Over the last four years I have been sent letters from strangers caught in doomed, desperate marriages because of repressed homosexuality and witnessed several thousand virtually naked, muscle-bound men dance for hours in the middle of New York City, in the middle of the day. I have lain down on top of a dying friend to restrain his hundred-pound body as it violently shook with the death-throes of AIDS and listened to soldiers equate the existence of homosexuals in the military with the dissolution of the meaning of the United States. I have openly discussed my sexuality on a television talk show and sat on the porch of an apartment building in downtown D.C. with an arm around a male friend and watched as a dozen cars in a half hour slowed to hurl abuse. I have seen mass advertising explicitly cater to an openly gay audience and watched my own father break down and weep at the declaration of his son’s sexuality.

These different experiences of homosexuality are not new, of course. But that they can now be experienced within one life (and that you are now reading about them) is new. The cultural categories and social departments into which we once successfully consigned sexuality—departments that helped us avoid the anger and honesty with which we are now confronted—have begun to collapse. Where once there were patterns of discreet and discrete behavior to follow, there is now only an unnerving confusion of roles and identities. Where once there was only the unmentionable, there are now only the unavoidable: gays, “queers,” homosexuals, closet cases, bisexuals, the “out” and the “in,” paraded for every heterosexual to see. As the straight world has been confronted with this, it has found itself reaching for a response: embarrassment, tolerance, fear, violence, oversensitivity, recognition. When Sam Nunn conducts hearings, he knows there is no common discourse in which he can now speak, that even the words he uses will betray worlds of conflicting experience and anxieties. Yet speak he must. In place of the silence that once encased the lives of homosexuals, there is now a loud argument. And there is no easy going back.

This fracturing of discourse is more than a cultural problem; it is a political problem. Without at least some common ground, no effective compromise to the homosexual question will be possible. Matters may be resolved, as they have been in the case of abortion, by a stand-off in the forces of cultural war. But unless we begin to discuss this subject with a degree of restraint and reason, the visceral unpleasantness that exploded earlier this year will dog the question of homosexuality for a long time to come, intensifying the anxieties that politics is supposed to relieve.

There are as many politics of homosexuality as there are words for it, and not all of them contain reason. And it is harder perhaps in this passionate area than in any other to separate a wish from an argument, a desire from a denial. Nevertheless, without such an effort, no true politics of sexuality can emerge. And besides, there are some discernible patterns, some sketches of political theory that have begun to emerge with clarity. I will discuss here only four, but four that encompass a reasonable span of possible arguments. Each has a separate analysis of sexuality and a distinct solution to the problem of gay-straight relations. Perhaps no person belongs in any single category; and they are by no means exclusive of one another. What follows is a brief description of each: why each is riven by internal and external conflict; and why none, finally, works.

I.

The first I’ll call, for the sake of argument, the conservative politics of sexuality. Its view of homosexuality is as dark as it is popular as it is unfashionable. It informs much of the opposition to allowing openly gay men and women to serve in the military and can be heard in living rooms, churches, bars and computer bulletin boards across America. It is found in most of the families in which homosexuals grow up and critically frames many homosexuals’ view of their own identity. Its fundamental assertion is that homosexuality as such does not properly exist. Homosexual behavior is aberrant activity, either on the part of heterosexuals intent on subverting traditional society or by people who are prey to psychological, emotional or sexual dysfunction.

For adherents to the conservative politics of sexuality, therefore, the homosexual question concerns everyone. It cannot be dismissed merely as an affliction of the individual but is rather one that afflicts society at large. Since society depends on the rearing of a healthy future generation, the existence of homosexuals is a grave problem. People who would otherwise be living productive and socially beneficial lives are diverted by homosexuality into unhappiness and sterility, and they may seek, in their bleak attempts at solace, to persuade others to join them. Two gerundives cling to this view of homosexuals: practicing and proselytizing. And both are habitually uttered with a mixture of pity and disgust.

The politics that springs out of this view of homosexuality has two essential parts: With the depraved, it must punish; with the sick, it must cure. There are, of course, degrees to which these two activities can be promoted. The recent practice in modern liberal democracies of imprisoning homosexuals or subjecting them to psychological or physiological “cures” is a good deal less repressive than the camps for homosexuals in Castro’s Cuba, the spasmodic attempt at annihilation in Nazi Germany or the brutality of modern Islamic states. And the sporadic entrapment of gay men in public restrooms or parks is a good deal less repressive than the systematic hunting down and discharging of homosexuals that we require of our armed forces. But the differences are matters of degree rather than of kind; and the essential characteristic of the conservative politics of homosexuality is that it pursues the logic of repression. Not for conservatives the hypocrisy of those who tolerate homosexuality in private and abhor it in public. They seek rather to grapple with the issue directly and to sustain the carapace of public condemnation and legal sanction that can keep the dark presence of homosexuality at bay.

