My guilty pleasure is reading other people’s email. Since I study cybersecurity, friends sometimes ask me whether I can hack into their email accounts, but I actually have neither the skill nor the will. Instead, I can get my fix from publicly released email archives. Give me a few thousand mundane emails from Hillary Clinton’s Blackberry or the gubernatorial offices of Chris Christie or Jeb Bush and I’ll happily neglect my own inbox for hours to pore over them. I’m hardly a political junkie. But when thousands of pages of Hillary Clinton’s correspondence were released last Tuesday night, I found myself compulsively perusing the email archives.

Partisans and reporters, of course, may go through these emails in a completely different spirit, looking for evidence of wrongdoing and corruption. In that regard, the latest Clinton release has been disappointing, revealing no consequential political machinations or dark and complex secrets. Most of the emails released last week by the Department of State are profoundly boring—records of people scheduling flights, or making to-do lists, or reading news stories about themselves. None of them, or at least none of the ones I’ve seen, suggest any scandalous government conspiracies or cover-ups. (Of course, many of them have also had considerable portions redacted prior to release.)

But while Hillary Clinton’s emails don’t hint at any Shonda Rhimes-worthy melodrama in the State Department, they do offer tiny glimpses of Clinton and her correspondents at perhaps their most unguarded and unintentionally humorous. Those little windows into the mundane everyday dramas of Clinton and her staff, mixed in with discussions of serious world affairs and official State Department business, are what make email archives so compelling—they’re so clearly not press releases or official statements, or polished public posturing of any kind.

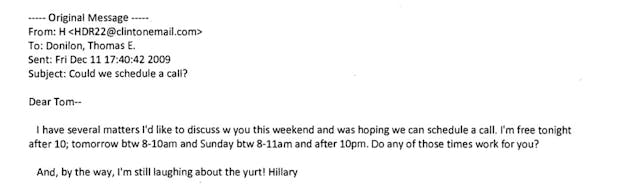

There are intriguing references to inside jokes and in-person conversations that we can only guess at, as in a December 11, 2009 email from Clinton to then-deputy National Security Advisor Thomas Donilon which ends: “And, by the way, I’m still laughing about the yurt!”

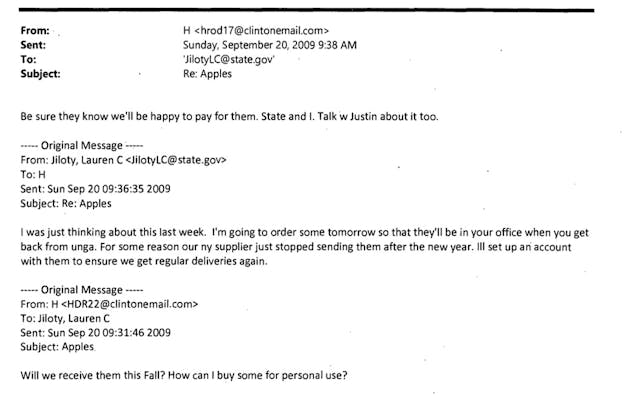

There are bizarrely specific, seasonal queries, such as the Sept. 20, 2009 email with the subject line “Apples,” in which Clinton writes to her special assistant Lauren Jiloty: “Will we receive them this Fall? How can I buy some for personal use?”

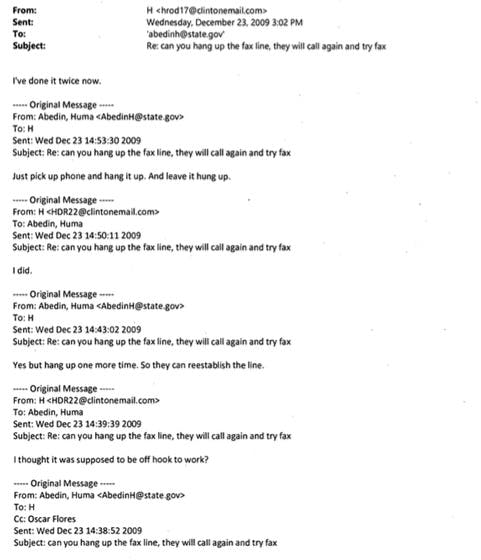

And then there is the ongoing saga of malfunctioning fax machines. “My fax is broken! So Huma is coming to print for me,” Clinton wrote on July 14, 2009 to her senior advisor and Chief of Speechwriting Lissa Muscatine. On August 24, 2009, Clinton wrote to her senior advisor Philippe Reines, “My fax is broken, so I didn’t get any clips. I hope to get it fixed today and hope to receive all that I missed.” Then, on Dec. 23, 2009, there’s a hilarious exchange between Clinton and Abedin as they attempt to troubleshoot the broken fax machine: “Can you hang up the fax line, they will call again and try fax” Abedin wrote. Clinton responded: “I thought it was supposed to be off hook to work?” Abedin: “Yes but hang up one more time. So they can reestablish the line.” Clinton: “I did.” Abedin: “Just pick up phone and hang it up. And leave it hung up.” Clinton: “I’ve done it twice now.”

