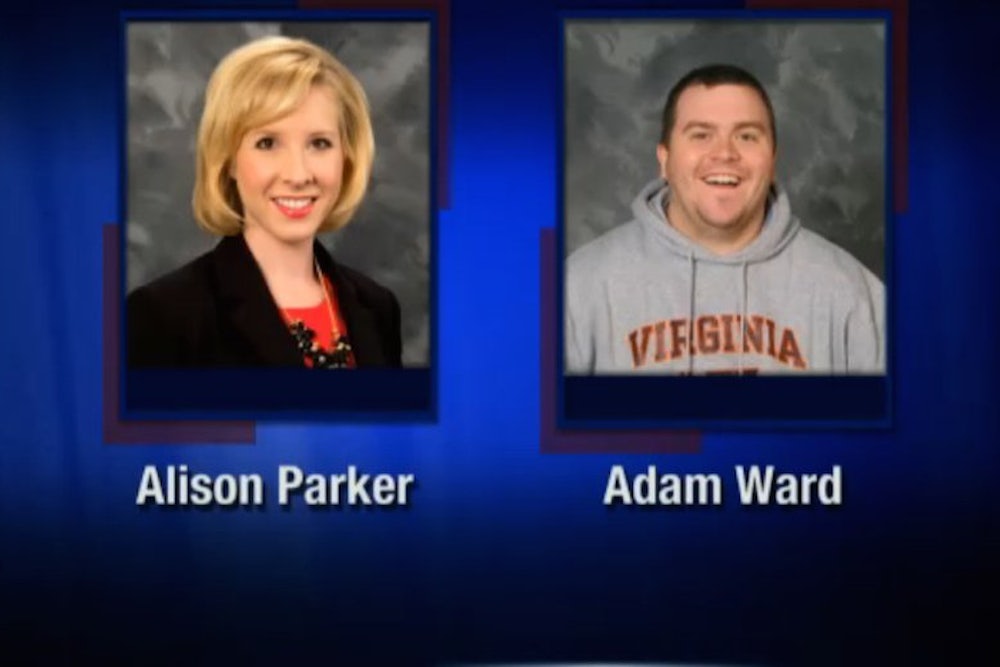

Vester Flanagan seems to have been proud of the fact that he recorded his murder of television journalists Alison Parker and Adam Ward in Virginia. “I filmed the shooting,” he tweeted earlier today, then posted two videos as proof. Aside from Flanagan’s own recording, the killings took place during a live broadcast. Since the videos of Parker and Ward being shot exist, the event is now not just a crime but also a story about the rules of media coverage. Should news outlets show the videos? Should news consumers seek out the videos? Or should we respect the victims by refusing to be voyeurs in their murder? These are questions all media outlets struggle with. To wit: CNN was initially showing the video, but changed its policy.

The taboo against circulating images of actual murders is a strong one, and for good reason: Showing and viewing such images is disrespectful of the dead and also painful to their loved ones. The moment of death, especially if it comes about in the terrifying form of murder, is deeply traumatic. To show images of someone dying without their permission is comparable to desecrating their remains, doing to the dead what they wouldn’t have wanted in life. And for survivors, to see images of the late beloved being killed is a reinforcement of the pain. This taboo is worth preserving even though there are exceptions that should be carved, such as when the narrative of the crime is disputed.

This is especially true in cases involving the police, like the killing of Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina, earlier this year. Since acts of alleged police brutality are often contested, and because there is a long history of police distorting facts to conceal culpability, it makes sense to air video evidence when it can help untangle the factual debate. This explains why loved ones and survivors often want these videos released and circulated. But in the case of Wednesday’s killings in Virginia, there is no factual dispute about what happened, so circulating the video is superfluous and cruel. It was Flanagan, not the crime’s survivors or victims’ loved ones, who wanted the images televised.

What’s true of acts of police violence also applies more broadly to war crimes, which are often denied or minimized. It makes sense to circulate images of the Holocaust, of the massacres in the former Yugoslavia, and of the tortures of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib in order to counter the tendency either to pretend these events didn’t happen or to whitewash the extent of the horror.

Finally, there is a political argument being made that showing the Virginia shooting is necessary to force America to confront the need for gun control.

Show the nation the crime scene photos of Sandy Hook. Plaster them on television wall to wall. Make America see what they tolerate. — kstreethipster

The problem with this argument is that while videos can help clarify factual issues of what happened, they never have clear political meaning. We watch such videos in the context of our political views. An NRA supporter could watch a video of the Virginia shooting and conclude that TV journalists need to be armed. And the fear of violent crime, which could be heightened by such videos, is as likely to inspire people to buy a gun than to support gun control.

Could showing the Virginia video help de-glamorize guns? Perhaps, but it could just as easily make those enthralled by gun culture put even more faith in weapons (the video filmed by Flanagan, with his handgun in the foreground, bears an eerie resemblance to first-person-shooter video games). The unlikely possibility that showing the video could promote gun control is no reason to make an exception to the taboo against showing scenes of real murders.

Of course, in the internet age, it’s impossible to fully banish such images. They will always find a home in sites like Reddit. But we can at least prevent them from circulating more widely on mainstream media, to minimize the damage done and especially to make sure survivors don’t have to see these images unless they want to.