This is not a distant politics. In twenty-four states sodomy is still illegal, and the constitutionality of these statutes was recently upheld by the Supreme Court. Much of the Republican Party supports this politics with varying degrees of sympathy for the victims of the affliction. The Houston convention was replete with jokes by speaker Patrick Buchanan that implicitly affirmed this view. Banners held aloft by delegates asserted “Family Rights For Ever, Gay Rights Never,” implying a direct trade-off between tolerating homosexuals and maintaining the traditional family.

In its crudest and most politically dismissible forms, this politics invokes biblical revelation to make its civic claims. But in its subtler form, it draws strength from the natural law tradition, which, for all its failings, is a resilient pillar of Western thought. Following a Thomist argument, conservatives argue that the natural function of sexuality is clearly procreative; and that all expressions of it outside procreation destroy human beings’ potential for full and healthy development. Homosexuality—far from being natural—is clearly a perversion of, or turning away from, the legitimate and healthy growth of the human person.

Perhaps the least helpful element in the current debate is the assertion that this politics is simply bigotry. It isn’t. Many bigots may, of course, support it, and by bigots I mean those whose “visceral recoil” from homosexuals (to quote Buchanan) expresses itself in thuggery and name-calling. But there are some who don’t support anti-gay violence and who sincerely believe discouragement of homosexuality by law and “curing” homosexuals is in the best interest of everybody.

Nevertheless, this politics suffers from an increasingly acute internal contradiction and an irresistible external development. It is damaged, first, by the growing evidence that homosexuality does in fact exist as an identifiable and involuntary characteristic of some people, and that these people do not as a matter of course suffer from moral or psychological dysfunction; that it is, in other words, as close to “natural” as any human condition can be. New data about the possible genetic origins of homosexuality are only one part of this development. By far the most important element is the testimony of countless homosexuals. The number who say their orientation is a choice make up only a tiny minority; and the candor of those who say it isn’t is overwhelming. To be sure, it is in the interests of gay people to affirm their lack of choice over the matter; but the consensus among homosexuals, the resilience of lesbian and gay minorities in the face of deep social disapproval and even a plague, suggests that homosexuality, whatever one would like to think, simply is not often chosen. A fundamental claim of natural law is that its truths are self-evident: Across continents and centuries, homosexuality is a self-evident fact of life.

How large this population is does not matter. One percent or ten percent: As long as a small but persistent part of the population is involuntarily gay, then the entire conservative politics of homosexuality rests on an unstable footing. It becomes simply a politics of denial or repression. Faced with a sizable and inextinguishable part of society, it can only pretend that it does not exist, or needn’t be addressed, or can somehow be dismissed. This politics is less coherent than even the politics that opposed civil rights for blacks thirty years ago, because at least that had some answer to the question of the role of blacks in society, however subordinate. Today’s conservatives have no role for homosexuals; they want them somehow to disappear, an option that was once illusory and is now impossible.

Some conservatives and conservative institutions have recognized this. They’ve even begun to use the term “homosexual,” implicitly accepting the existence of a constitutive characteristic. Some have avoided it by the innovative term “homosexualist,” but most cannot do so without a wry grin on their faces. The more serious opponents of equality for homosexuals finesse the problem by restricting their objections to “radical homosexuals,” but the distinction doesn’t help. They are still forced to confront the problem of unradical homosexuals, people whose sexuality is, presumably, constitutive. To make matters worse, the Roman Catholic Church—the firmest religious proponent of the conservative politics of homosexuality—has explicitly conceded the point. It declared in 1975 that homosexuality is indeed involuntary for many. In the recent Universal Catechism, the Church goes even further. Homosexuality is described as a “condition” of a “not negligible” number of people who “do not choose” their sexuality and deserve to be treated with “respect, compassion and sensitivity.” More critically, because of homosexuality’s involuntary nature, it cannot of itself be morally culpable (although homosexual acts still are). The doctrine is thus no longer “hate the sin but love the sinner;” it’s “hate the sin but accept the condition,” a position unique in Catholic theology, and one that has already begun to creak under the strain of its own tortuousness.

But the loss of intellectual solidity isn’t the only problem for the conservative politics of homosexuality. In a liberal polity, it has lost a good deal of its political coherence as well. When many people in a liberal society insist upon their validity as citizens and human beings, repression becomes a harder and harder task. It offends against fundamental notions of decency and civility to treat them as simple criminals or patients. To hunt them down, imprison them for private acts, subject government workers to surveillance and dismissal for reasons related to their deepest sense of personal identity becomes a policy not simply cruel but politically impossible in a civil order. For American society to return to the social norms around the question of homosexuality of a generation ago would require a renewed act of repression that not even many zealots could contemplate. What generations of inherited shame could not do, what AIDS could not accomplish, what the most decisive swing toward conservatism in the 1980s could not muster, must somehow be accomplished in the next few years. It simply cannot be done.

So even Patrick Buchanan is reduced to joke-telling; senators to professions of ignorance; military leaders to rationalizations of sheer discomfort. For those whose politics are a mere extension of religious faith, such impossibilism is part of the attraction (and spiritually, if not politically, defensible). But for conservatives who seek to act as citizens in a secular, civil order, the dilemma is terminal. An unremittingly hostile stance toward homosexuals runs the risk of sectarianism. At some point, not reached yet but fast approaching, their politics could become so estranged from the society in which it operates that it could cease to operate as a politics altogether.

