For 80 years, the Heisman Trophy has been awarded annually to the college football player “whose performance best exhibits the pursuit of excellence with integrity.” Athletes from the University of Southern California, my alma mater, have won six: the tailbacks Mike Garrett, Charles White, and Marcus Allen; quarterbacks Carson Palmer and Matt Leinart; and O.J. Simpson, who defies mere positional categorization. Reggie Bush won the Heisman in 2005 but returned it several years later, when evidence surfaced that he and his family had accepted “improper benefits,” an NCAA term for money.

USC displays its Heismans in Heritage Hall, a 70,000-square-foot, on-campus complex, along with commemorations of the school’s 422 Olympic athletes and 123 national team championships, its heavier-weight financial donors, a few coaches, the best members of its woebegone basketball squads, and Marion Morrison, a.k.a. John Wayne, who played two seasons of football for the Trojans in 1925 and 1926.

Heritage Hall is also home to some of the infrastructure and amenities directed at the athletes: offices and meeting rooms, a two-story lobby and museum space known as the Hall of Champions, a “spa-like female athlete lounge featuring a kitchenette” (to borrow language from the DLR Group, the firm that oversaw a recent renovation), a $3 million sports-themed dining hall, a golf simulation lab, a workout room for the rowing team, a commercial laundry, a fully equipped television studio and editing suite, and other facilities. In its day-spa-meets-tech-campus-meets-pro-franchise grandeur, Heritage Hall serves as a two-pronged collegiate symbol: of the wider university’s formidable success, and of the materialist extremes that sport can achieve. Money and privilege practically ooze from the wall joints. It is on the campus but not necessarily of it.

In 2002, as a student in USC’s Master of Professional Writing program (not making that name up), I took a part-time job with Student-Athlete Academic Services (SAAS), an athletic department adjunct “committed to the growth of the total student athlete.” My job was to shepherd the athletes through the mind-numbing exigencies of Composition 101 and 102; our sessions were conducted in the basement level of Heritage Hall. (Today, most of this work takes place in a newer, even fancier building, the John McKay Center, named after a head football coach from one of the Trojans’ halcyon championship-winning eras.)

During my time with SAAS, I encountered a wide range of athletic archetypes: foreign-born tennis players struggling with English grammar; SoCal water polo dudes who excelled at swimming and skateboarding but not essays; a smattering of cheerfully inarticulate volleyball and baseball players and swimmers; and of course, the breadwinners and rainmakers: the football players.

Let us assume to be already in evidence the standard disclaimers about good and bad apples, smart and dumb, the motivated and the apathetic. With very few exceptions, I liked the athletes. They were unfailingly polite and appreciative, mildly apologetic when they didn’t do their work, and, overall, behaved as well as one can expect of exceptionally fit and good-looking young men and women enrolled at a fair-weather school not too far from the beach. In the main, however, they also struck me as unprepared for college-level work. What’s more, and again in general, the football players appeared the least troubled by this fact, and the least willing to rectify it.

These were not, I should point out, stupid young men. Football at this level presents highly complex strategic and tactical challenges. Dull minds, even ones blessed with superb athletic ability, will struggle. But practically all of the dozens of football players with whom I interacted resented their schoolwork, or to be specific, the requirement of it. They viewed it as a particularly onerous element of the raw deal that was playing collegiate-level professional sports for free. Without quite saying it, they viewed amateurism as a farce, a predatory bargain struck long before any of them had nailed their first slow-moving quarterback. They could live with the exploitation, it seemed, but certain things fell beneath their dignity, compulsory study being one of them.

The billion-dollar business ventures currently referred to as College Football and College Basketball have come under increased scrutiny of late, by a variety of actors, judicial, administrative, journalistic, and otherwise. The games and their related by-products—ESPN, video games, tight-fitting workout clothes, electrolyte-supplementing beverages—constitute a system of human resource extraction, one in which already wealthy universities derive enormous benefit from young men who don’t share in the riches they create. That the players are owed compensation for their part in these business concerns is today, I believe, considered the ethical norm by the majority of reporters, academics, and sports professionals—basically everyone but the NCAA—having supplanted the earlier prevailing belief in the nebulous virtues of amateurism.

“In economics, we are not allowed to use the word ‘exploitation.’ That’s for the sociologists. But if we were, [revenue-generating sports] would be a good place for it,” said Charles Clotfelter, a Duke professor and author of Big-Time Sports in American Universities. “If you work for the NCAA these days, you have to keep a straight face to say a lot of things.”

