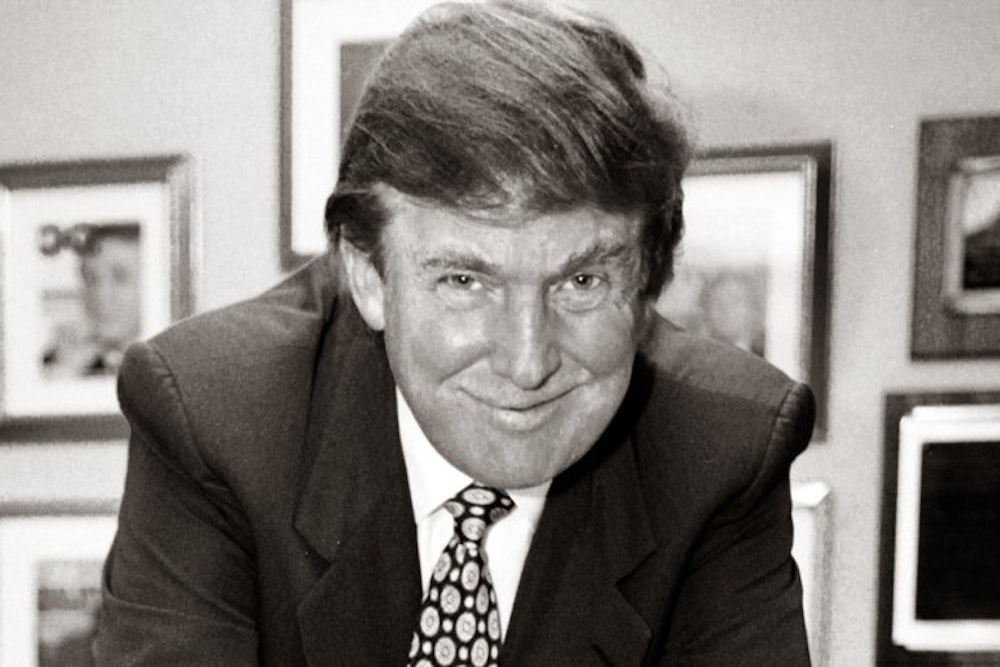

“While I can’t honestly say I need an 80-foot-long living room,” observes Donald Trump of his triplex apartment in Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, “I do get a kick out of having one.”

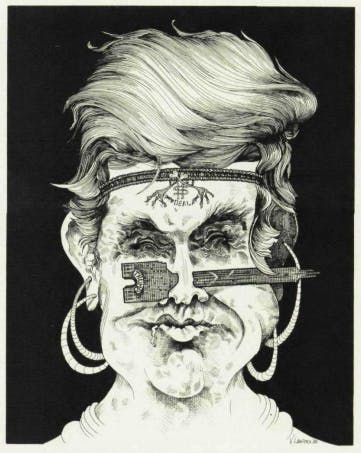

The distinctive thing about this kind of appetite is its contempt for sufficiency. What is enough is precisely what is not enough: how much better to have nothing than to have merely what you need. But appetites are mediated emotions— they learn what is worth having by seeing what others have—and are therefore permanently vulnerable. Though he may feel that he has successfully outstripped his needs today. Trump must live in dread of the appearance tomorrow of the man with the 90-foot living room.

This is a funny kind of pathos, like the pathos of King Midas, but it is the darkness in the glitz of Trump’s autobiography, and in the glimmer of contemporary Manhattan. New York has always been a supermarket for every appetite; New York in the ‘80s has started to look like a specialty store for those appetites that can be satisfied only with things.

Almost nothing about Donald Trump, apart from the magnitude of his ambition and the fact that it expresses itself in real estate, seems to evoke Manhattan. He is an alien from the outer boroughs, the big spender with the sports fan’s vocabulary and the wrong haircut.

Sophistication, the quality Manhattanites plume themselves on, is the quality he most despises. His idea of excess is a suit that’s cut just a little too well. But there are a few qualities that make Trump a representative man of his town and his time: he consumes aggressively and conspicuously, he understands the value of self-promotion, he is contemptuous of those who are unsuccessful.

The tale of Trump’s triumph—the triumph of Trumpery—is well known by now, for its hero is not shy of publicity. Trump’s father, Fred, was a winner in the hard business of building and managing g low- and middle-income housing in Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island. Donald learned development at his father’s side—reluctantly taking time off to get an undergraduate degree at the Wharton School—and then set out, with an Oedipal design that could not be more obvious and that is one of the genuinely touching things in his story, to do what Fred could not do: build the Big Building in the Big Town.