II.

The second politics of homosexuality shares with the first a conviction that homosexuality as an inherent and natural condition does not exist. Homosexuality, in this politics, is a cultural construction, a binary social conceit (along with heterosexuality) forced upon the sexually amorphous (all of us). This politics attempts to resist this oppressive construct, subverting it and subverting the society that allows it to fester. Where the first politics takes as its starting point the Thomist faith in nature, the second springs from the Nietzschean desire to surpass all natural necessities, to attack the construct of “nature” itself. Thus the pursuit of a homosexual existence is but one strategy of many to enlarge the possibility for human liberation.

Call this the radical politics of homosexuality. For the radicals, like the conservatives, homosexuality is definitely a choice: the choice to be a “queer,” the choice to subvert oppressive institutions, the choice to be an activist. And it is a politics that, insofar as it finds its way from academic discourse into gay activism (and it does so fitfully), exercises a peculiar fascination for the adherents of the first politics. At times, indeed, both seem to exist in a bond of mutual contempt and admiration. That both prefer to use the word “queer,” the one in private, the other in irony, is only one of many resemblances. They both react with disdain to those studies that seem to reflect a genetic source for homosexuality; and they both favor, to some extent or other, the process of outing, because for both it is the flushing out of deviant behavior: for conservatives, of the morally impure, for radicals, of the politically incorrect. For conservatives, radical “queers” provide a frisson of cultural apocalypse and a steady stream of funding dollars. For radicals, the religious right can be tapped as an unreflective and easy justification for virtually any political impulse whatsoever.

Insofar as this radical politics is synonymous with a subcultural experience, it has stretched the limits of homosexual identity and expanded the cultural space in which some homosexuals can live. In the late 1980s the tactics of groups like Act-Up and Queer Nation did not merely shock and anger, but took the logic of shame-abandonment to a thrilling conclusion. To exist within their sudden energy was to be caught in a liberating rite of passage, which, when it did not transgress into political puritanism, exploded many of the cozy assumptions of closeted homosexual and liberal heterosexual alike.

This politics is as open-ended as the conservative politics is closed-minded. It seeks an end to all restrictions on homosexuality, but also the subversion of heterosexual norms, as taught in schools or the media. By virtue of its intellectual origins, it affirms a close connection with every other minority group, whose cultural subversion of white, heterosexual, male norms is just as vital. It sees its crusades—now for an AIDS czar, now against the Catholic Church’s abortion stance, now for the Rainbow Curriculum, now against the military ban—as a unified whole of protest, glorifying in its indiscriminateness as in its universality.

But like the conservative politics of homosexuality, which also provides a protective ghetto of liberation for its disciples, the radical politics of homosexuality now finds itself in an acute state of crisis. Its problem is twofold: Its conception of homosexuality is so amorphous and indistinguishable from other minority concerns that it is doomed to be ultimately unfocused; and its relationship with the views of most homosexuals—let alone heterosexuals—is so tenuous that at moments of truth (like the military ban) it strains to have a viable politics at all.

The trouble with gay radicalism, in short, is the problem with subversive politics as a whole. It tends to subvert itself. Act-Up, for example, an AIDS group that began in the late 1980s as an activist group dedicated to finding a cure and better treatment for people with AIDS, soon found itself awash in a cacophony of internal division. Its belief that sexuality was only one of many oppressive constructions meant that it was constantly tempted to broaden its reach, to solve a whole range of gender and ethnic grievances. Similarly, each organizing committee in each state of this weekend’s march on Washington was required to have a 50 percent “minority” composition. Even Utah. Although this universalist temptation was not always given in to, it exercised an enervating and dissipating effect on gay radicalism’s political punch.

More important, the notion of sexuality as cultural subversion distanced it from the vast majority of gay people who not only accept the natural origin of their sexual orientation, but wish to be integrated into society as it is. For most gay people—the closet cases and barflies, the construction workers and investment bankers, the computer programmers and parents—a “queer” identity is precisely what they want to avoid. In this way, the radical politics of homosexuality, like the conservative politics of homosexuality, is caught in a political trap. The more it purifies its own belief about sexuality, the less able it is to engage the broader world as a whole. The more it acts upon its convictions, the less able it is to engage in politics at all.

For the “queer” fundamentalists, like the religious fundamentalists, this is no problem. Politics for both groups is essentially an exercise in theater and rhetoric, in which dialogue with one’s opponent is an admission of defeat. It is no accident that Act-Up was founded by a playwright, since its politics was essentially theatrical: a fantastic display of rhetorical pique and visual brilliance. It became a national media hit, but eventually its lines became familiar and the audience’s attention wavered. New shows have taken its place and will continue to do so: But they will always be constrained by their essential nature, which is performance, not persuasion.

