On a recent morning in the Copenhagen suburb of Gentofte, Marie Louise Esbech and her husband, Bo, hosted a gathering of relatives and friends to celebrate their son’s first birthday. For Marie Louise, a 32-year-old chemical engineer, the occasion also marked her first full month back at work after almost eleven months of maternity leave—during which she received her full salary. “I’m very grateful for my maternity leave option,” she said with a smile.

Denmark, along with its Nordic neighbors, is well known for its generous paid family leave policies. The government promises parents up to 52 weeks of paid leave around the birth or adoption of a child, 32 of which can be split between parents.1 But the benefit, both in theory and practice, is not as egalitarian as it seems. Danish fathers are assured only two of the 52 weeks of paid leave, and on average only take 7.2 percent of the shareable leave. With more than half the paid leave available to them, why do Danish fathers take so little of it?

One reason is that Danish men, on average, earn 16.4 percent more than women, which means many families are better off financially if the father continues working while the mother takes most of the leave. As a consequence, fathers like Bo, a 33-year-old engineer, must decide if time with their newborn is worth the lost income. Because he wanted to stay home without taking away from his wife’s fully paid leave time, Bo resolved to take three months of unpaid leave after negotiating with his employer. “From a financial point of view, I should have stayed at work,” he conceded. “That would have maximized our income.”

Denmark’s unequal distribution of parental leave also contributes to a highly gender-segregated labor market. Since women take most of the parental leave, private employers looking for full-time workers have a disincentive to hire young women who, if they become pregnant, will require a substitute worker.2 Thus, many Danish women opt to work in the public sector for its abundance of part-time jobs. A 2010 report by Denmark’s Ministry of Employment found that two-and-a-half times more women work part-time than men; family responsibilities was the top reason women gave for doing so. The result: Danish women comprise 68 percent of the public sector workforce but only 38 percent of the private sector.

The gender pay gap and segregated labor market have prompted calls to reform Denmark’s parental leave policies. In 2011, the government proposed a solution popular in the other Nordic countries: to earmark a portion of the total shared parental leave exclusively for fathers. The impassioned debate that ensued, and the ultimate fate of the “father’s quota,” should serve as a lesson to U.S. policymakers as the movement for paid family leave reaches critical mass: Get the law right the first time around, because there might not be a second chance.

Working women in Denmark rightly avail themselves of the generous benefits guaranteed to them by the state. Ninety-nine percent of mothers take the maternity leave earmarked for them, and on average mothers take 28 of the 32 shareable weeks, according to the International Network on Leave Policies and Research. Once the leave time has been exhausted, Denmark’s child care system enables women to resume working. Seventy-eight percent of Danish children between the age of 1 and 2—and 94 percent of children between the age of 3 and 5—are enrolled in heavily subsidized child care or municipal family day care facilities.

These policies boost women’s participation in the labor market: The employment rate of mothers with children less than six years old in Denmark is 86 percent, according to Mette Verner, an economics professor at Aarhus University. By comparison, only 63.9 percent of mothers with children under six work in the United States. “To the extent that we want to have family-friendly policies that make it possible for women to be in the labor market, we have succeeded, no doubt,” Verner said.

Women’s high employment rate reinforces a virtuous cycle which sustains the Danes’ cherished welfare state. The system is primarily financed by high income taxes—38.4 percent for the average wage-earner—and a 25 percent sales tax. These high taxes then fund the benefits and services, such as parental leave and public child care, that allow people to stay connected to the labor market even after the birth of a child. As a result, Denmark and other countries with similarly high taxes and generous welfare spending have some of the world’s highest employment rates.

But as Verner noted, women who take most of the parental leave are also subject to a figurative “child penalty.” For each child they have, women miss out on pay raises, pension contributions and opportunities to advance their careers—all of which contribute to Denmark’s long-standing gender pay gap.

“If we compare the inequality, men aged between 30 and 40, their wages go like this,” Verner said, pointing up. “And that’s mainly driven by changing jobs. So it’s not unusual to have three or four or five jobs within these ten years. So that’s good for men, but the point is that women don’t really have the same opportunity if they have two or three kids in the same time period. Because actually, what a lot of women want in that period is one good stable employer.”

That is what Marie Louise Esbech wants.

“I have had quite a lot of offers where they give much more money every month, but then the maternity leave isn’t as generous,” she said. “And now I’m thinking I want a second kid while I’m at [my current job], and then I can go somewhere else.”

Lise Johansen, an advisor on gender equality and family policies at the Danish Confederation of Trade Unions, which represents about one million mostly blue collar workers, said paid leave “is very, very central” to gender equality.

“What happens in Denmark is these paths of women and men separate once they have kids,” she said. “And then you get this traditional—I wouldn’t say as traditional as the U.S.—but we tend to find these very traditional boxes when we become parents.”

Although Denmark’s parental leave policies strengthen men’s position in the labor market, fathers are the ones pushing for more equal leave. “The fathers we represent are the most positive in terms of getting these rights more formally,” said Johansen. “If we ask them, nine out of 10 would love to take a long leave.”