Trump’s strategy was two-pronged. He went after property that was too vexed for others to pursue. And—not yet 30 and with nothing to show for himself (the rap on Trump in those days was that he was all talk; now many people would gladly settle for the talk)—he hired Howard Rubenstein, one of the most successful public relations experts in the city, and began beating the drums. He has been pounding away ever since.

“Trump: The Art of the Deal” (fresh drumroll, please) is more forthcoming about the first wing of the Trump attack than it is about the second. The reason goes to the dark heart of Trumpery: the book is itself a craftily designed piece of public relations. That a businessman should thus use himself as a sales gimmick is hardly a crime against literature. But “The Art of the Deal” does deserve at least a warning label.

Still, the story of Trump’s progress—told, to be sure, as the unfolding of a manifest destiny, and with absolute deference to the instinctive genius of the Deal-maker himself—is unquestionably compelling. Tony Schwartz, a media critic now at New York magazine, has crafted an attractive style of braggadocio for his employer—one that preserves the loudness of the Trump voice and the thrilling simplicity of the Trump philosophy, but that mutes the bullying, schoolyard quality that comes through in press conferences and television interviews.

Trump is a real estate garbageman. He can smell opportunity in distress. His recreational reading in college, he tells us, was the listings of Federal Housing Authority foreclosures. And all his big deals—the Grand Hyatt, Trump Tower, the Atlantic City casinos—were put together from properties other people had to get rid of. When Trump made his move to Manhattan in the mid- ‘70s, the market was scraping the bottom. The city’s illness was Trump’s leverage.

People were willing to listen to Trump because nobody else was calling. He sought out one of the sickest patients in the city, the bankrupt Fenn Central, struck up a friendship with the people in charge of selling off the assets, and started buying options on its properties. These included the West Side railyards at 34th Street (Trump eventually convinced the city to purchase the land for a convention center, picking up a broker’s fee of about $800,000); the West Side yards at 60th Street (this is the land Trump finally purchased in 1984 for Television City); and the Commodore Hotel on 42nd Street, next to Grand Central Station.

The Commodore deal is the locus classicus of the Trump method. It was in a sense the Ur-deal for the ‘80s as well, the deal that showed how government and private enterprise might work hand in hand to create more luxury accommodations than the city could possibly need or its indigenous population possibly afford. In 1974 the Commodore was a deliciously distressed parcel. It belonged to a bankrupt corporation; it owed $6 million in back taxes; it was losing $4.6 million a year with an occupancy rate of 33 percent. Trump agreed to purchase an option on the property for $250,000 from Penn Central, which, having just thrown $2 million into a fruitless renovation, was on the verge of closing the hotel.

Trump had a few problems, though. He was 27 years old. He didn’t have a quarter of a million dollars he could afford to part with; he knew nothing about hotels; and he had never built a thing in Manhattan. He had to keep Penn Central committed to the option without actually putting any money down (he instructed his lawyers to stall) while he tried to convince a bank that he could develop property in an area most people had given up for dead. He hired an architect—Der Scutt, who eventually designed Trump Tower—to make drawings on a characteristically grandiose scale. And he got the Hyatt organization to agree to manage the facility. But he still needed not only $10 million to buy and $90 million to renovate; he needed $250,000 to purchase the option.

In 1975 rescue came in the form of the Business Investment Incentive Policy, the city’s offer of tax relief for new development. Trump was first in line, and he asked, as he puts it, “for the world”— an agreement that, boiled down, meant that in its first 40 years he would pay, on a graduated scale, property taxes on the hotel at a rate based on the property’s assessed value in 1975. He got what he asked for. By the time the hotel opened as the Grand Hyatt in 1980, the city’s economy had turned around, and so had property values in midtown. It has been estimated that the tax abatement Trump received was worth $100 million.

Among the details of the way Trump orchestrated his pitches to Penn Central, the city, and the banks and contrived to pit each player against the others—all without committing a single dollar of his own to the property—one stands out. During negotiations over the “incentive,” the city’s Board of Estimate asked to see Trump’s completed option agreement with Penn Central. Trump didn’t have a completed option agreement, of course, since he didn’t have any financing. So he sent along a copy with only his signature on it. Nobody noticed.

