion. Anderson has very little faith the revolution is coming around anytime soon. Like his previous works, the vast bulk of Anderson’s new book deals with the thoughts and activities of elites. He nods toward the fact that the agenda promoted by elite foreign policy circles has always had popular opposition, but he thinks such dissenting voices have had a negligible historical impact. The major leftist historians of the last generation—notably E.P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, and Natalie Zemon Davis—celebrated the ability of social movements to remake the world. Anderson’s version of history concentrates on the robustness of elite domination.

Anderson’s book is divided into two: The first half is a mountain-top survey of American foreign policy from the birth of the Republic to Obama, with most attention given to the last century after America emerged as the heartland of global capitalism. The pivotal point of this narrative is the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, during which America became a global hegemon. The crises of this era—both the persistent economic turmoil and the rise of expansionist dictators—called America to self-consciously take on the role of capitalism defender—protecting it through both the promotion of free trade and military alliances (such as NATO).

The second half of the book profiles the highbrow pundits whose books on grand strategy tend to inform elite understanding of the world, figures like Walter Russell Mead, Michael Mandelbaum, John Ikenberry, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Francis Fukuyama. By Anderson’s account, these policy-makers—and the rest of the relatively small and coherent policy-making elite made up of career bureaucrats, investment bankers, lawyers, and academics—are constantly concerned not only with America’s national security but also the health of American business and the need to shape a global order where the American version of capitalism can thrive. This emphasis on economics as primary owes much to the now unfashionable work of mid-century historians like William Appleman Williams. As Anderson rightly notes, contemporary diplomatic historians shy away from the frank discussion of economic motives found in Williams, but there can be no full understanding of American foreign policy without an acknowledgement of Williams’s insights.

Anderson very much respects, in the manner of a watchful enemy, the practice of American foreign policy. He doesn’t whitewash any of the crimes of America, but he does see foreign policy as being guided by a rational elite that has, on the whole, an astute understanding of how to defend the interest of both national and global capital (even as the two occasionally diverge).

Yet the intellectual caliber of the theorists and apologists—the Mandelbaums, Ikenberrys, and Brezezinskis of the world—is disappointing. Kennan, as we’ve seen, was shrill and unstable. His modern counterparts are scarcely better. The esteemed historian and Kennan biographer John Lewis Gaddis once argued the career of George W. Bush was “one of the most surprising transformations of an underrated national leader since Prince Hal became Henry V.” In a recent book, Zbigniew Brzezinski proposed a scheme whereby “European youth could repopulate and dynamize Siberia.”

As Anderson rightly notes, foreign policy books are often littered with blueprints of a “fantastical nature”: “Gigantic rearrangements of the chessboards of Eurasia, vast countries moved like so many castles or pawns across it; elongations of NATO to the Bering Straits; the PLA patrolling the derricks of Aramco; Leagues of Democracy sporting Mubarak and Ben Ali; a Zollverein from Moldova to Oregon, if not to Kobe; the End of History as the Peace of God.” How do we reconcile such foolishness from an elite that has, over the last century, with mistakes here and there, constantly displayed a cagey understanding of how the world works? Anderson suggests these fantasies might betray fears that America’s global hegemony is about to wane.

But this idea doesn’t quite jibe with Anderson’s own cogent account of the continuing resilience of American power, and Anderson sharply rebukes those on the left who believe American hegemony “is in steepening decline, if not terminal crisis.” As Anderson rightly notes, “radical opposition to the American empire, however, does not require reassurance of its impending collapse or retreat.” There is an unreconciled contradiction in Anderson’s own mind about just how dire the prospects are for long-term American global dominance.

Like everything Anderson writes, American Foreign Policy and Its Thinkers deserves careful reading. He’s one of the world’s great historians, unrivalled in his ability to master and synthesize vast historical literatures (often drawing on many languages). Yet in this volume, Anderson’s daunting erudition doesn’t quite encompass the fullness of the topic. This book calls out for a sequel, one that addresses more squarely the prospects of American power in the new century and the shape of the possibly post-American future.