Publishing houses, no less than people, have personalities. To be sure, certain large corporate presses have identities that are primarily mercenary, with catalogues consisting almost entirely of a mishmash of aspiring bestsellers. But among the smaller, individually run literary presses, the ones that nurture the books most likely to last, logos are marks of character. To see the emblem of a quality publisher on the spine of a book is to have a measure of its ambition and merit. From New Directions we expect strenuous modernist experimentation, from Farrar, Strauss and Giroux substance and style, from McSweeney’s mischievous playfulness not just in the words but also in the book design.

Over the last quarter century, Drawn & Quarterly (D+Q) has achieved a rare feat among comic book publishers, carving out for itself a status as distinctive as such legendary literary presses as New Directions. Individual D+Q titles have often been distinguished and collectively they add up to a transformation in the possibility of comics. The D+Q backlist is rich in volumes that have been at the forefront of making comics an accepted literary and visual form—works by such prominent cartoonists as Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware, Chester Brown, Seth, Julie Doucet, Adrian Tomine, Yoshihiro Tatsumi. While each D+Q book displays a singular temperament, taken together they form a common sensibility or gestalt. To the often shoddy and schlocky world of comics, D+Q brought elegance, sophistication, cosmopolitanism, a literary commitment to delicately told stories combined with alertness to tactile sensuousness and eye-pleasing design rooted in a fine arts sensibility.

If D+Q has been the New Directions of cartooning, then Chris Oliveros, who founded the company, has played the same taste-shaping role as legendary New Directions founder James Laughlin. Just as Laughlin’s passion for poets like Ezra Pound and novelists like Vladimir Nabokov helped spread the gospel of modernism to literature, Oliveros has presided over a similar revolution in taste in the comics world, being a key player in the rise of the graphic novel. Like Laughlin, Oliveros crafted a publishing list that bore the stamp of his sensibility, which redirected the course of literary history. Given Oliveros’s prominence, many in comics were startled when The Globe and Mail reported in May that he was stepping down as editor in chief of the company he created, handing the reigns to his long-time associate publisher Peggy Burns.

Oliveros’s decision to step down has raised eyebrows in the world of graphic novels because D+Q has always been mainly his handiwork. Moreover, the art comics companies that have made a name for themselves—RAW Books under Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly and Fantagraphics under Gary Groth and the late Kim Thompson—have all been small operations that have never had a transition from one owner to another. In the world of literary publishing, houses created by owners with personal visions such as Knopf and New Directions have successful transformed themselves into larger enterprises that exist beyond the guiding hand of their founders. If the D+Q transfer of power succeeds and the company remains at the forefront of art comics, it will mark the maturation of the alternative graphic novel form away from its artisanal roots into a structure that more closely resemble traditional publishing firms like Knopf or the post-Laughlin New Directions.

To understand the origins and achievement of D+Q, we have to return to the plight of alternative cartoonists in the 1980s.

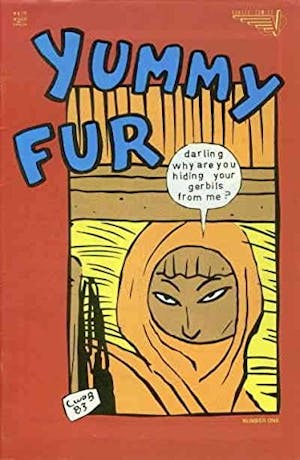

On a sweltering July weekend in 1983, residents of downtown Toronto were confronted with a strange sight. On the busy corner of Yonge and Church Streets, near the heart of the city, there stood a bare-chested 23-year old man unsuccessfully peddling a mini-comic he had created and self-published. It was an unlikely spot to sell comics. The intersection was a busy hub, the street lined with emporiums hawking cheap electronics. The cartoonist, skeletal-thin, long-haired, fierce-eyed, brought with him a hand-painted sign showing Batman and Robin depicted in the Golden-age style of Bob Kane, although the dynamic duo were inexplicably fanged and kept company with a dead rabbit. “Buy my book,” read the sign. The cartoonist was Chester Brown and the ware he was offering the indifferent public was the first issue of Yummy Fur, priced at 25 cents.