In his short career Trump has turned a lot of tin that people were eager to be relieved of into some very expensive tinsel. The obvious question is whether buying real estate in New York and New Jersey in the ‘70s and converting it into cash-flow businesses in the ‘80s wasn’t shooting fish in a barrel. A lot of people made money that way; Trump just shot at the biggest fish. Trump was supposed to be worth $3 billion before the market and the dollar started convulsing. But who wants to be in luxury housing and gambling when times go bad?

“When bad times come,” Trump told Barbara Walters recently, “I’ll get what I want.” But he has to do some fast positioning, because the tide that carried him to his fortune is turning, and the very publicity that helped lift him up has started to weigh him down. This is where “The Art of the Deal” makes its interesting contribution to the Trump image.

Trump has always understood that it is crucial in New York to make as big a noise as possible—and that (so long as you have a Teflon ego) it doesn’t matter whether the response is good or bad. “Even a critical story, which may be hurtful personally, can be very valuable to your business,” he confides in the book. Thus the fanfare about “the world’s tallest building”: it attracts attention, and hence prospective tenants, and it makes a colorful bargaining chip, to be cashed later on down the line for community board approval and for zoning and tax concessions. But the flamboyant lifestyle—the 80-foot living room, the 118-room Palm Beach mansion, the yacht that once belonged to Adnan Khashoggi—is not good advertising for A man in search of a tax abatement. Not in times when Mandevillean virtues such as greed are supposed to be going back into the closet.

The Art of the Deal tries to change the picture somewhat. It skates quickly over the big houses (the 45-room “weekend” mansion in Greenwich, for example, is not mentioned) and the expensive toys—all the stuff of “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” profiles. It ignores Trump’s contributions to the foreign policy debate—his offers to negotiate an arms control treaty a few years ago and his more recent exhortations about making japan pay for its own defense. It is even modest about certain of the Trump acquirements; you would never know, for instance, from the disparaging things said here about academic credentials, that Trump graduated first in his class at Wharton. But the book is not the portrait of a man and his work. It’s much too smart for that. It is a weapon in the continuing public relations war that is Donald Trump’s way of doing business.

Today the enemy is city hall. The message the drum beats out over and over is that Trump didn’t take all the things he owns; they were handed to him on a platter by a shortsighted and incompetent city government. “Competence” is the book’s buzzword. It is worked into every sentiment. (My favorite: “There is nothing to compare with family if they happen to be competent.”) The Wollman Rink affair, in which Trump took over the renovation of a public ice rink the city had turned into a carnival of delay and disaster, is recounted in every last detail. We learn the right (Trump’s) and the wrong (the city’s) ways of pouring concrete; we hear of two separate occasions on which landscaping jobs were scandalously botched by Park Department workers. What was “at the heart of this whole sad saga”? “Incompetence, plain and simple.”

The stakes in the Television City project are high. The property is squeezed between two transportation facilities that are already obsolete, the 72nd Street subway station and the West Side highway, and whoever hopes to build on the site will have to make a hefty contribution toward their improvement. The Upper West Side has already been developed very close to the limit of what its residents will tolerate—and its residents are constitutionally not fond of developers. It is in Trump’s interest to make his case seem the case for jobs and prosperity, not for greed and glitz, and to make the city’s case seem a case only for waste and delay. “When bad times come, I’ll get what I want” means, “Deal with me now, because look what the city gave me when it was desperate.” True enough; his book contains many proofs. But that was when he was hungry. Now he’s fat. The book is here to tell us it’s not his fault.

In Donald Trump the world of New York real estate touches the world of the arts. For the ability to make it all look like an accident while you are promoting yourself frantically has become a necessary accoutrement of genius in New York’s fast-track high-yield high culture. Tama Janowitz has managed to cultivate both an appearance that is a parody of East Village “look at me” contemporaneity and a gee-whiz manner that says. Why is all this happening to me? “Just someone who wants to be left alone with her typewriter” is the sort of thing you’ll hear her say on the David Letterman show. This is a style of self-promotion that has worked before. It is the trademark style of Janowitz’s mentor, Andy Warhol. What one wants to know, of course, is: Is Tama Janowitz really happy?

What is happening to Tama is this. In 1986 Crown Publishers gave her a modest advance on a collection of stories, and put her to work merchandising them. Among other stunts, she starred in the first “literary video,” was promoted as a wacky personality to feature writers and TV talk-show producers, and was sent into Lutece and The Four Seasons to hand out copies of her stories to unsuspecting diners. The book, of course, was “Slaves of New York”, a compendium of wan tales about lower Manhattanites who suffer the tortures of affectlessness (there is no literary disease more affecting). Some of the work had appeared in the New Yorker; it all has the unmistakable aura of the M.F.A. The hype worked. “Slaves of New York” made the best-seller list for a shining moment or two, and brought Crown a tidy sum for the paperback rights.