Why, then, do fathers take so little of the shareable leave? Johansen pointed to opposition from mothers and employers.

“Mothers think it’s a bad idea because they find that that’s her privilege to stay home for the year,” she said. “And the employers think it’s a really bad idea because they have these very small companies of carpenters or whatever, and if he’s away for a month, how would they cover that?”

Jesper Lohse, head of the Danish Fathers Association, said that the way the parental leave legislation is written ensures that, in the event of a disagreement between the parents about how to split the leave, all of the shareable leave will go to the mother.

“What we see is that some of the men who would really like to go on parental leave are not given the chance,” he said. “It is the family economy that decides who is going to take parental leave, and it’s also if a mother or an employer is stating, ‘We don’t want you to take parental leave,’ then the father will not have that opportunity.”

Fathers who want to take more leave also face a “stigma” in the workplace, according to Johansen. “We represent the blue collar working men, and they happen to have the worst rights—they work in the private sector and you often see at the small private workplaces where they are working that … their colleagues think it’s a bad idea for the man to be home with his baby—I mean it’s still a cultural barrier,” she said.

Recent surveys support Johansen’s claims. Among Danish men who do not take any of the shareable parental leave, 88 percent are employed in the private sector. Another poll found that more than 50 percent of fathers who took less than three months of parental leave reported that “if my employer had clearly indicated that my job situation would not be negatively affected” and “if my work place had a tradition for male employees taking leave,” then they may have taken a longer leave.

“So fathers do have a problem, especially fathers with private employers,” said Anette Borchorst, a political science professor at Aalborg University. “The family structure is changing—the fathers are becoming more and more fathers—but the political regulation doesn’t follow these changes.”

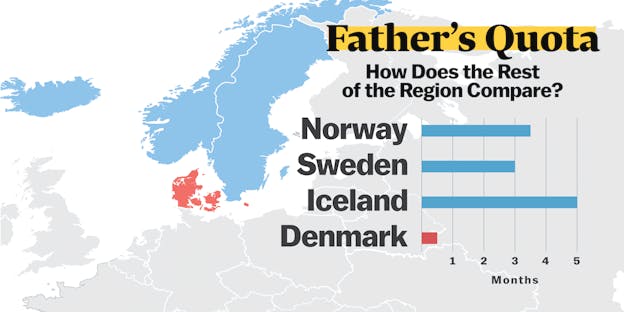

The unequal effects of Denmark’s parental leave policies have prompted researchers to look to neighboring nations with similarly generous policies but higher rates of leave take-up among fathers. Whereas Danish fathers use only 7.2 percent of the shareable leave, fathers take 18 percent in Norway, 24 percent in Sweden and 33 percent in Iceland.3

Tine Rostgaard, professor in comparative welfare studies at Aalborg University, attributed these differences to a policy instrument called the father’s quota: an individual, non-transferable, use-it-or-lose-it portion of parental leave reserved for the father to be taken separately from the mother. Although Denmark guarantees the father two weeks of paternity leave, these weeks must be taken with the mother shortly after the child’s birth and therefore do not constitute a true father’s quota. By comparison, Norway has a father’s quota of 14 weeks, while Sweden’s will increase from 60 days to three months in 2016. Iceland’s father’s quota will jump from 13 weeks to five months also in 2016.

“Looking at other Nordic countries when they have introduced the father’s quota it is a very, very effective policy instrument,” Rostgaard said. For example, in the year after Norway increased its father’s quota in 2012 from 10 to 12 weeks, 21 percent of fathers took exactly 12 weeks of leave, compared with only 0.6 percent the year before the extension. Similar effects have been measured in Sweden and Germany.

Such quotas not only benefit fathers; they also level the playing field for mothers in the labor market and at home. “[T]here’s other research that shows there’s a long-term effect in terms of women’s wages, in terms of women’s career opportunities and their pension opportunities and also in terms of how mothers and fathers share housework both during parental leave but certainly also following parental leave,” Rostgaard said.

Marianne Bruun, a senior adviser on gender equality for the United Federation of Danish Workers, Denmark’s largest union, said her organization supports a father’s quota as a way to address gender discrimination in the hiring process. “The moment the father would be absent from the labor market to the same extent as her, he would be considered ‘risky business’ to the employer to the same extent as she is,” she said.

Although there is no nationally legislated father’s quota in Denmark, some agreements between employers and unions include one. For instance, in 2008 Denmark’s large public sector earmarked six weeks of leave with full salary exclusively for fathers on top of the two weeks of paid paternity leave already guaranteed by law.

Nanna Kolze, a negotiator on working conditions for Local Government Denmark, the organization representing Denmark’s 98 municipal governments, said the father’s quota was introduced both because municipalities were trying to create attractive working conditions and unions were pushing for family-friendly arrangements. “We had a saying that we didn’t want to be a second labor market next to the private,” she said.