Introverted and hesitant of speech, Brown was not a natural salesman. Very few pedestrians stopped to talk to the artist. None bought his comic. Brown’s misadventures as street vendor were rooted in desperation. He was a marginal figure in 1983, an oddball doing work so fringe that there was no proper channel for it to be distributed or sold. The main reason he was selling his Xeroxed comics on Yonge Street was that he had no other venue to present his work. His scatological and sexually charged stories belong to the tradition of Underground Comix, which flourished in the late 1960s and early 1970s but had by the 1980s lost whatever cultural foothold they once had, with the network of head shops that carried them under siege from police enforcing drug paraphernalia laws. In 1983, comics were overwhelmingly a commercial art form, with family humor dominating newspaper strips just as the superhero genre had hegemony over the comic book field. In that context, to do comics that aspired to be art, cartooning that attempted to explore a personal vision rather than fulfill a commercial imperative, was the height of folly.

While the world of comics was largely a wasteland in the early 1980s, if you looked hard enough a few green shoots could still be spotted. Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly launched RAW magazine in 1980, a lavish showcase for formalist experimentation and avant garde tomfoolery that broke decisively with the ambience of underground comics. RAW would serialize Spiegelman’s groundbreaking Maus. A spate of new comic book companies (called “groundlevel” or “alternative”) emerged to serve the fledgling market of specialty comic book stores. Most of these comic book companies simply offered the same genre material as DC and Marvel Comics, sometimes with an added dose of dirty words and female nudity. Artistically, the most important of those companies was Fantagraphics, which was dedicated to renewing the tradition of underground comics. Fantagraphics launched its flagship title Love and Rockets (by the Brothers Hernandez) in 1982.

Brown was aware of these stirrings. He submitted a two-page story titled “City Swine” to RAW in 1980, which was rejected but earned him an encouraging note saying they almost used it but thought he could do better. Forgoing the unsuccessful strategy of street-selling, Brown started foisting copies of Yummy Fur on consignment to obliging bookstores and comic book stores. The comic started acquiring fans, aided by an avid zine culture that was eager for fresh talent. By dint of his perseverance and talent, Brown was able to make a career for himself. In 1986, Vortex comics, a small Toronto-based firm, started publishing Yummy Fur.

While the 1980s held promise, much of the energy was inchoate and confused. It was into this disorderly world that Chris Oliveros decided to make his mark as a publisher, bringing to bear a much more forceful and coherent aesthetic. Oliveros started D+Q in 1990 as very much a one-man (or one-family) operation; for many years the company was headquartered in whichever Montreal apartment he and his girlfriend and sometime co-editor Marina Lesenko lived.

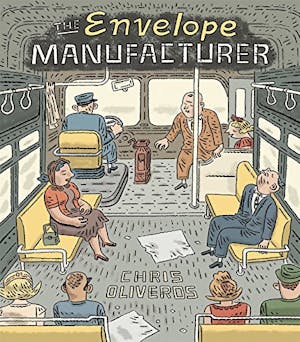

To label Oliveros as a publisher is accurate enough but doesn't do justice to the distinguishing qualities that have made him a major figure: Chris Oliveros is a cartoonist. He rarely if ever identifies himself as an artist and it is true that his output has been modest in size. Yet his graphic-novel-in-progress The Envelope Manufacturer (released in two issues in 1998 and 2006, although still incomplete) is a masterful work, a heart-rendering examination of the quiet despair and entrapping self-deception of a small business owner's quixotic efforts to keep his firm going. (Characteristic of Oliveros's unassuming nature, the first issue of The Envelope Manufacturer was released not by D+Q but by “3416071 Canada Inc.,” D+Q’s business account.)