The limits of this strategy can be seen in the politics of the military ban. Logically, there is no reason for radicals to support the ending of the ban: It means acceptance of presumably one of the most repressive institutions in American society. And, to be sure, no radical arguments have been made to end the ban. But in the last few months, “queers” have been appearing on television proclaiming that gay people are just like anybody else and defending the right of gay Midwestern Republicans to serve their country. In the pinch, “queer” politics was forced to abandon its theoretical essence if it was to advance its purported aims: the advancement of gay equality. The military ban illustrated the dilemma perfectly. As soon as radicalism was required actually to engage America, its politics disintegrated. Similarly, “queer” radicalism’s doctrine of cultural subversion and separatism has the effect of alienating those very gay Americans most in need of support and help: the young and teenagers. Separatism is even less of an option for gays than for any other minority, since each generation is literally umbilically connected to the majority. The young are permanently in the hands of the other. By erecting a politics on a doctrine of separation and difference from the majority, “queer” politics ironically broke off dialogue with the heterosexual families whose cooperation is needed in every generation, if gay children are to be accorded a modicum of dignity and hope.

There’s an argument, of course, that radicalism’s politics is essentially instrumental; that by stretching the limits of what is acceptable it opens up space for more moderate types to negotiate; that, without Act-Up and Queer Nation, no progress would have been made at all. But this both insults the theoretical integrity of the radical position (they surely do not see themselves as mere adjuncts to liberals) and underestimates the scope of the gay revolution that has been quietly taking place in America. Far more subversive than media-grabbing demonstrations on the evening news has been the slow effect of individual, private Americans becoming more open about their sexuality. The emergence of role models, the development of professional organizations and student groups, the growing influence of openly gay people in the media and the extraordinary impact of AIDS on families and friends have dwarfed radicalism’s impact on the national consciousness. Likewise, the greatest public debate about homosexuality yet—the military debate—took place not because radicals besieged the Pentagon, but because of the ordinary and once-anonymous Americans within the military who simply refused to acquiesce in their own humiliation any longer. Their courage was illustrated not in taking to the streets in rage but in facing their families and colleagues with integrity.

And this presents the deepest problem for radicalism. As the closet slowly collapses, as gay people enter the mainstream, as suburban homosexuals and Republican homosexuals emerge blinking into the daylight, as the gay ghettos of the inner cities are diluted by the gay enclaves of the suburbs, the whole notion of a separate and homogeneous “queer” identity will become harder to defend. Far from redefining gay identity, “queer” radicalism may actually have to define itself in opposition to it. This is implicit in the punitive practice of “outing” and in the increasingly anti-gay politics of some “queer” radicals. But if “queer” politics is to survive, it will either have to be proved right about America’s inherent hostility to gay people or become more insistent in its separatism. It will have to intensify its hatred of straights or its contempt for gays. Either path is likely to be as culturally creative as it is politically sterile.

III.

Between these two cultural poles, an appealing alternative presents itself. You can hear it in the tone if not the substance of civilized columnists and embarrassed legislators, who are united most strongly by the desire that this awkward subject simply go away. It is the moderate politics of homosexuality. Unlike the conservatives and radicals, the moderates do believe that a small number of people are inherently homosexual, but they also believe that another group is susceptible to persuasion in that direction and should be dissuaded. These people do not want persecution of homosexuals, but they do not want overt approval either. They are most antsy when it comes to questions of the education of children but feel acute discomfort in supporting the likes of Patrick Buchanan and Pat Robertson.

Thus their politics has all the nuance and all the disingenuousness of classically conservative politics. They are not intolerant, but they oppose the presence of openly gay teachers in school; they have gay friends but hope their child isn’t homosexual; they are in favor of ending the military ban but would seek to do so either by reimposing the closet (ending discrimination in return for gay people never mentioning their sexuality) or by finding some other kind of solution, such as simply ending the witch hunts. If they support sodomy laws (pour decourager les autres), they prefer to see them unenforced. In either case, they do not regard the matter as very important. They are ambivalent about domestic partnership legislation but are offended by gay marriage. Above all, they prefer that the subject of homosexuality be discussed with delicacy and restraint, and are only likely to complain to their gay friends if they insist upon “bringing the subject up” too often.

This position too has a certain coherence. It insists that politics is a matter of custom as well as principle and that, in the words of Nunn, caution on the matter of sexuality is not so much a matter of prejudice as of prudence. It places a premium on discouraging the sexually ambivalent from resolving their ambiguity freely in the direction of homosexuality, because, society being as it is, such a life is more onerous than a heterosexual one. It sometimes exchanges this argument for the more honest one: that it wishes to promote procreation and the healthy rearing of the next generation and so wishes to create a cultural climate that promotes heterosexuality.

But this politics too has become somewhat unstable, if not as unstable as the first two. And this instability stems from an internal problem and a related external one. Being privately tolerant and publicly disapproving exacts something of a psychological cost on those who maintain it. In theory, it is not the same as hypocrisy; in practice, it comes perilously close. As the question of homosexuality refuses to disappear from public debate, explicit positions have to be taken. What once could be shrouded in discretion now has to be argued in public. For those who privately do not believe that homosexuality is inherently evil or always chosen, it has become increasingly difficult to pretend otherwise in public. Silence is an option—and numberless politicians are now availing themselves of it—but increasingly a decision will have to be made. Are you in favor of or against allowing openly gay women and men to continue serving their country? Do you favor or oppose gay marriage? Do you support the idea of gay civil rights laws? Once these questions are asked, the gentle ambiguity of the moderates must be flushed out; they have to be forced either into the conservative camp or into formulating a new politics that does not depend on a code of discourse that is fast becoming defunct.