Lise Bardenfleth, a senior adviser at the Confederation of Danish Employers, which represents more than 28,000 private Danish companies, took a different stance: “We think that how you divide leave between the parents, that’s something the parents should agree on, not what the government thinks is the way to divide it.” She added that, in the companies she represents, “two-thirds of all employees are men. And if there’s a quota concerning fathers, there’s a lot more persons in our field who’ll be taken out of the workforce. So it’s a bigger problem for us.”

Johansen, who represents the trade unions in negotiations with Bardenfleth over parental leave policies, countered by noting that the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise endorses a father’s quota as a way to gain access to the better-educated female workforce. “I just find it so short-sighted that [the Confederation of Danish Employers] look at the problem right now,” Johansen said. “So if this one father in this small workplace should take leave, what should they do? Well what about 20 years from now when they’ve missed out on all the skilled women workers that could create more wealth for the society?”

“But of course we don’t agree on this point,” Bardenfleth responded.

This disagreement is representative of the broader rift over the father’s quota, one that Danish politicians hoped to resolve with new legislation. Given the strong backing for a quota from Danish fathers and the politically powerful unions, how hard could it be?

In 2011, Denmark’s Social Democratic Party won the country’s national elections on a platform that included a 12-week father’s quota. Despite their victory, the Social Democrats stalled on the proposal, which immediately became contentious. “Quotas just don’t go in Danish politics,” Johansen explained. “We have the same thing with women on boards. And that’s very specific Danish compared to Sweden and Norway and Iceland.”

Johansen attributed this to the framing of the issue: A number of public opinion polls simultaneously showed support for strengthening a father’s right to parental leave while also showing opposition to a father’s quota. Surveys conducted among her confederation’s union members found that women were most opposed to a father’s quota.

“The men we represent, who are younger than 50, they still support it,” she said. “Call it ‘quota,’ call it whatever, they know what this is about. But the women we represent, they are against it, and they are even more against when you say ‘quota.’ They become much more balanced when you say this is a matter of securing a father’s right to individual leave.”

Regardless of how the issue is framed, women’s opposition is understandable, said Borchorst, the political science professor. “It is interpreted as taking something from the mothers,” she said. “And the present government does not want to expand the leave further, so if they earmark something for the father it should be taken from the period that is shared, and everybody—mothers, fathers, employers, colleagues—they think about the shareable periods as mothers’ leave.”

“You can’t take something from somebody that they have been used to and that they take for granted today,” said Bruun from the United Federation of Danish Workers. “It’s very difficult to make this cutback.”

Thus, in 2013, the Social Democratic Party officially abandoned its proposal.

“We don’t know why the government abandoned their proposal,” said Kolze, the negotiator for Denmark’s municipalities, “but perhaps some within the government thought that this was not a question they could gain votes on.”

The lesson here, Borchorst said, is that Denmark should have implemented a father’s quota when the current parental leave period was introduced in 2002. No country should absorb that lesson more completely than the United States, the only developed nation that does not guarantee paid maternity leave.

Eighty percent of Americans think employers should be required to offer paid leave, overwhelming support that policymakers are finally responding to with a spate of proposals. At the national level, President Barack Obama in January signed a memorandum mandating that federal agencies advance new mothers and fathers six weeks of paid time off, and Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, the independent senator from Vermont, has backed a bill introduced by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand that would guarantee 12 weeks of “gender-neutral” paid family and medical leave. At the state level, California, New Jersey and Rhode Island currently offer paid parental leave, and 13 additional state legislatures have recently introduced or advanced similar bills.

The Gillibrand, California, New Jersey and Rhode Island bills all deserve credit for making the same benefit available to every person on an individualized basis. By replicating this design, states introducing or advancing their own parental leave bills would ensure that both parents have equal access to equal leave time to be taken either simultaneously or separately, and therefore would avoid a situation like Denmark’s. It would prevent disputes between parents about how to divide shareable leave. It could help overcome gender stereotypes, reducing the pressure from bosses and co-workers that discourages Danish men from taking leave that is not earmarked exclusively for them. And if momentum builds around an expansion of paid parental leave in the future, it would create an incentive for both women and men to advocate together for an extension, since both would benefit equally.

The female employment rate in America has been steadily declining for the last decade, and the gender pay gap is 18 percent. Guaranteeing generous, equal paid leave to mothers and fathers would go a long way toward rectifying those problems—but not all the way. Lawmakers need to get cracking on paid child care, too.

The state-provided leave benefit level is based on former earnings up to a ceiling of around $600 per week, although agreements between employers and unions often guarantee workers their full salary during some or all of their leave, as in Marie Louise Esbech’s case. When this occurs, the employer receives the worker’s benefit as a refund to help cover the cost.

A Danish trade union recently found that 17 percent of all women surveyed, including 25 percent of women aged 31-40, had been illegally asked about their plans to have children during a job interview.

Although Finland is also a Nordic country, its parental leave scheme is more complicated and recently underwent a significant change, making a side-by-side comparison with the other Nordic countries difficult.