I, Elspeth Reeve, am the manliest journalist in the world. That’s not something I go around thinking about all day, but recently Mark Judge wrote a semi-viral article titled, “Where Have All the Manly Journalists Gone?” I am here to answer that question.

Judge’s essay for Acculturated.com, “an online magazine about the virtues and vices of pop culture” with a politically conservative slant, drew some attention when he savvily tweeted it at many journalists. It is a tailored-for-Twitter version of a longstanding anxiety—ex: “THE SISSIFICATION OF AMERICA CONTINUES APACE.” Judge, who has written a book titled A Tremor of Bliss: Sex, Catholicism, and Rock 'n' Roll, wonders what happened to the burly old guys with alcohol problems who wrote about big wars: “Ernest Hemingway. Ernie Pyle. Jack London. Christopher Hitchens.” The article is illustrated with a photograph of Hemingway using a typewriter outdoors, with rugged mountains behind him, while wearing a leather vest and pomade in his hair, which clearly was not staged for his own vanity, because that would be unmanly.

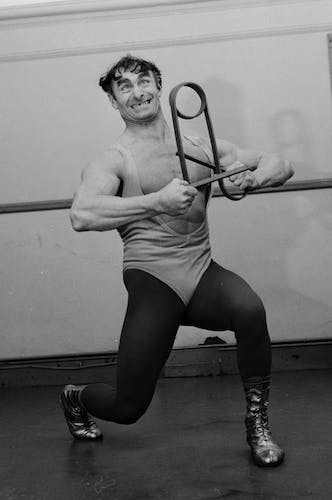

In the good old days, there was an “intense physicality” to reporting, Judge writes, and “journalism was a job of grit and hard effort, like boxing.” These days, we type things on computers, like pussies.

For years various commentators have lamented the vague sissification of the United States—Bill Maher on our "feminized country" where "feelings are more important than facts"; a Wall Street Journal opinion video decrying "The Wimpification of America" because the president wouldn't let his hypothetical kid play football—so it’s refreshing that Judge has clear criteria for manliness. “They had been fishing for real, had been drunk and gotten into fights, had slept with women, hunted sources, and dodged soldiers in hostile countries,” he writes. Done, done, done, I’m hetero, sure, and close enough? (I’ve confronted hostile soldiers in foreign bars.)

And that brings us to the most important topic in this discussion: me. Me and my manliness. Let’s start by placing my workout routine in the context of a contentious political debate. When the Pentagon was considering allowing women in combat roles in 2013, many weak-armed pundits claimed that females could not handle the tough manly workout required of this job. But I knew the truth.

Let’s think critically about this for a second. Army infantrymen are paid to work out. It’s part of their job to work out every day—in groups, in unison, with essentially a personal trainer, shouting words of encouragement. They even have cute little moisture-wicking outfits, one for warm weather and one for cold. So who is more manly: The men who get paid to jog together in matching athleisure on a balmy north Georgia morning, or the writer who rises at 5:30 a.m. to run, unpaid, in the darkness through a frozen Brooklyn park?

All I’m saying is, the manly thing to do here is to ask questions. Also I am saying that it is me, I am the manliest.

When people say rude things to me on Twitter, I click on their avatars and evaluate whether I could beat them up. I could beat them all up. I can because I am manly, and they are tiny impotent males who tweet with tiny delicate fingers. Mark Judge agrees that Twitter is unmanly, and that is fine. This did not stop him from tweeting his article at many journalists as well as Russell Crowe, the Australian actor who has played many manly men.

About two miles into my daily run, I climb the brutal elevation of the Manhattan bridge, and in my glorious endorphin-fueled reverie, I behold the phallic skyscrapers of the New York skyline thrusting toward the raw masculine sunlight. It is a sacred moment, heightened by that new Jamie xx album, which is manly in its goodness without being unmanly in its pretentious obscurity. In these moments, my thoughts wander, often back to Twitter, and to all the males on it that I could beat up so easily.

Then I run home and do a sick ab workout, like just killer and raw. You would seriously puke. Mark Judge would also puke. It takes way less manliness to wear cargo shorts than it does to wear a crop top. A crop top demonstrates willpower and tenacity—your strength to bend nature to your will in the face of the cupcake platter in the office. Pain is weakness leaving the body. You can hide a lot of weakness with cargo shorts.

“There was also a correlation between the roughness of the reporter’s life and the quality of his work,” Judge writes. Here again, I win. I am from the most manly part of America: the South. I used to work in a factory, which is one of the manliest jobs you can have, in Tennessee, which is one of the manliest states. I put stickers on desktop PCs, which are more manly than Macs. I was the best, because being the best is manly. I worked overtime on my night shift, because work is manly, and also because overtime was mandatory, because humane working conditions are unmanly. At family reunion, I have eaten squirrel dumplin’s. Eating anything with an apostrophe is manly; eating a rodent is manlier.