They cannot even rely upon their gay friends anymore. What ultimately sustained this politics was the complicity of the gay elites in it: their willingness to stay silent when a gay joke was made in their presence, their deference to the euphemisms—roommate, friend, companion—that denoted their lovers, husbands and wives, their support of the heterosexual assumptions of polite society. Now that complicity, if not vanished, has come under strain. There are fewer and fewer J. Edgar Hoovers and Roy Cohns, and the thousands of discreet gay executives and journalists, businessmen and politicians who long deferred to their sexual betters in matters of etiquette. AIDS rendered their balancing act finally absurd. Many people—gay and straight—were forced to have the public courage of their private convictions. They had to confront the fact that their delicacy was a way of disguising shame; that their silence was a means of hiding from themselves their intolerance. This is not an easy process; indeed, it can be a terrifying one for both gay and straight people alike. But there comes a point after which omissions become commissions; and that point, if not here yet, is coming. When it arrives, the moderate politics of homosexuality will be essentially over.

IV.

The politics that is the most durable in our current attempt to deal with the homosexual question is the contemporary liberal politics of homosexuality. Like the moderates, the liberals accept that homosexuality exists, that it is involuntary for a proportion of society, that for a few more it is an option and that it need not be discouraged. Viewing the issue primarily through the prism of the civil rights movement, the liberals seek to extend to homosexuals the same protections they have granted to other minorities. The prime instrument for this is the regulation of private activities by heterosexuals, primarily in employment and housing, to guarantee non-discrimination against homosexuals.

Sometimes this strategy is echoed in the rhetoric of Edward Kennedy, who, in the hearings on the military gay ban, linked the gay rights agenda with the work of such disparate characters as John Kennedy, Cesar Chavez and Martin Luther King Jr. In other places, it is reflected in the fact that sexual orientation is simply added to the end of a list of minority conditions, in formulaic civil rights legislation. And this strategy makes a certain sense. Homosexuals are clearly subject to private discrimination in the same way as many other minorities; and linking the causes helps defuse some of the trauma that the subject of homosexuality raises. Liberalism properly restricts itself to law—not culture—in addressing social problems; and by describing all homosexuals as a monolithic minority, it is able to avoid the complexities of the gay world as a whole, just as blanket civil rights legislation draws a veil over the varieties of black America by casting the question entirely in terms of non-black attitudes.

But this strategy is based on two assumptions: that sexuality is equivalent to race in terms of discrimination, and that the full equality of homosexuals can be accomplished by designating gay people as victims. Both are extremely dubious. And the consequence of these errors is to mistarget the good that liberals are trying to do.

Consider the first. Two truths (at least) profoundly alter the way the process of discrimination takes place against homosexuals and against racial minorities and distinguish the history of racial discrimination in this country from the history of homophobia. Race is always visible; sexuality can be hidden. Race is in no way behavioral; sexuality, though distinct from sexual activity, is profoundly linked to a settled pattern of behavior.

For lesbians and gay men, the option of self-concealment has always existed and still exists, an option that means that in a profound way, discrimination against them is linked to their own involvement, even acquiescence. Unlike blacks three decades ago, gay men and lesbians suffer no discernible communal economic deprivation and already operate at the highest levels of society: in boardrooms, governments, the media, the military, the law and industry. They may have advanced so far because they have not disclosed their sexuality, but their sexuality as such has not been an immediate cause for their disadvantage. In many cases, their sexuality is known, but it is disclosed at such a carefully calibrated level that it never actually works against them. At lower levels of society, the same pattern continues. As in the military, gay people are not uniformly discriminated against; openly gay people are.

Moreover, unlike blacks or other racial minorities, gay people are not subject to inherited patterns of discrimination. When generation after generation is discriminated against, a cumulative effect of deprivation may take place, where the gradual immiseration of a particular ethnic group may intensify with the years. A child born into a family subject to decades of accumulated poverty is clearly affected by a past history of discrimination in terms of his or her race. But homosexuality occurs randomly anew with every generation. No sociological pattern can be deduced from it. Each generation gets a completely fresh start in terms of the socioeconomic conditions inherited from the family unit.

This is not to say that the psychological toll of homosexuality is less problematic than that of race, but that it is different: in some ways better; in others, worse. Because the stigma is geared toward behavior, the level of shame and collapse of self-esteem may be more intractable. To reach puberty and find oneself falling in love with members of one’s own sex is to experience a mixture of self-discovery and self-disgust that never leaves a human consciousness. If the stigma is attached not simply to an obviously random characteristic, such as skin pigmentation, but to the deepest desires of the human heart, then it can eat away at a person’s sense of his own dignity with peculiar ferocity. When a young person confronts her sexuality, she is also completely alone. A young heterosexual black or Latino girl invariably has an existing network of people like her to interpret, support and explain the emotions she feels when confronting racial prejudice for the first time. But a gay child generally has no one. The very people she would most naturally turn to—the family—may be the very people she is most ashamed in front of.