College athletics has, since its inception, been rife with academic indiscretions large and small. Among the latest, although not necessarily the worst, to be documented occurred at the University of North Carolina. In October 2014, an investigation conducted by an independent law firm found that for 18 years, more than 1,000 members of the men’s football and basketball teams had benefited from what was dubbed a “shadow curriculum.” Athletes, the investigators reported, were allowed—encouraged—to register for “paper classes” that involved “no interaction with a faculty member, required no class attendance or course work other than a single paper, and resulted in consistently high grades.” These athletes, the investigators noted, had been steered toward these courses by counselors from UNC’s Academic Support Program for Student Athletes, Chapel Hill’s counterpart to SAAS.

In the courts, O’Bannon v. NCAA, a class-action suit named after former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon, seeks compensation for players for the use of their likenesses in video games. A little more than a year ago, the judge in the suit ruled in favor of the players; the NCAA has appealed, but in response, the video-game company Electronic Arts, a co-defendant in the suit, has already discontinued its NCAA series of college football video games. A single case, perhaps, but it demonstrates the instability of the status quo and the shift in thinking with regard to collegiate-athlete compensation, which now seems appropriate, and more importantly, inevitable—the only right-minded way forward.

Embedded in this idea is the conviction that the inequity of withholding money from players is the primary structural problem of the collegiate sporting landscape. Make the athletes whole and the academic chicanery, the ribald recruiting competition, and the reign of the unaccountable coach-king with his lucrative shoe contracts and loudspeaker voice will vanish. The subjugation of the player, in this thinking, is the solitary sin of college sports.

I disagree. Division I athletes are being cheated of their just due by the present system, and they would undoubtedly be aided by the diversion of money their way. But the transfer of cash from the NCAA and the universities to the players would not address the basic problems of big-time college athletics. Why would it? What makes us believe that the creation of an explicitly professional class of student athletes (as opposed to today’s implicit class) would change anything? How would payments to the players mitigate the excesses of Heritage Hall or any of the other walled citadels of sport hogging valuable real estate on our campuses?

Taylor Branch, in “The Shame of College Sports,” his 2011 evisceration of the NCAA published in The Atlantic, writes, “The tragedy at the heart of college sports is not that some college athletes are getting paid, but that more of them are not.” But is it? To me, the tragedy at the heart of college sports is college sports. Paying the players would only ensure the continuation of athletic programs as currently constructed. Everything would remain as it is, with the freakishly lucrative enterprises that are Division I college football and basketball nestled awkwardly within our higher education system. Payment would, in fact, give the system needed space to grow, protect it with a thin veneer of legitimacy, and free everyone from the constraints that have lately burdened the good time of college athletics.

The NCAA is a cartel. Its operating model—as Lawrence Kahn describes in his aptly titled 2007 Journal of Economic Perspectives article, “Markets: Cartel Behavior and Amateurism in College Sports”—is based on limiting pay to athletes and forcing them to maintain their amateur status. The term “cartel” is a loaded one, of course, but its connotations suggest the limits of what paying the players could conceivably do.

I talked on occasion with athletes at SAAS about the workings of the cartel that drew profit from their play. These conversations inevitably turned to whether or not the athletes should be paid. One instance stands out: A group of young men from the football team had been consigned to Heritage Hall for an afternoon study session, their attendance, I believe, some sort of punishment for a missed class or an act of defiance toward their coaches. Instead of reading, they engaged in a lively chat about the ethics of not paying the players in what we were calling the “money sports.” The players did the work, they said, risked body and brain, so that USC might reap glory and heaping piles of loot from their labor. The loyalists in the seats chanted the names of star players, not those of their well-compensated coaches. The ludicrous centurion on his white horse mascot, the USC Song Girls, the ticket-buying partisans in cardinal and gold: They honored the players and only the players. Yet the players were paid only in acclaim, currency of some value in our society, but not of the sort that does much for a car payment.

The animating myth of the pay system is that big-time college sports are good for colleges, a belief best embodied by “The Flutie Factor.” In 1984, Doug Flutie, a Boston College quarterback, threw a last-second touchdown pass for a victory over Miami. A surge in applications the following year was widely attributed to him and also used to correlate athletic triumph and institutional prestige.

However, a 2013 report by the Delta Cost Project, a Washington, D.C., think tank, found that The Flutie Factor was “often cited but largely exaggerated” and called the impact of athletic success “typically quite modest.” Sports can improve a school—but so can a new building, better professors, or increased diversity.

