In May of 1870, one dozen members of the Ku Klux Klan lured North Carolina State Senator J.W. Stephens into the basement of the local courthouse, where they stabbed him to death. His murder came only months after North Carolina’s governor summoned the state militia to protect citizens from “persons masked and armed” inflicting a “constant state of terror.”

According to statements and depositions submitted to the governor’s office between 1869 and 1871, the Klan committed hundreds of barbaric acts across the state during that time, including kidnapping five men in Lenoir County, slashing their throats and throwing their bodies into the Neuse River; murdering the sheriff of Jones County in broad daylight; clubbing a woman to death in Pittsboro; publically drowning a woman for insulting a white lady; and kidnapping a young boy from his father at midnight, lynching him, and leaving his body to hang until it was picked apart by vultures.

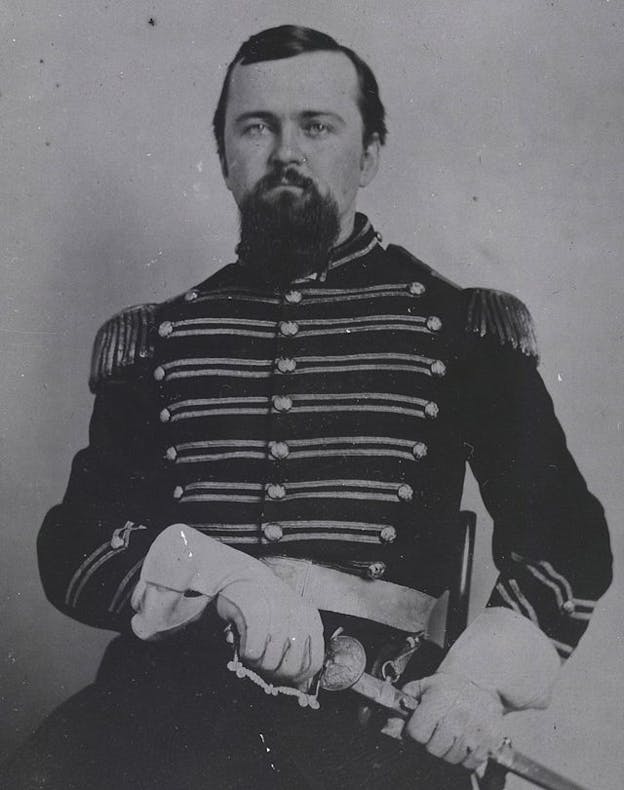

As chief organizer of the North Carolina Klan during that time, William Laurence Saunders was nothing less than a domestic terrorist. Saunders and his fellow Klansmen used violence and murder to overthrow the state’s government and intimidate black citizens from voting or holding office.

When confronted about his ties to the Klan, Saunders became the first man in America to invoke his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. His repeated response, “I decline to answer,” was carved onto his tombstone, along with the sentence, “For 20 years he exerted more power in North Carolina than any other man.”

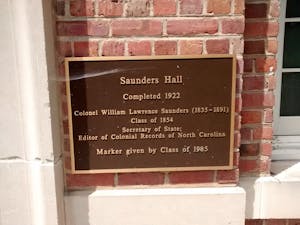

Thirty years after his death, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill named a building after him. Rather than condemning the hateful legacy of the 1854 graduate, the university celebrated his service as a confederate colonel, as state secretary of state, and as “Head of the Ku Klux Klan.” For 93 years, Saunders Hall stood at the heart of the oldest public university in the country, a concrete tribute to North Carolina’s history of white supremacy.

On May 28, the university’s Board of Trustees voted to change the name. But as the process that led to the change shows, the university hardly silenced its critics.

Efforts to rename Saunders Hall date back to the 1970s; in 1999, when several students learned about the building’s history, they draped the building with nooses. In 2001, a campus group called The Freedom Legacy Project demanded a plaque contextualizing his subversive past.

Ignored by administrators and overlooked by the student population, the issue receded until the winter of 2014 when university trustee Alston Gardner read a profile of The Real Silent Sam Coalition in the university’s Daily Tar Heel newspaper; Real Silent Sam is a network of campus activists formed in 2011 in an attempt to contextualize Silent Sam, a statue honoring 321 alumni who died in the Civil War that was dedicated with a speech calling the monument “a win for the Anglo-Saxon race.”

Gardner had coffee with coalition members, encouraging them to bring their issues before the board. An online petition to rename Saunders received more than 800 signatures and was presented to the board in May of last year. A year of deliberation and direct action followed.

“We’re trying to show that spaces of higher education were sites of white supremacy,” said Nikhil Umesh, a former Daily Tar Heel staff writer and recent graduate who became heavily involved with Real Silent Sam. “Challenging racialized geography is an important way to shed light on how institutions are complicit in racism. Higher education is not a utopia, and building names matter because who we honor matters.”

Last year, Duke University renamed Aycock Residence Hall, originally named for former North Carolina governor Charles Aycock, who openly espoused white supremacist views. UNC-CH has its own Aycock Hall, one of several buildings (and even an avenue) on campus dedicated to figures with ties to slavery or white supremacy.

