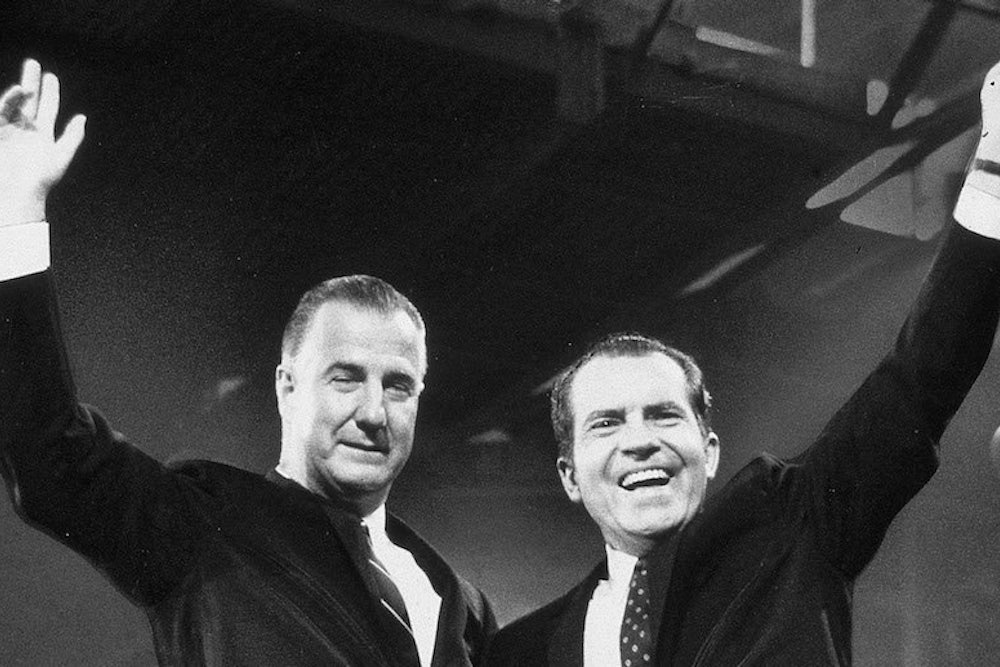

I like speaking before senior citizen groups about my research on the American culture war. Seniors almost all recognize the PowerPoint image of the late Spiro Agnew, former vice president and “attack man” for President Richard Nixon.

It was Nixon who made a point of appealing to the “great silent majority” of Americans. Nixon gave a nationally televised address in November 1969, seeking support for his Vietnam War policy against the backdrop of growing antiwar sentiment.

But it was Agnew who took to the road with speeches mocking the elite media that were critical of Nixon. He called them “nattering nabobs of negativism.” In words worthy of a Fox News versus Jon Stewart battle—and increasingly the United States Congress—Agnew proclaimed the uses of “positive polarization.”

Agnew still resonates

What’s meaningful to me—and appreciated by my 20-year-old college students—is how much the attacks by Agnew continue to resonate with the tone of resentment and anxiety that shapes political debate today. It is in this context that seeing Donald Trump atop the early Republican polls is both surprising and not.

Trump is certainly a spectacle (some say “clown”). He may be a force who crashes and burns early in this contest, but for now he is arguably speaking to some enduring sentiment among part of the electorate.

In a recent speech reminiscent of Nixon, Trump said, “The silent majority is back, and we’re going to take the country back.” In phrases worthy of Ronald Reagan, the one president held in high esteem by all Republican candidates, Trump has on his podium the motto to “make America great again.”

In journalist John Heilemann’s recent focus group discussing Trump, respondents articulated some of their reasons for supporting the 2015 Trump phenomenon:

“He speaks the truth.”

“He doesn’t care what people think.”

"He’s like one of us … besides the money issue.”

“I think we could be a proud America again.”

“To the American people it would be a presidency of hope.”

To such supporters, Trump is not a clown. He’s a folk hero—though an odd vessel for the articulation of resentment. In an era of economic anxiety and foreign policy frustration, it is predictable that immigrant bashing and Obama vilification are propelling the Trump candidacy.

But data, both demographic and attitudinal, suggest the opposite. America is becoming more diverse and Americans less wedded to some important “wedge issues” that have driven divisions in the American electorate for over 30 years. This change is happening across the breadth of American society, especially among the young.

In my new book, The Twilight of Social Conservatism: American Culture Wars in the Obama Era, I analyze why the shift in diversity and attitudes toward moral issues have made America such a different place now than when Nixon spoke and when Reagan ruled. The country has changed significantly even since 10 years ago, when Bush adviser Karl Rove predicted decades of conservative domination, in our “center-right country.”

There are three key reasons for this.

More accepting of gay rights

The first is that Americans have changed their attitudes on some of the key issues, such as gay rights and same-sex marriage, that fueled the culture war.

Same-sex marriage is now the law of the land in all 50 states. That change is paralleled by a steady growth in American public opinion supporting the legal reform. Not that long ago, opposition to same-sex marriage was a powerful “wedge issue.” It could be used to attract blue-collar but socially conservative voters to Republican Party candidates, including George W Bush in 2004. Now Republican strategists downplay discussion of it. Even Rush Limbaugh concedes acceptance of same-sex marriage is “inevitable.”

This shift is both attitudinal and demographic. As the millennial generation has come of voting age, its members’ progressive views on personal morality and the power of government to intervene have presaged a more liberalized American future. Fully 73 percent of those Americans born after 1981 support marriage equality. The emergence of the “ascendant majority” of millennials, unmarried women and voters of color that was key to the 2012 Obama reelection has replaced reliance on the “Reagan Democrats” who were interested in those wedge issues.

Americans less church-going

Secondly, while still much more institutionally religious than France, England or Germany, Americans have become more secular and less church-going.

The importance of religion—a key underpinning for the rise of the Moral Majority and the Christian Coalition—has dramatically changed. Americans are more decidedly secular (or “unaffiliated” or “unchurched”). Millennials over 18 lead them, at 35 percent unaffiliated. Meanwhile, Americans of faith have never been as dramatically conservative on such issues as coverage of religious conservatives might imply. For example, fully 60 percent of American Catholics now support marriage equality.

Latinos less conservative

Third, social conservatives—like the anti-marriage-equality group the National Organization for Marriage—cannot hope for the growing Latino presence in a diverse America to slow that progressive shift.

In 2012, the Pew Hispanic Center found that over 50 percent of Latinos supported same-sex marriage. Younger Latinos are a large part of the Latino population. They were even more pronounced in their views, in keeping with their millennial peers.

The culture war “wedge issues” that have been successful for over 30 years in politics are losing their edge. This “unwedging” is what characterizes America in 2015, especially among the millennial generation. It is hard to imagine a future in which these social conservative forces regain their salience and power.

One thing is clear: the 2012 call by Chairman of the Republican National Committee Reince Priebus and his committee for greater receptivity to the increasing ethnic diversity of America isn’t being heeded. Although the 2012 elections indicated the emergence of this potentially powerful “ascendant majority,” Thursday’s debate may ignore that reality and offer some Nixon-era nostalgia.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.