Elite college-level athletics in the revenue-generating sports are among the very few sectors of working society that diverge from the American idea that labor yields pay. (And I write this as someone who got his start in magazine publishing via an unpaid internship.) Here, instead, cash takes another form, via a sort of ivory-tower alchemy. No longer offered as mere legal tender, compensation is transformed, via education, into a vehicle for the athlete’s “social betterment”—college is good for you, socially and personally, better even than money, or so goes the argument. That such fiscal chemistry occurs in pursuits dominated by African American men from low-income families should neither surprise nor please anyone. The NCAA and its member schools like to equate education with improvement, and I’m not about to argue the connection between the two—but it’s also a convenient justification for unpaid work.

In a paper published on the web site College Athletics Clips, Towson University professor Howard Nixon, author of The Athletic Trap: How College Sports Corrupted the Academy, writes:

In big-time college sports today, critics often attribute an assortment of problems to commercialism, including a financial arms race with no end in sight, academic misconduct that makes a mockery of the idea of the student athlete, and various other breaches of academic and athletic integrity that raise serious questions about the purposes of ostensible higher education institutions.

I see no reason to believe that the commercialism and the pedagogical mockery would subside if the players were paid. You could, I suppose, sidestep the entire issue by dropping the requirement that the athletes go to school. Given the option, many football and basketball players might, of their own accord, pursue a college degree, using the proceeds of their athletic labor to pay for it. Others would not. Either way, if the goal is to curb the scholarly scofflaw-ism—the commercialism still isn’t going anywhere—logic suggests that the players be allowed to choose to study or no. Of course, having well-paid college athletes opt into or out of the classroom may be good for them, and fair, but it can hardly be said to be for the benefit of the wider college population, the educational system, or the rest of society. The best that could be said for this approach would be that it would eliminate the hypocrisy of fake student athletes of the kind periodically uncovered by reporters and whistle-blowers and bemoaned as a scandal.

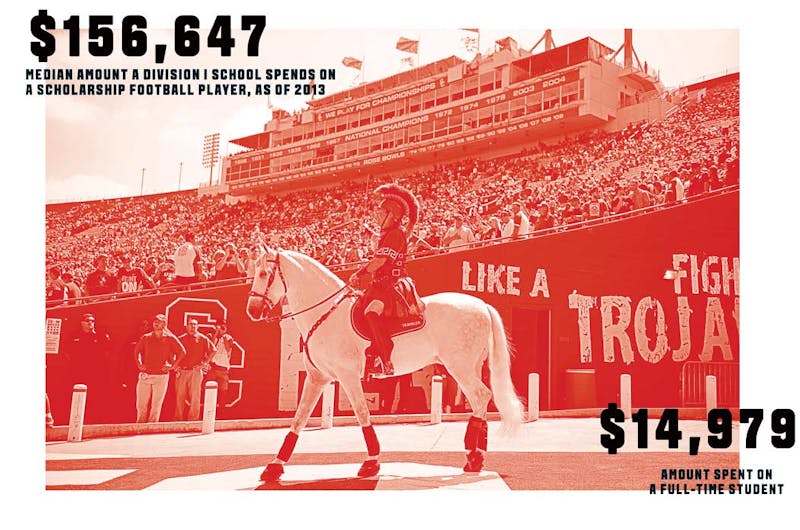

What shape might (and must) a pay system take? What impact would it have on this unsavory business? Certainly some of those employees and participants would gain: Earning money for one’s labor is always better than not. But the overall ramifications might be less positive than compassionate folks like Taylor Branch believe. An open market at the college level would, in the abstract, seem the most equitable approach: Give supply and demand free rein to deliver its judgments and all will be well. Schools could pay individual players based on the share of revenue derived from their talents relative to other players. The payments might vary according to the size and scope of the local sports market, plus the specific deal each young man (and there is little reason to think that the gender inequities in professional sports would not be replicated) is able to swing. But in general, each year’s Heisman Trophy contender and charismatic gridiron swell would be assessed and paid his worth. The current faux-amateur system, of course, diverts the better part of this player’s money in a multiplicity of directions. The coaches and athletic directors get their taste, as do various athletic department functionaries and the support staff (including SAAS folks like me); and we mustn’t forget the worthy dependents in the non-revenue (which include women’s) sports.

But the market-based approach, when examined closely, is a muddle. By what method will the schools determine the value of an individual player? And an unsettling corollary: What obligations do they have to the players who, put bluntly, aren’t worth all that much?