Oliveros’s manifest skills as a cartoonist are always worth remembering because they are at the root of his success as an editor and publisher: It’s the eyes of gifted cartoonist that are at work when Oliveros examines other cartoonists, which helps explains his track record in finding talent, often at the very beginning of a career. Oliveros first made his mark by corralling his core group of artists (which included Brown, Seth, and Julie Doucet) in the pages of Drawn and Quarterly magazine—a magazine whose more distinctive editorial sensibility lifted it above the ruck of mediocre anthologies crowding the comics market. The magazine had a predilection for autobiographical anecdotes, small well-shaped tales dwelling on brief incidences. In effect, Drawn & Quarterly magazine cut a middle swath between RAW and Robert Crumb’s Weirdo, featuring work that was more narratively inclined and less formally-challenging than most of RAW but moving beyond the underground shock tactics of Weirdo. The best of Drawn & Quarterly magazine were comics that could, if done in prose form, have found a home in The New Yorker or The Paris Review.

By 1994, D+Q was already a pillar of art comics, but its financial position remained precarious. The comic book industry, rooted in hobbyist stores geared to hardcore collectors, had a punishing boom and bust economy. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, countless independent comic book companies lived like mayflies, briefly flourishing and then dying. D+Q managed to survive in the environment thanks to Oliveros’s modesty and steadiness of purpose. He resisted the temptation to expand too quickly, never published comics he didn’t believe in, and remained loyal to his core artists. Given the economic realities of the comic book market in the 1990s, Oliveros wisely kept D+Q a micropublishing firm, operating out of his home.

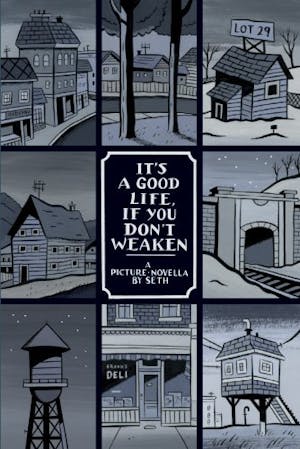

The bookstore market offered one possible alternative to comic bookstores, but it was difficult to break into. The “graphic novel” was still an inchoate form, and bookstores didn't know how to handle such books or even stock them. According to comics lore, Art Spiegelman's Maus was sometimes placed in the “humor” section of bookstores, sharing company with Garfield and The Far Side. When reprinting material from comics, D+Q was careful to package it in the form of books that looked like books, rather than thick comics. D+Q books, especially Seth's It's a Good Life, were models of attention to design, with careful attention being given to typeface, art on the insides of the cover, paper stock and all the sundry niceties of book-making. Oliveros wasn't expecting a quick solution: “I see myself as plugging away at this for years and years,” he told an interviewer in 1996. “And maybe after ten years I can look back and see we've come this far and managed this much, and maybe after I die things will be a little bit better.”

As the bookstore market opened up for graphic novels, D+Q was ready to become more than a one-man show. In 2003, Oliveros hired publicist Peggy Burns, who had previously worked for DC Comics. Along with her husband Tom Devlin, who became the firm’s creative director, Burns oversaw the expansion and professionalization of D+Q, negotiating a distribution contract with Farrar, Straus and Giroux that secured the company’s access to bookstores. Unlike virtually all Canadian publishers, D+Q does the vast majority of its sales in the United States.

Oliveros’s recent decision to step down from publishing was motivated by a sense that the company’s future was secure enough that he could resume the cartooning career that he had long side-tracked. He will stay on at D+Q as a creative editor but devote the majority of his time to drawing. After half a lifetime of promoting other people’s comics, Oliveros is ready to make his own. His published output is minuscule, and yet given his track record as a publisher he’s one of the most promising young cartoonists around.

A version of this essay appeared in Drawn and Quarterly: Twenty-five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels.