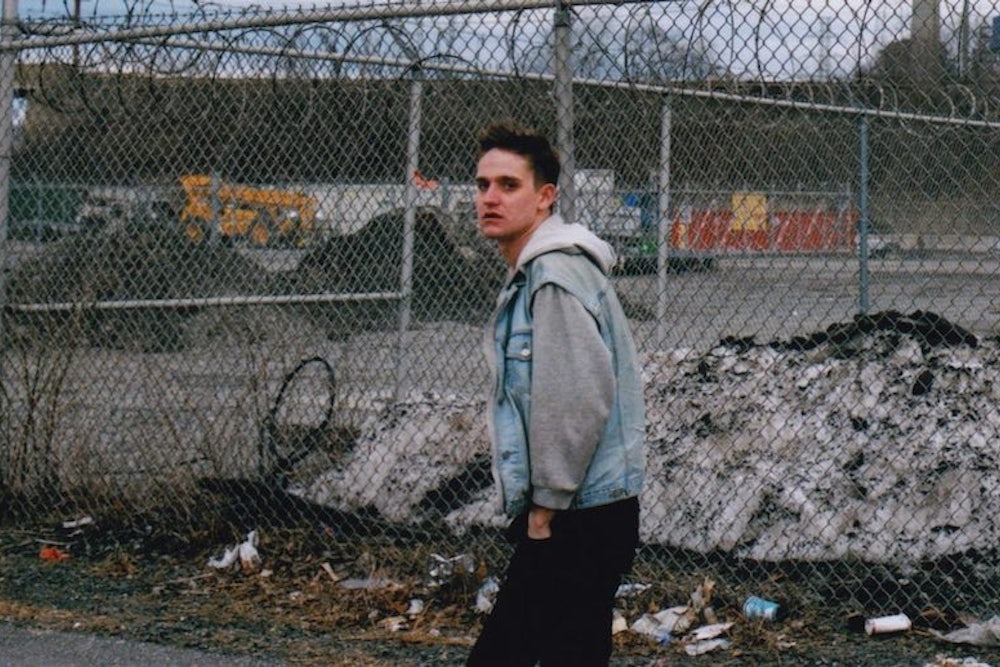

In 2003, a rapper named Juiceboxxx changed Leon Neyfakh’s life. As a high school student, Neyfakh helped organize a local punk show in a church basement, and at the last minute a friend persuaded him to add a 15-year-old kid from Wisconsin, “dotted with zits and topped with a terrible haircut,” to the bill. Though initially skeptical, Neyfakh quickly became a believer. “Juice held himself in a way that left us no choice but to take him seriously,” he remembers:

He didn’t seem angry, just possessed. With … glasses that kept almost flying off his face, he looked like a total maniac, and when his top buttons came undone and he was left shirtless, there was something almost obscene about him, with his pink little nipples and his sharp elbows swinging as he rapped. Though he didn’t have much in the way of muscle, there was something in his physical presence that made him look as though he had been built specifically for what he was doing.

On first blush, Juiceboxxx (the name is presumably a nod to Outkast’s Speakerboxxx) seems like an unpromising subject for a journalistic profile. Despite touring and releasing music for more than a decade, he is pretty obscure. He regularly plays to crowds of four, and his most high-profile achievement of late was a botched performance on a Milwaukee morning show that went viral and got him labeled “a strong contender for worst rapper ever.” His race and background are unusual for a rapper but hardly unique: in the age of Macklemore, Eminem, and Iggy Azalea, white rappers are nothing to write home (let alone entire books) about. His early tracks have juvenile titles like “The Declaration of Dopeness” and “Fast Food Anthem” and even his more mature lyrics come off, Neyfakh admits, as “trite on paper.” (Representative couplet: “Ain’t nobody gonna keep it alive/but you’ve got that dream inside.”)

It’s not easy for Neyfakh to get others to understand why he loves Juiceboxxx so much. “A lot of Juice’s output is equivocally off-putting,” Neyfakh concedes. “He shouts a lot, his voice is nasally, and some of the things he says are impossible to react to without looking down at your feet.” He has trouble even asking his New York writer friends to attend a show with him: “How would I get past the radioactive words I would have to use—‘white rapper’ and ‘rap-rock,’ chief among them—to describe what Juiceboxxx even was?”

Nevertheless, The Next Next Level is suffused with evangelical energy, and Neyfakh succeeds in making Juiceboxxx into a figure of intrigue. He does it initially by detailing the heights (and depths) of his own personal infatuation, so that we wonder what Neyfakh, a former ideas reporter for the Boston Globe who now works at Slate, sees in this guy, and strain to see it too. In many ways The Next Next Level is more memoir than profile. We hear about the young Neyfakh’s own musical ambitions, and his clashes with his Soviet immigrant parents. “American culture, by and large, struck them as crude and vulgar,” Neyfakh says, and Juiceboxxx—“the image of ‘shpana,’ a Russian word that translates only to ‘thuggish punk’”—exemplifies that crudeness.

For the teenage Neyfakh, though, Juiceboxxx represented a kind of passion and authenticity that he felt was lacking in his own life. Over the years he seeks to emulate his idol; in college, he briefly considers stealing his shtick and becoming a rapper himself, a memory that now fills him with intense embarrassment. As an adult journalist, he still catches himself “contorting himself in order to impress” him: “I worry that I’ll call him ‘man’ when I first see him, and that I’ll end up dropping my g’s in that way I hate, and pretend I’ve heard of things I’ve never heard of.”

The conceit of The Next Next Level is that Juiceboxxx and Neyfakh are doubles of one another, “two guys colliding with each other at a crucial moment, and … using one another as mirrors.” Ultimately, though, Neyfakh may not go far enough in his identification with his subject. He insists throughout on classifying them as fundamentally different types of people, in a way that begins to feel like protesting too much. “This little book … is about the difference between being an artist and not being one, and the confusion many people feel as they try to figure out which one they are, or should be, or wish they were,” Neyfakh writes in a brief introduction. And though this binary opposition between artist and non-artist (elsewhere, “genius” and “critic”) is finessed, it’s never really abandoned. Juiceboxxx, for him, is an ideal representation of the artist, free of self-consciousness and driven to create; Neyfakh himself is a critic, a mere “secondary source.”

As theories of creativity go, this is a pretty schematic one, and one that will only take us so far in understanding actual human beings. Tellingly, it’s Neyfakh, not Juiceboxxx, who insists on the absolute otherness of the artist. When Juice tells him that “I don’t put myself in opposition to anybody else,” Neyfakh’s reaction is characteristic: “I badly want him to acknowledge that he and I are in fact very different. And also to feel sorry for me. And also to tell me it’s OK that I am who I am.” Neyfakh’s existential anxiety at such moments is palpable, and the closer he gets to the reality of Juiceboxxx’s existence—his life as a person, not just a musician—the more it seems to flare up. When Neyfakh helps Juiceboxxx land some freelance writing gigs, he begins “to suspect that I had inadvertently ruined everything”: “I hated myself for having played a role in making him more similar to me.”

It’s significant that Neyfakh fears Juice would be “ruined” by earning a steady income. The Next Next Level makes it clear that Juiceboxxx makes only a meager living from touring, which he supplements by writing ad jingles for corporations like Microsoft, Target, and Exxon. When Neyfakh talks about the difference between him and his friend, he often does so in economic terms, emphasizing the safety and security of his own career as opposed to the hand-to-mouth anxiety of Juiceboxxx’s. “Where I, like many, used to dream of becoming an artist, I have instead turned out to be a professional: a reporter with a solid career writing feature stories for a newspaper,” he muses, and, later, wonders “what [Juiceboxxx] must think when he looks at me, a guy who’s never had anything but a ‘real fucking job’ in his life, and at this point, having achieved relative prosperity and a generally comfortable existence, very obviously never will.”

But is there really such a vast gulf separating Juiceboxxx’s precarious existence in an unraveling industry from Neyfakh’s “real fucking job” writing for a newspaper? What makes Neyfakh so sure he’ll “never” have anything else? At such moments, his confidence in the absolute division between the middle-class professional and the struggling artist comes off as outdated and a bit naïve. Joseph Mitchell, writing fifty years ago in The New Yorker about the itinerant bohemian Joe Gould, could see Gould as a kind of alien species, and take for granted that his affluent readers would see him that way too. But today the line between starving artist and working journalist is a lot thinner, and Neyfakh’s book would have been a lot more powerful for recognizing this.

The cumulative effect of The Next Next Level is to make you more curious about Juiceboxxx, even if you can’t see quite why Neyfakh idolizes him. There is room for many pages on the high school bands Neyfakh played in and theories about American pop culture, but we get surprisingly little biographical background on the book’s ostensible subject: We never learn Juiceboxxx’s real name, for instance, or anything much about his family or early life. He makes frequent references to his struggles with depression and other emotional problems, at one point confessing that making music “has just been a really weird attempt at me not killing myself for twelve years.’” But Neyfakh never follows up on these intimations, perhaps because he sees such darkness and misery as intrinsic, like poverty, to the creative life.

There is a lot to recommend The Next Next Level, despite its flaws: the book is light on its feet and often very funny. (Neyfakh is especially good on the subject of his own self-consciousness, as in this careful disquisition on why he doesn’t like dancing: “Part of the problem might be that it strikes me as deranged and unethical to be moving around in ways that basically force the people in my immediate vicinity to imagine me having sex.”) And Juiceboxxx’s yearning to improve as a performer, and to make a “transcendent record,” is moving, whatever you judge his prospects of accomplishing those goals to be. As for Neyfakh, he hasn’t quite written a transcendent book, but he’s written a good one, and unlike his friend he has room to develop. At one point, Juice observes that “what’s so crazy about music, is that being twenty-seven puts you in a weird zone—like, you’re not young anymore. But in so many other creative disciplines, I would be just starting out.” The tragedy of Juiceboxxx, such as it is, is that it may already be too late to reach the heights he imagines for himself. For Neyfakh, there’s still plenty of time.