The stigma attached to sexuality is also different than that attached to race because it attacks the very heart of what makes a human being human: her ability to love and be loved. Even the most vicious persecution of racial minorities allowed, in many cases, for the integrity of the marital bond or the emotional core of a human being. When it did not, when Nazism split husbands from wives, children from parents, when apartheid or slavery broke up familial bonds, it was clear that a particularly noxious form of repression was taking place. But the stigma attached to homosexuality begins with such a repression. It forbids, at a child’s earliest stage of development, the possibility of the highest form of human happiness. It starts with emotional terror and ends with mild social disapproval. It’s no accident that, later in life, when many gay people learn to reconnect the bonds of love and sex, they seek to do so in private, even protected from the knowledge of their family.

This unique combination of superficial privilege, acquiescence in repression and psychological pain is a human mix no politics can easily tackle. But it is the mix liberalism must address if it is to reach its goal of using politics to ease human suffering. The internal inconsistency of this politics is that by relying on the regulation of private activity, it misses this its essential target—and may even make matters worse. In theory, a human rights statute sounds like an ideal solution, a way for straights to express their concern and homosexuals to legitimate their identity. But in practice, it misses the point. It might grant workers a greater sense of security were they to come out in the office; and it might, by the publicity it generates, allow for greater tolerance and approval of homosexuality generally. But the real terror of coming out is deeper than economic security, and is not resolved by it; it is related to emotional and interpersonal dignity. However effective or comprehensive anti-discrimination laws are, they cannot reach far enough to tackle this issue; it is one that can only be addressed person by person, life by life, heart by heart.

For these reasons, such legislation rarely touches the people most in need of it: those who live in communities where disapproval of homosexuality is so intense that the real obstacles to advancement remain impervious to legal remedy. And even in major urban areas, it can be largely irrelevant. (On average some one to two percent of anti-discrimination cases have to do with sexual orientation; in Wisconsin, which has had such a law in force for more than a decade and is the largest case study, the figure is 1.1 percent.) As with other civil rights legislation, those least in need of it may take fullest advantage: the most litigious and articulate homosexuals, who would likely brave the harsh winds of homophobia in any case.

Anti-discrimination laws scratch the privileged surface, while avoiding the problematic depths. Like too many drugs for AIDS, they treat the symptoms of the homosexual problem without being anything like a cure; they may buy some time, and it is a cruel doctor who, in the face of human need, would refuse them. But they have about as much chance of tackling the deep roots of the gay-straight relationship as azt has of curing AIDS. They want to substitute for the traumatic and difficult act of coming out the more formal and procedural act of legislation. But law cannot do the work of life. Even culture cannot do the work of life. Only life can do the work of life.

As the experience in Colorado and elsewhere shows, this strategy of using law to change private behavior also gives a fatal opening to the conservative politics of homosexuality. Civil rights laws essentially dictate the behavior of heterosexuals, in curtailing their ability to discriminate. They can, with justification, be portrayed as being an infringement of individual liberties. If the purpose of the liberal politics is to ensure the equality of homosexuals and their integration into society, it has thus achieved something quite peculiar. It has provided fuel for those who want to argue that homosexuals are actually seeking the infringement of heterosexuals’ rights and the imposition of their values onto others. Much of this is propaganda, of course, and is fueled by fear and bigotry. But it works because it contains a germ of truth. Before most homosexuals have even come out of the closet, they are demanding concessions from the majority, including a clear curtailment of economic and social liberties, in order to ensure protections few of them will even avail themselves of. It is no wonder there is opposition, or that it seems to be growing. Nine states now have propositions to respond to what they see as the “special rights” onslaught.

In the process, the liberal politics of homosexuality has also reframed the position of gays in relation to straights. It has defined them in a permanent supplicant status, seeing gay freedom as dependent on straight enlightenment, achievable only by changing the behavior of heterosexuals. The valuable political insight of radicalism is that this is a fatal step. It could enshrine forever the notion that gay people are a vulnerable group in need of protection. By legislating homosexuals as victims, it sets up a psychological dynamic of supplication that too often only perpetuates cycles of inadequacy and self-doubt. Like blacks before them, gay people may grasp at what seems to be an escape from the prison of self-hatred, only to find it is another prison of patronized victimology. By seeking salvation in the hands of others, they may actually entrench in law and in their minds the notion that their equality is dependent on the goodwill of their betters. It isn’t. This may have made a good deal of sense in the case of American blacks, with a clear and overwhelming history of accumulated discrimination and a social ghetto that seemed impossible to breach. But for gay people—already prosperous, independent and on the brink of real integration—that lesson should surely now be learned. To place our self-esteem in the benevolent hands of contemporary liberalism is more than a mistake. It is a historic error.

V.