Even at the elite level, much of the athletic talent is essentially fungible. Compare, for example, USC with a nearby school like San Diego State University. Both institutions recruit, at least in part, from a similar pool of players. USC is a perennial football power with eleven national championships. SDSU is a fine school that plays some serious football, but it is, with apologies, a lesser force in the athletic firmament. The disparities in achievement between the two programs, however, cannot be attributed to, say, a starting Trojan linebacker without NFL potential on one squad and a starting Aztec linebacker without NFL potential on the other. Each is a high-level athlete, but both could effectively be swapped without impacting the outcomes for either team. Even in football, and at the risk of cliché, championships are won by the superstars. And if you are entirely replaceable, can you really be said to be contributing to the financial success of the program? In short, are you worth anything?

The best players on the best teams hold undeniable financial value because they are rare. More than 30,000 men play NCAA Division I football and basketball each year. A little more than 300 are drafted into the NFL and NBA. There are very few Marcus Mariotas, the University of Oregon quarterback who won last year’s Heisman, walking the planet. Gifted but unheralded teammates like Andre Yruretagoyena, an offensive lineman, are far easier to locate and develop. Or another, more personal example: Among the athletes I spoke with about pay while at USC was a highly recruited freshman safety who had earned, among other notices, Super Prep All-Dixie honors as a high school senior in Florida. Unfortunately, he didn’t quite prove out at the collegiate level: He was gone from the football team after his sophomore year. In a supply-and-demand system, the value of a premium player rises, while that of the borderline one plummets. Not to zero, likely—don’t sweat it, Andre—but not necessarily much above it. No one is suggesting that a Division I player would be asked to pay to play. Even the most marginal team member would still likely merit a scholarship. But the basic point remains: The current system deprives the best players of significant money, not the lesser ones. Let’s be clear about who’s really being exploited.

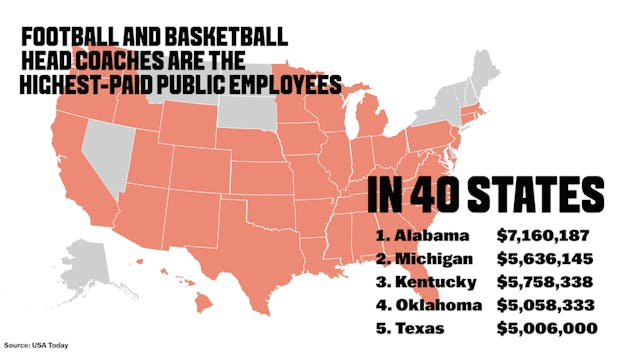

Not every college would be able to afford to compete on the open market. Think USC versus sdsu again. The Trojans are a national brand as well as a national power; an expensive private school, with wealthy alumni and boosters, and an iconic sports institution that people around the country support by buying T-shirts, caps, foam fingers, and tiny replica football helmets. The Aztecs possess few of these attributes and wouldn’t necessarily have the money to stay in the big-time game, although they might opt to do so even without it-—a 2013 analysis by USA Today found that only 23 of 228 public school Division I athletic departments ran in the black. (Private schools don’t have to disclose their finances.) Duke’s Clotfelter dismissed these figures as arbitrary accounting practices. Basically, the schools can choose to appear to lose money if the profit-making football teams are expected to pay for the money-losing tennis squads. “It’s a bogus thing to even be talking about losing money,” he said. True or no, it doesn’t prevent 16 of those 23 departments from taking financial subsidies from their schools, often in the form of student fees.

Some schools might decide not to try. “You’d have teams that fail and go under,” said Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College. A smaller, wealthier core, likely composed of the teams in the so-called Power Five conferences (the ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12, and SEC), would emerge. But even within those conferences, some schools might decide competing wasn’t worth it, and they’d move down to Division II.

An early version of this fiscal sorting may already have begun. An NCAA vote in August 2014 afforded the Power Five increased autonomy over the rules governing the treatment of players. For example, Alabama, which plays in the SEC, can now offer its athletes better health insurance and scholarships than, say, the College of Charleston, which competes in the Colonial Athletic Association. Last December, in a harbinger of what might happen in an open market, the University of Alabama-Birmingham, which plays in Conference USA, a “mid-major” in the current parlance, announced the termination of its football program, citing insufficient financial resources. “As we look at the evolving landscape of NCAA football, we see expenses only continuing to increase,” UAB president Ray Watts said. “Football is simply not sustainable.” Six months later, UAB decided to resurrect the football program, possibly as soon as the 2017 season. In an interview in June, Watts said the school’s students, alumni, and the city of Birmingham itself had “stepped up,” with $17.2 million to cover the team’s operational deficit. The overall dynamic for the smaller schools remains ominous: An open market system would sustain premium teams that have the ability to compete for premium players on the basis of how much they could pay them. The rest could be forced out of existence altogether.