But Saunders remained still the primary target of activists. In late January of this year, Real Silent Sam organized over 500 students for a rally to #KickOutTheKKK, where speakers expressed their demands, including renaming Saunders after Zora Neale Hurston, the noted black folklorist and author of Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Changing Saunders to Hurston was the rallying cry. “The idea of ‘Hurston Hall’ came from black women here at UNC,” says Ishmael Bishop, a rising senior. “The complete opposite of Saunders, and his mission, was this black woman pursuing her education here in the 1930s.” But UNC officials were skeptical of the Hurston name. Once on the faculty of nearby North Carolina Central University, Hurston supposedly sat in on a couple classes taught by UNC playwright Paul Green, but there’s no record. “There’s no evidence she was ever a student at UNC,” Gardner told me. Another replacement name considered was Karen Parker, the first African American woman officially enrolled at UNC.

One month later, a dozen female black students gathered on the steps of Saunders for three hours wearing nooses around their necks. “This is what Saunders would do to me,” read one of their signs, “Black Lives Matter,” read another. A week later, Hurston received 403 write-in votes for student body president, inspiring the newly elected president to make renaming Saunders a priority.

Meanwhile, the trustees asked for input, ultimately speaking to 250 people, from students and faculty to consultants and the historian Taylor Branch. Board secretary Sallie Shuping-Russell remembered that records of trustee meetings existed back to 1789; so Gardner and fellow trustee Charles Duckett dug through the archives of Wilson Library, finding the minutes of the 1920 board of trustees meeting listing Saunders’ KKK leadership as an accolade. “It was pretty damming,” says Gardner. “It was the smoking gun.”

According to UNC policy, a building may be renamed “If the benefactor’s or honoree’s reputation changes substantially so that the continued use of that name may compromise the public trust, dishonor the University’s standards or otherwise be contrary to the best interests of the University,” but it cautions against alterations “because later observers would make different judgments.”

Edwin M. Yoder, Jr., a former editor of the Daily Tar Heel from 1955-56, submitted a letter to the editor offering that the KKK’s actions, taken, “even at their worst, historically conditioned relationships, following a bloody fraternal war, do not justify historical vandalism.” Additionally, there was reluctance from black professors and community members to change the name, preferring instead to educate students about the history. But Saunders Hall was unacceptable. The only connection between Saunders and the trustees in 1920 was a resurgence of the Klan. “They dedicated a building after Saunders to rehabilitate the name and image of the Klan,” says Gardner.

This past March, Gardner and Duckett released a report, and students packed the audience holding up cardboard signs reading “Racism Kills” and “BOT, value ALL of your students.” The board created a website for student comments. Of the 212 postings, 183 supported a renaming, to 25 opposed. Change was inevitable, but not the outcome.

On the last day of class in April, instead of partying, Real Silent Sam members unveiled the banner “Hurston Hall” over the front of Saunders. After 93 years, students wanted a black woman to be its future. But after thirty minutes of discussion, the trustees voted 10-3 to rename Saunders Hall as Carolina Hall. A settlement suggested by a member of Chancellor Carol Folt’s cabinet. “They didn’t want to make it about another person, just about Saunders,” says Gardner. Hurston’s name was never mentioned in the meeting.

Two other resolutions passed unanimously. The first to place a 16-year freeze on the renaming of all campus buildings, monuments, memorials and landscapes; the second to create historical markers for Saunders Hall and Silent Sam, and implement an orientation program detailing the school’s history on race.

The freeze was a compromise to get votes for renaming Saunders. “Their concern was spending the next ten years looking at every single building on campus,” says Gardner of the board. The plaque outside Carolina Hall will include the words: “We honor and remember all those who have suffered injustices at the hands of those who deny them life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

To university administrators, it was a victory for unity and student engagement. To some of the students, it was a half-measure, if not betrayal. “They made that site neutral,” says Omololu Babatunde, a Real Silent Sam organizer who attended classes in Saunders. “Saunders Hall was never neutral. There needs to be a certain person on that site.”

The statement released by Real Silent Sam the day after the renaming called Carolina Hall “a sugar-coating of Saunders Hall updated for the aesthetics of a 21st-century white supremacy color blindness and multicultural diversity. This isn’t justice, it’s pageantry.”

“Every member of the Board rejected the opportunity to address invisibility of black and brown students and our histories,” the statement continued. “[T]he 16-year moratorium on renaming historic buildings and monuments is a lazy attempt to extinguish the anti-racist social movement on our campus, nothing more.”

The movement to rename Saunders was never about Hurston, and it was not about Saunders, it was about empowering students of color and legitimizing their humanity. The University of North Carolina was founded as a university of the people; but for the better part of 221 years, only whites were allowed to attend. On homecoming Saturday last October, black students marched from the Old Well to Kenan Memorial Stadium chanting, “UNC was established for white men/Can you see us now/UNC students have changed.”

In the end, recognizing the value of those students will require more than a cultural center or a field of study. “If the board had respected the wishes of the coalition and the work done this year, by renaming the building Hurston Hall, it would have been a moment of priority for students of color, especially black women,” says Bishop. But nothing changed, except the name on the building.

Ultimately, it’s up to the students to decide what Saunders gets called, because they are the ones who will use it. “Carolina Hall sounds whitewashed,” says Charity Watkins, a graduate student involved with Real Silent Sam. “In my eyes, it will always be Hurston Hall.”