Slovakian photographer Yuri Dojc, 69, insists that he doesn’t believe in miracles, and doesn’t consider himself a particularly religious man. Nonetheless, he describes his Last Folio project as the result of a series of “miracles” that began with his father’s funeral, where he met Mrs. Vajnorska, an Auschwitz survivor who became Dojc’s “second mother.” She showed him around Slovakia and introduced him to other survivors, whom he photographed. That, in turn, led to his discovery in 2006 of an abandoned Jewish schoolhouse, synagogue, and ritual bath in eastern Slovakia that had remained largely undisturbed since the day in 1942 when everyone was deported to concentration camps.

“So what inspired me?” he asks, repeating my question. “Life. Circumstances and coincidences.”

Last Folio has toured the world as an art installation, been the subject of a documentary short produced by Katya Krausova, and twelve of its photos have been selected for the permanent collection of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Now, this June, Random House’s Prestel division has published Last Folio: A Photographic Memory: a book of Dojc’s photos of books.

I interviewed Dojc recently about his nearly decade-old project. Here’s how he described it:

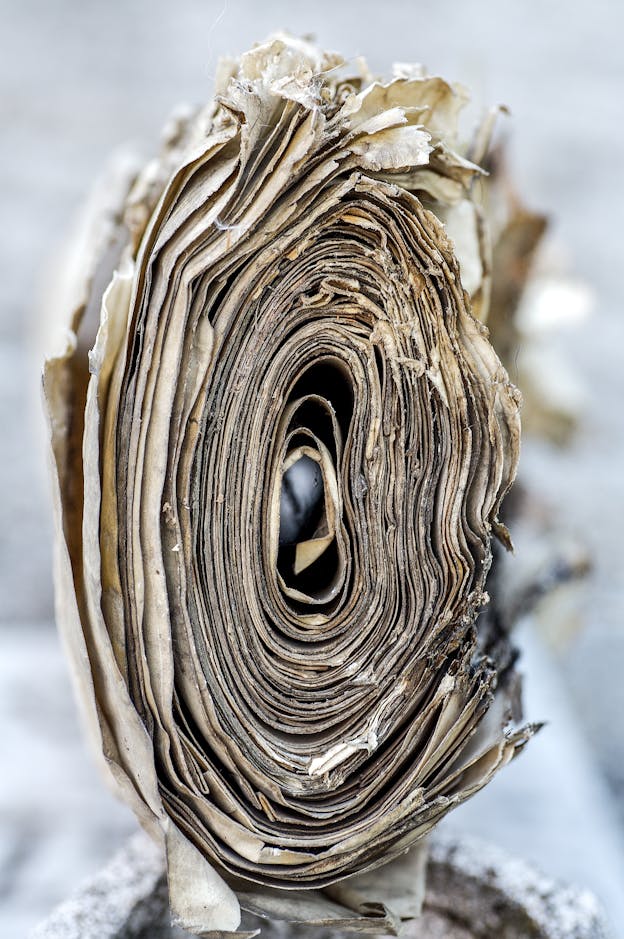

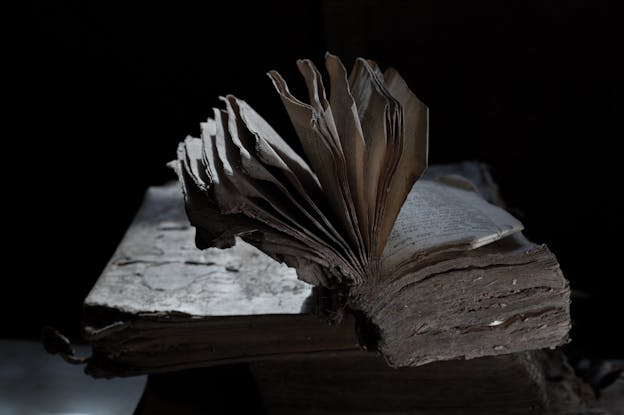

Yuri Dojc: Most photographers who do art projects usually, they figure out what is hot now, what is in, or what is what they’d like to do, what they can get the most mileage from. They plan the map and they go for it. None of that happened here. Once we entered that school we could not leave. I was hypnotized. Hypnotized by the sheer beauty of the books. Some people say they look horrible. To me they were absolutely stunning. Many people lately—I know this because I’m very involved in the art world—are fascinated by abandoned buildings. People go to destroyed and abandoned buildings, People go to Chernobyl and photograph abandoned buildings. But people know what they’re getting into. We did not plan to find an abandoned building.