One unavoidable by-product of the reduction in programs would be a corresponding drop-off in the number of athletic scholarships. “If you introduce an open market, or a quasi-open market,” Zimbalist said, “the coaches would no longer have 85 scholarships.” He estimated that the number might shrink to 45, or about the same as an NFL roster. “If you have to pay, then you become more frugal.” Consider the ramifications: This new, purportedly more just system would provide for the professional-quality players at the expense of the larger pool of merely elite ones. Remember that the people swept away by this capitalist tide would largely be young men from low-income backgrounds, many of whom would not qualify to attend their schools on academic merit. It is an odd remedy for exploitation that takes away access to education for significant numbers of the exploited.

The intricacies of pay systems, of who would be paid what and why, merit further deliberation. The byzantine work-arounds needed to square everything with Title IX, the admirable law that requires similar provisions for male and female athletes, would have to be reckoned with. As would full and fair compensation for revenue indirectly tied to on-field performance, as with the O’Bannon case. The ruling for the plaintiffs recommended that at least $5,000 per player, per year of eligibility, be set aside to compensate the players for their use as video-game avatars. The money would be kept in a trust until each player completed his eligibility. Not exactly big money, but it really should be if we’re striving for equity of treatment.

One avenue through which to construct a workable pay system would be via the union constructs found at the professional level: minimum salaries, collective bargaining, salary caps, drafts, and so forth. In April 2014, a regional director for the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which oversees unionization efforts for the federal government, allowed the football players at Northwestern University to hold a union vote. More than a year later, the NLRB’s national body unanimously declined to grant the players the right to unionize, determining, at least for now, that the players are students, not employees. (The NLRB noted that Northwestern was a single school engaged in such an effort and left room to change its ruling if a broader movement toward unionization arose.) “The problem from the athlete’s standpoint is their legal definition as amateur athletes and not employees,” Towson University’s Howard Nixon said. “You open that door, and then you get the possibility of all different forms of compensation. That scares the NCAA. They won’t even use the word ‘compensation.’”

Employees unionize; students do not. This returns us to the idea of what restrictions can be placed on the autonomy that working people possess over their earnings. One can reasonably argue for encumbrances on the activities of student athletes. They are trainees, essentially, in need of guidance. The same can hardly be said for university employees. In a professional collegiate football system, it would be hard to justify forcing the laborers to buy an education. Minimum academic standards for admission would no longer make sense, either: These workers aren’t being hired for how they did in high school algebra. Time permitting, many players would avail themselves of the opportunity to go to school; that’s about as far as the logic can stretch.