The odor of academia is not so surprising. Janowitz has a B.A. from Barnard, an M.A. from Hollins College in Virginia, and an M.F.A. from Columbia; she has studied at the Yale School of Drama. She wanted to be, apparently, a serious writer. Then she met the people from Crown. What they asked her to do was, she told a reporter from Manhattan, inc., “humiliating”:

But I had to decide [to do it]. Because I’d been sitting in this room being broke year after year. There’s a breaking point where you say, “I’ve just gotta get out there and say, ‘Hey, 1 wrote this book, and I worked hard on it. And read the goddamn book!’ “ So it’s unseemly behavior. Screw that.

She was 29. It’s tough not making it in New York.

Now, having placed its author in a series of magazine ads for Amaretto and Rose’s Lime Juice (where she appears with party animal Arthur Schlesinger Jr.), Crown is rushing to keep up with its own bandwagon. It seemed there was nothing doing in the typewriter, so they looked in the drawer. There they discovered “A Cannibal in Manhattan”, a novel Janowitz had written before celebrityhood was thrust upon her but that she had been unable to get published. This did not perturb the people at Crown, presumably since the criteria previously applied must have been merely literary.

The novel is such a desultory affair that if 1 gave a plot summary I might be accused of overanalyzing. What one expects from the title, of course, is, first, the Martian effect: what New Yorkers take for granted the cannibal finds exotic. And, second, a bit of modernist irony: the “primitive” is more “civilized” than “civilization.” These literary standbys have become so wrung out, though, that Janowitz can barely summon enough inventive energy to pay them lip service. This sort of thing is the best she can come up with (the cannibal is flying from his island home to New York):

A while later another stewardess appeared with marvelous celebratory feast-trays, one of which was handed to each person. Oh, how delightful! For there was a little mer\u with each tray, and on my dish was something called the hot pastrami sandwich: this consisted of a very hard roll, soggy in the center and topped with tiny seeds like gnats, while within were some curious greasy strands of meat. And there was also a salad, which consisted of some pale-green slimy leaves and a tiny red rubber ball. . . . There was also the cake. . . .

A kind of humor is intended, 1 suspect; it’s a humor for the ‘80s. It’s the smart person being stupid routine—the routine David Letterman has perfected for making fun of people who aren’t David Letterman. The joke is that the cannibal’s making-it-strange descriptions and Montaignesque observations on the savagery of the civilized locals are funny not because they’re witty or pointed—that kind of humor is out of style. They’re funny because they’re dumb.

Tama looks miserable on the Letterman show. “Humiliation” is a strong word, and she may have meant it. Of course, it’s hard to tell with people like Janowitz and Warhol and Trump—people who do a striptease with their personalities. “Is this the real me, or am 1 just selling a product?” they seem to be asking again and again.

And then they ask us to feel sorry for them. In the glossy publicity packet that comes from Crown with the review copy of “A Cannibal in Manhattan” is a letter headed “Dear Producer.” Here are “just some of the ideas,” the letter says, “of a program that could feature Tama.” This idea sounds especially promising to me: “A profile of a young American author who after struggling for a number of years suddenly finds herself in demand by the public and the media.. .. How does one deal with the pressure to please as well as the pressure to produce another best-seller?”

If the Trumps and the Tamas of the world are important, on the principle that if we did not have the spectacle of excess we would not know why moderation should be counted a virtue, then the boom economy of the ‘80s has provided many cautionary examples. Among the choicest are those described in New York Confidential. Sharon Churcher, a journalist formerly with the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post, now at New York magazine, has gotten the story as no one else has. New York Confidential is the story Manhattan, inc. and Vanity Fair—magazines that flirt coyly with the world of the Roy Cohns and the Claus von Bulows and that position themselves in relation to their subjects somewhere comfortably between sycophancy and contempt—are afraid to tell you.