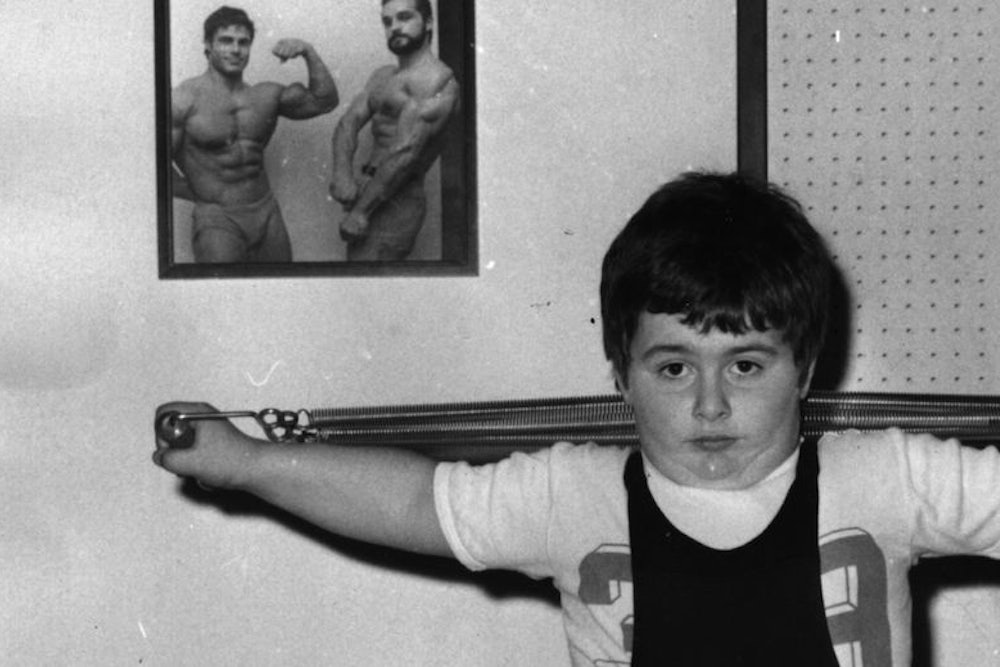

I have been working toward maximal manliness my entire life. But I was already pretty manly as a tiny pale fourth-grader. That was when I broke my elbow so badly my doctor said I’d never straighten it again. When my cast was removed, I hung from my crooked arm on my backyard trapeze amid searing pain for weeks until it slowly straightened out. I can now hyperextend it, because that is what manly men do: they hyperextend their elbows.

Judge writes:

While newspapers and magazines have always attracted many types of writers, the most notable journalists often gained fame and recognition through their bravery in the face of extreme conditions. Hemingway and Pyle were war veterans. Hunter Thompson took on the Hell’s Angels and paid for it with a severe beating. Christopher Hitchens earned his scars through decades of dangerous stories and by challenging the orthodoxies of the culture.

Later Judge adds, “Being in danger, or even knowing that someone you wrote about might want to confront you physically, made you care about honor and accuracy.”

The Hitchens example helps separate the manly wheat from the chaff. The late Hitchens was of course a beloved Kissinger-bashing atheist columnist who got in hilarious fights with cable news idiots. But let’s not forget that one way he earned his scars was writing a hit piece on Mother Teresa. If you wanted to find a target who would almost certainly not confront you physically, you would pick an elderly nun.

Here again, allow me to swoop in with a tale of manly triumph. I’ve had an angry soldier, wasted on his first night back from Iraq, scream in my face, “I DON’T KNOW WHETHER I WANT TO PUNCH YOU IN THE FACE OR FUCK YOU!” while his buddy stood behind him, saying, “Hit her hit her hit her!” Don’t worry kids, he did neither. I talked him down with exquisite manliness. His friends apologized to me later. His time in Baghdad had been difficult.

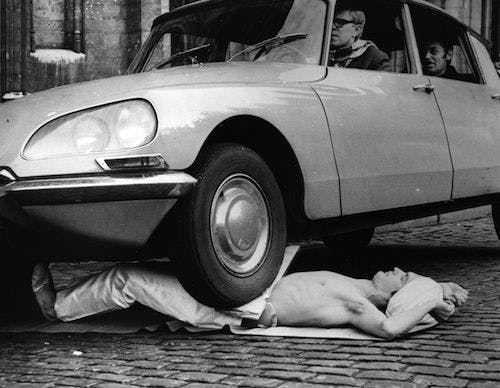

The military, the purest source of manliness in our culture, is where the many great journalists hailed by Judge got their best stories. Let’s not forget that the war reporter doesn’t have to actually kill anybody. One of the saddest things I’ve ever seen is a thriving BMW motorcycle dealership on an Army base where thousands of infantrymen were stationed. These guys had gone to Iraq, maybe multiple times, and had fired their weapons, and been shot at, and seen mutilated dead bodies—and they still had something to prove.