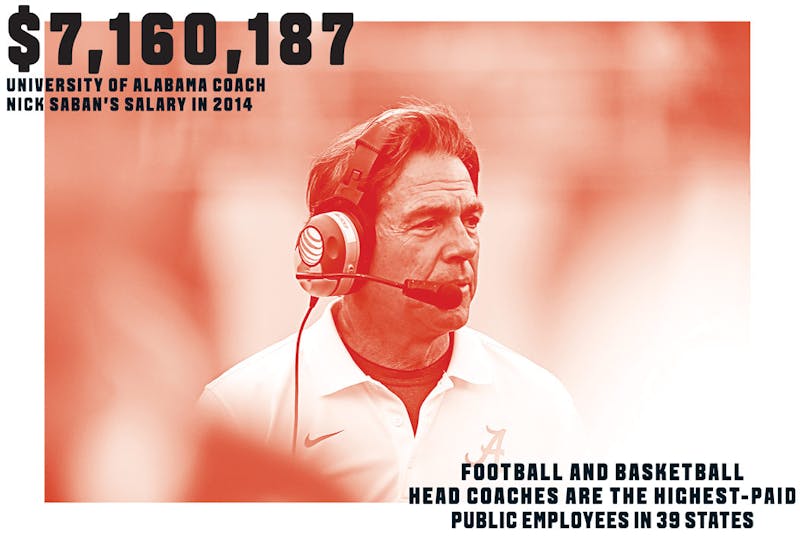

One happy consequence of a pay system: The coaches would in all likelihood make less money. “When I was a kid, I went to the bank to set up an account, and they gave me a free toaster,” said Andy Schwarz, an economist and antitrust expert who has testified to Congress in favor of paying college football and basketball players. “They competed on perks, and the toaster was the shiny lure.” Coaches are among the most important “shiny lures” in today’s college sports, he said, and they are compensated in line with their luster. Nick Saban, football’s highest-paid head coach, earned $7,160,187 in 2014; Mike Krzyzewski, the Duke men’s basketball coach, took home $9,682,032. In many cases, the coaches are their state’s highest-paid public employees. Rudimentary economics suggest that in a pay system this should change: The supply-and-demand response would shift away from the coaches and toward the players. “The moment the banks could compete on interest rates, they stopped offering toasters,” Schwarz added. “It’s not that coaches won’t matter. But they’ll be worth less.” This would be a worthy outcome, but an ethically weak prescription for addressing the NCAA’s cartel behavior.

The largest potential impact of a market system, one hopes, would be the demise of the NCAA as a governing body of a Fortune 500-like corporation. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, in a landmark 1984 decision that broke the NCAA’s monopoly on sports broadcasts and paved the way for today’s billion-dollar conference-television contracts, remarked that “The NCAA plays a critical role in the maintenance of a revered tradition of amateurism in college sports.” If the players join the cartel, however, that revered tradition ceases to exist, and the body that primarily serves to separate the athletes from their money becomes redundant. That’s what agents are for.

Ultimately, none of these permutations are prohibitive. Other proposals could be weighed, wrinkle upon wrinkle, variants both elementary (pay players based on minutes played) and ornate (spin the largest programs off as private, university-branded corporations). A pay system could be created. There are a lot of smart people in this country. I have confidence that someone could devise a method for spreading around football and basketball money in a form agreeable, if not to all, then at least to most. It could be unionized, if that’s what the players wanted, with all the good and frustrating things that issue from that. (Rose Bowl strike!) The new system could be lucrative or modest, as the interested parties see fit. The obstacles could be overcome, the details worked out, the rough edges negotiated smooth. But the question of whether we should remains unanswered.

Sports at the college level, particularly the money sports, are about much more than the games: They represent a form of social leveling and an avenue for social justice. Football and basketball afford access to higher education to groups of gifted young men who might not receive it otherwise. But if the goal is to make social redress—and ours is a society most definitely in need of correction—why do we believe that its best expression is via the athletes? When the players I knew at USC argued in favor of compensation, I would often think of their high school girlfriends, or the valedictorian at their schools, the kids who wanted to be actors or engineers, any of the meritorious others who do not get free rides to college.

Given what we know about college sports, and college athletes, couldn’t it be argued that other people are, in fact, more deserving of a subsidized education? If we want to make our society and our schools better, then perhaps we should do just that. The effort and attention devoted to finding the best student athletes in low-income communities could be put instead to finding the best students in those same places. Paying the players would move the money around, place more of it in deserving pockets, slice up the pie in ways that would more fairly satisfy all appetites. But everyone keeps eating.

The largest myth surrounding college sports may be its inevitability. Revenue-generating college athletics make a lot of money. It can be argued that they exist, for the most part, not so much for sport but as machines calibrated to generate revenue. The efficiency of the machinery, the fact that it works well, and that we delight in its output, serves for many people as a philosophical reason to keep the line moving. Money, once made, cannot be unmade, after all; college sports are lucrative and therefore immutable. This right-wing, job-creation tautology strikes me as the best argument of all for disassembling the NCAA’s too-big-to-fail structures. Instead we use it as an opportunity to push seat licenses onto a sports-mad public.

It’s possible, however, to imagine a humbler, genuinely amateur version of college sports. Not the fictional, faux-amateur one found in today’s NCAA—I carry no water for the status quo. The current system is abhorrent, and in advocating against the payment of players, I am not suggesting that the NCAA, the schools, or the coaches continue to keep the money generated under an ethically bankrupt structure. But I also believe in the educational missions that our schools and athletics programs never seem to operate within.

I would like to find a way to bring a genuine student athlete onto our campuses. Yet to do that, the primary obstacle to his and her existence—the enormity of the money—must be addressed. No more TV contracts and cable deals, endorsement revenue and ticket income, video games and sweat suits. In this scenario, swank athletic facilities like Heritage Hall would fade into irrelevance, but be left standing, their sagging hulks a blight on the landscape of our campuses, like the Soviet-constructed, Brutalist monoliths dotting the fallow exurbs of second-rate Russian cities.

So be it. Money is a blight on college sports. We must remove it from the equation and leave the good things: sports and schools.