The charity balls and the Eurotrash “titled” designers and the services that provide celebrities for your parties may not have received quite this sharp a treatment before, but they are familiar objects of satire. The prime piece in Churcher’s book is the report on the financial condition of Manhattan’s churches. This is a real estate story like nothing in Trump. Trinity Church on Wall Street, for instance, owns 40 commercial properties and has a stock portfolio worth $50 million, yielding an income of $25 million yearly, of which $2.6 million is given to charity. Its rector has a salary of $100,000 and a church-owned home on the Upper East Side. (“There’s such money here that you really wouldn’t want the man at the top to be worried about money,” explains a spokesman.) It is currently selling spaces in its mausoleum overlooking the Hudson River for prices that range from $1,250 to $20,000. St. Bartholomew’s on Park Avenue, which had been trying to sell its air rights to a developer until the Landmarks Preservation Commission squashed the deal, spends $100,000 of an annual budget of $3.2 million on charity. The rectory is a 13-room apartment on Park Avenue.

But the best is the story about the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, which sits appropriately across the street from Trump Tower. It seems that five or six homeless people had taken to using the steps of the church after hours as a refuge from the cold. The security guard was instructed to chase them away. “They were using the place as bathrooms,” explained a church staff member, “causing corrosion to the wood and stone, and there were potential fire problems because people were building little homes of cardboard and using little candles.” Several months later, with a lucrative sale of its development rights in the works, the church relented and announced plans to provide six cots, five nights a week, for the homeless. But the pastor first had a matter of principle to settle. “Presumptions that the church should be trying to improve housing for the poor. . . . The presumption that the church should be small and impoverished. These are hidden presumptions that I see all the time,” he told Churcher. “Are you housing the homeless in your home? What’s the Empire State Building doing to help the homeless . . .? Why should people just pick on the churches? There’s a fairness element here.”

The world of those with too much and the world of those without anything have sometimes appeared to be the only worlds in contemporary New York. The dichotomy, in part by virtue of being reported on endlessly in the very places that celebrate success (“The Young and the Homeless“ ran the headline on a picture story in a recent issue of New York Woman, a magazine for young professionals), eventually became a part of the mentality of the boom. Having is the only happiness, was the message. All else is misery and madness.

One of the attractions of William Geist’s “About New York” column in the Times was that it often seemed the only feature writing in the city that reported on the happiness of having enough. His stories fed the almost forgotten illusion of an eternal New York, a world of ordinary people of ordinary appetite, a world that existed before the designer clothes and the yuppie restaurants and the superstretches invaded, and that would go on existing long after those ephemera of the bull market had departed. Geist has since left the paper to appear as a correspondent on “CBS Sunday Morning.” “City Slickers” is a selection of his work at the Times.

On the face of it, it’s a questionable idea for a book. The premise is unspeakably mundane: New York is one c-r-a-z-y town. The method is a local news standby: What does the man on the street think of all these goings on? But the execution is impeccable. And the moral sentiment is admirable; it is even, in its way and times, brave.

Some of Geist’s pieces were scoops of a sort. The story of Kyu-Sung Choi, the Korean immigrant who wanted to open a deli on Park Avenue but was opposed by the local aristocracy, was Geist’s. So was the story of Eugene Lang, the millionaire who, on the spur of the moment, announced at a sixth-grade graduation in Harlem that he would pay the college tuition of any child in the class who finished high school (“maybe the greatest speech ever made,” one student called it). So was the story of the bidding war for rights to the murder of Jennifer Dawn Levin—the preppy murder case. Put Geist’s strong suit is the non-story—chatting with customers at the La-Z-Boy Showcase Shoppe in Queens, for instance, or sitting in on the deliberations of the powerful Food Committee at the Hebrew Home for the Aged in Riverdale.

The message his subjects deliver is deeply subversive of the ethos of the age. The La-Z-Boy customers, interviewed on the day of the New York marathon, are entirely happy without the narcissistic rigors of yuppie “fitness.” Bernie Spitz, the Hanger King, sums up his career in tones that ring truer than anything in Trump’s autobiography: “It’s been a wonderful life. There’s never a dull moment in the hanger business, as you can imagine!” Charles Richman, who draws up an annual list of the world’s best-dressed men, on Pope John Paul II: “He just wears religious garb, of course, but he looks marvelous in it, doesn’t he?” Albert Golub, 50 years in the coat-checking profession: “One of the finest things you can do in life, I believe, is check your coat. In this way, you don’t have to sit on it.”

The challenge in the man-on-the street genre is to get the quote that’s funny without making fun of the person who’s quoted. The risk is that the reporter will get caught winking at the reader when the subject’s back is turned. This is especially an ‘80s temptation: in times when the well-off feel a little too guilty to laugh at each other’s indulgences, the ordinary becomes campy. Geist avoids the danger in his columns; he conveys a real affection for his subjects and, when called for, a real anger on their behalf. His column on the Park Avenue deli aroused the city.