We are actually uncovering cultural memory here. There are levels and levels of life which were destroyed during World War II, and destruction is still going on. And then to have the privilege of coming upon this situation, decades after the war. Trying to visually, I wouldn’t say preserve it—visually sort of mark it so there’s some kind of memory of this time. For me it wasn’t an abandoned building, it was part of a heritage, it was part of my heritage that I didn’t know anything about. I left Czechoslovakia when I was a young man who was not questioning or wrestling with that kind of thought. You’re a young guy, you’re a teenager, your interests are, you know, girls and motorcycles. You don’t think about memory, about culture, about what was lost. But you’re 50 and you think about those things totally differently.

We found out that many of the books had a stamp which tells you that each book belongs to somebody, and 99 percent, 99.9 percent of those people died in concentration camps. People didn’t most likely have a grave. So this book is the last proof of [their] existence. Another miracle happened when we came to another town, we found 5,000 books or something just lying there. Picking it up book by book and opening a book wherever there was a stamp. And the stamp will tell you: “name, profession, city where the owner was from.” Mostly craftspeople, there would be bookbinder, tailor, cook, plumber. Basic, basic professions.

[Katya] comes to me and says, “You never told me about your family. Your grandfather, what was his name?” I said, “Why do you want to know this?” She said “I’m just curious.” I said “Jacob.” “So what was his profession?” I said “He was a tailor.” She said “What kind of tailor?” I said “Why are you asking me this?” “Tell me.” “He did women’s clothing.” “And which town was he from?” And then she gives me a little book and says “Look what I found.” My grandfather, I never met him. All I remember is one photo my father gave to me that is my grandfather during the war. He has a Star of David. That was all I had of him, physically. Now I am standing in a room full of books holding the only thing my grandfather touched in his life, this book. Is there miracles or not?

They’re all distressed old books, but in each picture I tried to do something unique. I like to give a personality to each book. So if there’s no name of the owner at least the viewer will realize that his book belonged to somebody. I treated them as people. I treated them as gentle as I could.

I think in the world and in Europe especially, I am photographing something that happened 70 years ago. I am petrified. Things like that cannot happen again. I know we hear all these slogans, “Never again,” and I am feeling skeptical. I am trying to preserve something that was destroyed and I ask myself: Is the same thing happening again and the world is putting their heads in the sand? I would like to add something to the present time. Because people have very short memories. There are horrible things happening every day. If I don’t show the past then how will people understand the present? This book is not going to be a best seller by any stretch of the imagination. But if a few people can learn something from it, well. I am an artist, we only can do so much in our life. Many people ask me, “Did you try to preserve the books?” I am not really a preserver of the books; I am a chronicler of what’s passed.

When we went to the Library of Congress, the chief librarian asked if the books were valuable, were they just ordinary praying books. He’s a very imposing guy, Dr. [James] Billington, and Katya’s very tiny and she looks up at him and says, “You preside over the largest library in the world and you have the first edition of all the great books. But in a little town in Slovakia these books were the only books these people possessed. So were they valuable? They were properly valuable to the people who owned them. But do they have monetary value? Probably not.” And he was like, “Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry, you’re absolutely right.” It was a very touching moment, because it’s not about books, really. Of course I cannot preserve them. First of all, they are beyond preservation. They are full of bugs; many times I had to wear gloves and a mask. But every time I put a mask and gloves it lasted about two minutes. I just cannot do that. I need to be physically close to them. The book of my grandfather I have here, with me.

By the way, the project is still on. I cannot stop it, honestly. It’s kind of inescapable.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.