The “powerful politicians—they’re just like us!” sensation is part of the appeal of these emails: we get to watch as they wrestle with their fax machines, reschedule conference calls, and struggle with smartphone punctuation. (In a particularly period-happy exchange with Clinton on April 12, 2009, Senator Barbara Mikulski wrote “I will be @ your. Foreign. Ops. Hearing.” and “Loved picture of you+obama on. The. Lawn. Time for. Spring and the resurrection.”)

For all the fuss about whether or not Clinton is “relatable” as a candidate, her emails—so obviously unstudied and unintended for the public eye—render her daily routines strikingly familiar and mundane. There are no major gaffes or dramatic reveals in these messages. The now-infamous “Time for some traffic problems in Fort Lee” email from former Christie deputy chief of staff Bridget Anne Kelly at least pertained to a real incident of misuse of political power. Clinton’s inquiries into what kind of rugs she saw in China are merely diverting.

Reading the correspondence and private writings of famous people is not new. We read the collected letters of Thomas Jefferson and C.S. Lewis and Edith Wharton, the private diaries of John Quincy Adams, Harry Truman, and Virginia Woolf. And politicians’ email archives are, in some ways, not unlike these tomes, at least insofar as the messages offer readers a similarly intimate glimpse of their authors’ daily lives, their petty concerns and recurring anxieties, friendships and jokes, fears and frustrations—who they are and how they act when they think no one is watching. Thomas Jefferson, too, was concerned with fruit, writing to James Madison from Fontainebleau on Oct. 28, 1785, “They have no apples here to compare with our Redtown pippin. They have nothing which deserves the name of a peach; there being not sun enough to ripen the plum-peach and the best of their soft peaches being like our autumn peaches.”

In other ways, of course, the letters of Thomas Jefferson and the email missives of Chris Christie’s aides could not be more dissimilar—and not only because our epistolary skills have deteriorated across the centuries. Our emails are more hurried and less carefully crafted, written during our crankier and less considered moments, rather than our most introspective and thoughtful ones. Email archives to some extent have less in common with collections of intimate correspondence than they do with the jumbled, disjoint scribblings of Mark Twain’s pocket notebooks.

Reading these messages is a rare way to understand the texture of someone else’s daily life, the rhythm and tone of their most trivial and off-hand interactions, the eccentricities and frustrations of their most honest and unguarded moments. There's something shameful but compelling about mildly invading a politician or celebrity’s privacy, about reading words that were never meant for public eyes. Miranda July’s 2013 project “We Think Alone,” featuring emails on particular topics by a variety of well-known authors, tapped into a similar desire to peep into the private online worlds of famous people. “I have always loved reading other people’s emails,” July told the Huffington Post, adding, “There is something about the mundane-ness that feels very intimate to me.”

In one of the emails included in July’s project, Lena Dunham writes to her boyfriend Jack Antonoff: “Is it unattractive to send you a link to a life changing nasal oil? I got it on Friday and every day since has been perfect.” Such revelations intrigue us not because they are salacious or scandalous but precisely because they aren’t.

Above all, perhaps, reading other people’s email is a welcome escape from our own inboxes. Even though most of Hillary Clinton’s released emails are just concerned with the tiny details of daily life and work—just like most of the emails we all receive and send every day—they provide a welcome means of procrastination. Instead of dealing with your own life, in all its dreary details, you look over someone’s shoulder—and it’s fascinating.

The banality of email archives is a reminder of how much of our lives and daily communication is occupied by the logistics of scheduling meetings, coordinating phone calls, making travel arrangements, and trying to fix the fax machine. If, in the future, historians study our email archives, they will likely conclude that our days were spent constantly communicating but saying very little of substance—something many of us already suspect from our own work lives.

“Every age has a keyhole to which its eye is pasted,” Mary McCarthy wrote in “My Confession,” a 1953 essay about 1930s New York. For the Internet age, email is a crucial keyhole—a way to peer into the inner workings of government offices and powerful politicians, as well as movie stars and studio executives. Much of what we learn is boring, but the boring stuff is bizarrely compelling: Why does Hillary Clinton need help buying apples? What yurt is she laughing about with Thomas Donilon? And what on earth is wrong with that fax machine?