If there is in fact something that seems forever about the city, something certain to outlast the greed and the shame, it’s the image we hold of it in our minds, a ghost made of steel and concrete and limestone and brick—”the city of frozen fountains.” “New York 1930” is a stupendous record of the creation of that New York, the physical city that, like a mountain range or a desert, seems as much a thing imagined as a thing seen and touched.

It is fitting that this architectural history should appear in the same year as “The Art of the Deal.” For it reminds us that the city of the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center was not simply the reflection of a phase in the history of architectural taste, but the product of conditions that no longer obtain. The city most people think of as the essential Manhattan is not so old, and it was not so inevitable. There is no greater mistake for those who cherish it than to imagine that it is eternal.

The New York skyscraper is one of the most distinctive buildings in the world. When it first began to appear on the skyline in the 1920s, it generated enormous enthusiasm and enormous dismay—those were the days (they now seem long gone) of architectural utopianism. Some observers (the enthusiastic ones) even felt that a New World style had-been established, and extended comparisons were drawn between the modern skyscraper, with its multiple setbacks and towers, and the Mayan pyramids.

But the design affinities were purely accidental. The appearance of the ‘30s skyscraper, as the admirably restrained text by Robert Stern, Gregory Gilmartin, and Thomas Mellins explains in great detail, was determined by three conditions external to aesthetics. The first was the zoning requirement that tall buildings have setbacks to allow sunlight to reach street level. The city’s insistence on maximizing sunlight had nothing to do with concerns about the mental wellbeing of the citizenry; its motivation was economic. Less light on the smaller structures surrounding the skyscraper meant lower assessed values for those properties, and hence lower taxes.

The second consideration had to do with the economics of the developer. The setback requirement meant that for a tall building to be profitable after construction costs it needed as big a base as possible. Thus the massive, cathedral like foundations of colossuses like the Empire State Building and 30 Rockefeller Plaza. On the other hand, since air conditioning had not yet been developed, office space could be sold at a premium up to a depth of only 30 feet; a deeper office was harder to light and, since it was farther from a window, harder to cool. Which is why the classic skyscraper tapers—elegantly when seen from the sky, dramatically when seen from the base—to a needlelike tower.

In 1932 Frank Lloyd Wright complained that “the skyscraper envelope is not ethical, beautiful, or permanent. It is a commercial exploit or a mere expedient. It has no higher ideal of unity than commercial success.” He was entirely right. And he would be right today. Trump Tower, as Ada Louise Huxtable pointed out in a review of the building’s design in 1979, looks like nothing so much as the zoning concessions Trump received to build it. The width of the entrance, the size of the atrium, the height of the tower are all functions of what the city required or was willing to give up, and of what met Trump’s commercial purposes most profitably. It is pointless to expect developers to build for other reasons. What “New York 1930” tells us is that though the developers won’t change, the conditions can be made to.

There is one other ingredient in ‘30s architecture, though, one that does not reduce to a costing out and that is not so easy to re-create. It has to do with an idea people once held about the uses of the city. The authors of “New York 1930” call this idea “urbanism.” It is a sense a city somehow expresses and feeds about the public side of private life, about the enrichment that comes from sharing the spaces of one’s pleasures and pains. This is precisely a sense that luxury apartment towers in the commercial center of the city violate. Trump Tower, the Museum Tower, the absurdly overscaled hotels beginning to appear on Times Square—these are advertisements for exclusivity. Private appetites only satisfied here, they seem to say to the man and woman on the street.

When you stand on a subway platform in New York, or on a street corner, or wander through one of the public spaces in private buildings that is not given over, like the atrium of Trump Tower, to a frenzy of upscale shopping, you rarely hear strangers talking to one another—about the events of the hour, or the fate of the Yankees, or the health of the city on that particular day. Occasionally a cabbie will bring up those subjects; they all live in the outer boroughs, of course. But Manhattan is more than ever a place of people with their heads down, the better to keep their inner fires burning. “Civic-mindedness” is one of the names for the spirit of New York 1930. How quaint that word sounds in New York today.

We make the city we are, but we are not the only ones who have to live in it. Though the market may slump and the balloon may shrink, though we may wake up to find that, as Newsweek announced, “Greed Is Out,” though we may get the homeless off the steps of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church and under their own roofs, the physical residue of the ‘80s remains and becomes the skeleton of future imaginings. Literary videos will go, and red suspenders will go, but Trump Tower will remain, a monument to appetite.