If there were no alternative to today’s liberal politics of homosexuality, it should perhaps be embraced by default. But there is an alternative politics that is imaginable, which once too was called liberal. It begins with the view that for a small minority of people, homosexuality is an involuntary condition that can neither be denied nor permanently repressed. It adheres to an understanding that there is a limit to what politics can achieve in such an area, and trains its focus not on the behavior of private heterosexual citizens but on the actions of the public and allegedly neutral state. While it eschews the use of law to legislate culture, it strongly believes that law can affect culture indirectly. Its goal would be full civil equality for those who, through no fault of their own, happen to be homosexual; and would not deny homosexuals, as the other four politics do, their existence, integrity, dignity or distinctness. It would attempt neither to patronize nor to exclude.

This liberal politics affirms a simple and limited criterion: that all public (as opposed to private) discrimination against homosexuals be ended and that every right and responsibility that heterosexuals enjoy by virtue of the state be extended to those who grow up different. And that is all. No cures or re-educations; no wrenching civil litigation; no political imposition of tolerance; merely a political attempt to enshrine formal civil equality, in the hope that eventually, the private sphere will reflect this public civility. For these reasons, it is the only politics that actually tackles the core political problem of homosexuality and perhaps the only one that fully respects liberalism’s public-private distinction. For these reasons, it has also the least chance of being adopted by gays and straights alike.

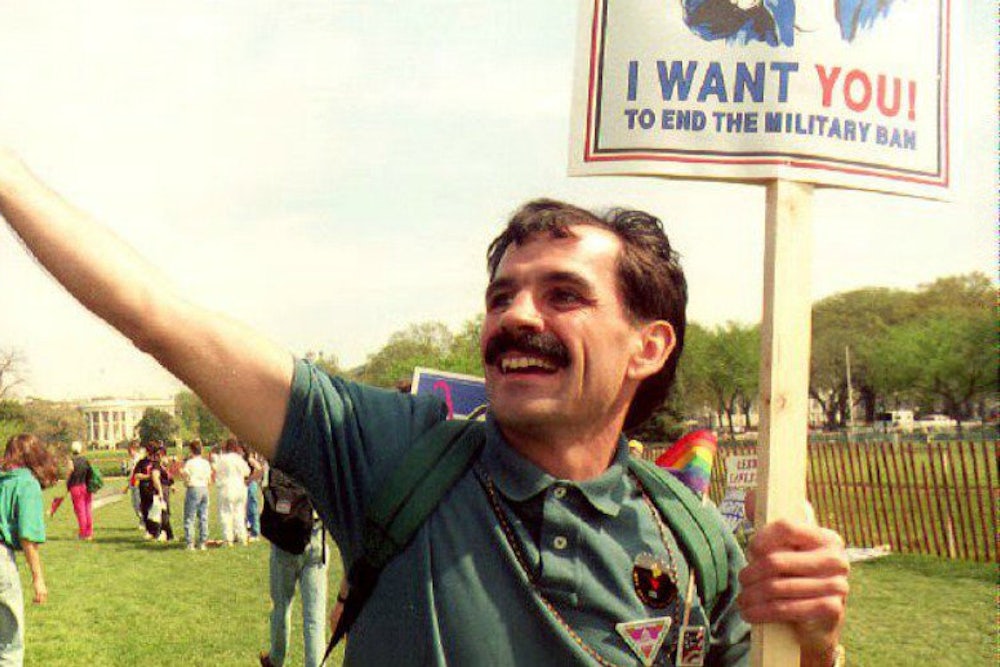

But is it impossible? By sheer circumstance, this politics has just been given its biggest boost since the beginning of the debate over the homosexual question. The military ban is by far the most egregious example of proactive government discrimination in this country. By conceding, as the military has done, the excellent service that many gay and lesbian soldiers have given to their country, the military has helped shatter a thousand stereotypes about their nature and competence. By focusing on the mere admission of homosexuality, the ban has purified the debate into a matter of the public enforcement of homophobia. Unlike anti-discrimination law, the campaign against the ban does not ask any private citizens to hire or fire anyone of whom they do not approve; it merely asks public servants to behave the same way with avowed homosexuals as with closeted ones.

Because of its timing, because of the way in which it has intersected with the coming of age of gay politics, the military debate has a chance of transforming the issue for good. Its real political power—and the real source of the resistance to it—comes from its symbolism. The acceptance of gay people at the heart of the state, at the core of the notion of patriotism, is anathema to those who wish to consign homosexuals to the margins of society. It offends conservatives by the simplicity of its demands, and radicals by the traditionalism of the gay people involved; it dismays moderates, who are forced publicly to discuss this issue for the first time; and it disorients liberals, who find it hard to fit the cause simply into the rubric of minority politics. For instead of seeking access, as other minorities have done, gays in the military are simply demanding recognition. They start not from the premise of suppliance, but of success, of proven ability and prowess in battle, of exemplary conduct and ability. This is a new kind of minority politics. It is less a matter of complaint than of pride; less about subversion than about the desire to contribute equally.

The military ban also forces our society to deal with the real issues at stake in dealing with homosexuals. The country has been forced to discuss sleeping arrangements, fears of sexual intimidation, the fraught emotional relations between gays and straights, the violent reaction to homosexuality among many young males, the hypocrisy involved in much condemnation of gays and the possible psychological and emotional syndromes that make homosexuals allegedly unfit for service. Like a family engaged in the first, angry steps toward dealing with a gay member, the country has been forced to debate a subject honestly—even calmly—in a way it never has before. This is a clear and enormous gain. Whatever the result of this process, it cannot be undone.

But the critical measure necessary for full gay equality is something deeper and more emotional perhaps than even the military. It is equal access to marriage. As with the military, this is a question of formal public discrimination. If the military ban deals with the heart of what it is to be a citizen, the marriage ban deals with the core of what it is to be a member of civil society. Marriage is not simply a private contract; it is a social and public recognition of a private commitment. As such it is the highest public recognition of our personal integrity. Denying it to gay people is the most public affront possible to their civil equality.

This issue may be the hardest for many heterosexuals to accept. Even those tolerant of homosexuals may find this institution so wedded to the notion of heterosexual commitment that to extend it would be to undo its very essence. And there may be religious reasons for resisting this that require far greater discussion than I can give them here. But civilly and emotionally, the case is compelling. The heterosexuality of marriage is civilly intrinsic only if it is understood to be inherently procreative; and that definition has long been abandoned in civil society. In contemporary America, marriage has become a way in which the state recognizes an emotional and economic commitment of two people to each other for life. No law requires children to consummate it. And within that definition, there is no civil way it can logically be denied homosexuals, except as a pure gesture of public disapproval. (I leave aside here the thorny issue of adoption rights, which I support in full. They are not the same as the right to marriage and can be legislated, or not, separately.)

In the same way, emotionally, marriage is characterized by a kind of commitment that is rare even among heterosexuals. Extending it to homosexuals need not dilute the special nature of that commitment, unless it is understood that gay people, by their very nature, are incapable of it. History and experience suggest the opposite. It is not necessary to prove that gay people are more or less able to form long-term relationships than straights for it to be clear that, at least, some are. Giving these people a right to affirm their commitment doesn’t reduce the incentive for heterosexuals to do the same, and even provides a social incentive for lesbians and gay men to adopt socially beneficial relationships.

But for gay people, it would mean far more than simple civil equality. The vast majority of us—gay and straight—are brought up to understand that the apex of emotional life is found in the marital bond. It may not be something we achieve, or even ultimately desire, but its very existence premises the core of our emotional development. It is the architectonic institution that frames our emotional life. The marriages of others are a moment for celebration and self-affirmation; they are the way in which our families and friends reinforce us as human beings. Our parents consider our emotional lives to be more important than our professional ones, because they care about us at our core, not at our periphery. And it is not hard to see why the marriage of an offspring is often regarded as the high point of any parent’s life.

Gay people always know this essential affirmation will be denied them. Thus their relationships are given no anchor, no endpoint, no way of integrating them fully into the network of family and friends that makes someone a full member of civil society. Even when those relationships become essentially the same—or even stronger—than straight relationships, they are never accorded the dignity of actual equality. Husbands remain “friends”; wives remain “partners.” The very language sends a powerful signal of fault, a silent assumption of internal disorder or insufficiency. The euphemisms—and the brave attempt to pretend that gay people don’t need marriage—do not successfully conceal the true emotional cost and psychological damage that this signal exacts. No true progress in the potential happiness of gay teenagers or in the stability of gay adults or in the full integration of gay and straight life is possible, or even imaginable, without it.

These two measures—simple, direct, requiring no change in heterosexual behavior and no sacrifice from heterosexuals—represent a politics that tackles the heart of homophobia while leaving homophobes their freedom. It allows homosexuals to define their own future and their own identity and does not place it in the hands of the other. It makes a clear, public statement of equality, while leaving all the inequalities of emotion and passion to the private sphere, where they belong. It does not legislate private tolerance, it declares public equality. It banishes the paradigm of victimology and replaces it with one of integrity. It requires one further step, of course, which is to say the continuing effort for honesty on the part of homosexuals themselves. This is not easily summed up in the crude phrase “coming out”; but it finds expression in the myriad ways in which gay men and lesbians talk, engage, explain, confront and seek out the other. Politics cannot substitute for this; heterosexuals cannot provide it. And, while it is not in some sense fair that homosexuals have to initiate the dialogue, it is a fact of life. Silence, if it does not equal death, equals the living equivalent.

It is not the least of the ironies of this politics that its objectives are in some sense not political at all. The family is prior to the liberal state; the military is coincident with it. Heterosexuals would not conceive of such rights as things to be won, but as things that predate modern political discussion. But it says something about the unique status of homosexuals in our society that we now have to be political in order to be prepolitical. Our battle is not for political victory but for personal integrity. Just as many of us had to leave our families in order to join them again, so now as citizens, we have to embrace politics, if only ultimately to be free of it. Our lives may have begun in simplicity, but they have not ended there. Our dream, perhaps, is that they might.