Five years ago, the confluence of globalization, the internet, and the popularity of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love led to a spate of think pieces mourning the death of the great travel writing tradition. Graeme Wood complained in Foreign Policy that the ease of travel had somehow lessened the vitality of travel writing. “Inconveniences are disappearing,” he wrote. “The bad news for readers is that those inconveniences are the very stuff that concentrates the mind and transmutes narcissism into something approaching insight.” At The Daily Beast, Malcolm Jones lamented that the tradition was in decline because the “subject matter is literally running out,” as though great swathes of the earth were being swallowed up in catastrophic sinkholes.

What is taking the place of those traditional travel narratives like Gertrude Bell’s The Desert and the Sown and Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia, according to those who sounded the alarm, is a growing trend towards personal writing—the interior journey given as much import as the exterior in books like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, Mary Morris’ The River Queen, and, of course, Eat, Pray, Love. Wood complained that in the modern day “the writer goes overseas but brings back news about a tedious inner crisis, leaving undisturbed any insights about the places visited.” Jessa Crispin has called this “faux travel writing,” where “the focus of attention is the self, and the beautiful locale becomes the backdrop of the real action, which is the interior psychodrama.” Though critics have pinned this style to women—who, it is suggested, are more comfortable framing their travels as memoirs and are inherently more inward-looking—it can also be found in the lengthy first-person travel essays posted by travelers of both genders on websites like Roads and Kingdoms and Nowhere.

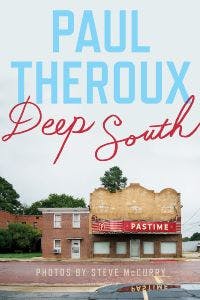

Paul Theroux, grand doyen of American travel writing, is determined to be a bulkhead against this excessive slippage towards interiority. His latest book, Deep South, offers an example of the thrills—and problems—of the traditional travel writing narrative. The story of four seasons of road trips around the American South, Deep South is not explicitly about how to write about travel. But over his long career Theroux has regularly enumerated clear rules on how best to travel —never in an airplane—and how to write about that travel—never in the present tense. He continues to follow these rules in Deep South, in which his observations on the way his travels have changed him take a backseat to his observations, criticisms, and celebrations of what he has seen. Still, there are times when more evidence of Theroux’s interior psychodrama would have been welcome. His confidence in his own insight occasionally leaves him blind.

The traditional travel narrative, of which Theroux is an acolyte, originated with the Victorians, who prized first contact with strange, possibly hostile new worlds. There had been travel writing before—Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus, and other explorers summarized their trips for readers and financiers at home—but the Victorians perfected the commercial art of the adventure plot. In 1853 Richard Burton disguised himself so as to be the first white man to visit Mecca, in 1878 Henry Stanley described his deadly expedition in central Africa in Through the Dark Continent, and in 1899 Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden” informed the world that it needed the European to travel, interpret and correct. The marvels and challenges of the world existed to reflect glory back on its conquerors.

By the 1970s, when Theroux himself emerged as one of many writers cataloguing world travel amidst globalization, travel writing began facing criticism from the academy. Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) castigated historic European travel writers for their representations of the Middle East. The genre was founded by men and women whose freedom to travel and write was inextricably linked to empire and capitalism. David Livingstone’s obsession with finding the source of African rivers was motivated by his desire to open the continent to Christianity and European commerce. Constance Sitwell’s Flowers and Elephants (1927) presented the British Raj in India as dreamy and romantic, a luxurious wonderland, and Gertrude Bell’s knowledge from her travels came in handy when she participated in Britain’s formation and administration of modern Iraq. These writings, though full of textured detail, never describe any essential shift in the author’s perspective or understanding. They pivot instead on moments of great external discovery: a waterfall, acceptance into a harem—anything exotic or a little bit dangerous.

Theroux’s writing often follows a similar trajectory of danger and discovery. He takes trains from London to Japan in The Great Railway Bazaar, paddles across atolls in The Happy Isles of Oceania, and returns to the railroad to travel from Cairo to Cape Town in Dark Star Safari. Oftentimes the worse the journey for Theroux, the better for the reader: his foot fungus in Oceania, his pain at having only bushmeat to eat on the way to Angola, and his perpetual disgust with cacophonous fellow tourists are the most delightful scenes to read.

But his books have never been so outwardly imperialist. What separates him from the haughty Victorians is that he reflects those criticisms equally towards those at home and abroad. He offers criticism of governments in China, Africa, and the South Pacific, but also knows that there are better ways of life and society than the American one. In Deep South, for example, Theroux repeatedly points out the hypocrisy of the amount of U.S. aid sent to African countries when there are counties in Arkansas and Mississippi with derelict houses and abysmal education rates, chastising the American tendency to make grand but empty gestures of generosity abroad while allowing the South to decay. A Victorian would never have admitted there were problems at home.

Although Theroux’s opinions are more palatable to our modern liberal tastes, he shares with his Victorian predecessors a disinterest in changing those opinions. Theroux is never softened by his journeys. Visiting may alter his views on a place, but rarely does it change his perception of the world at large. His authoritative tone is part of what makes him a compelling writer: Here is a man who knows what he is talking about, his writing says, and so the reader trusts both the veracity of the events he describes and his overarching analyses.

But in Deep South, Theroux could benefit from an infusion of contemplation. Although the majority of the book has all the hallmarks of a brilliant Therouxvian travel tale, a few misjudgments poke through and threaten his authority. It is not Theroux who has changed, but us: a white man writing what he thinks about a place as racially charged as the South is uncomfortable, and his tone comes off more as a crotchety old man with outdated views on race and gender rather than a keen observer qualified to write about the complexities of the South.

For example, in one scene Theroux is given a verbal dressing-down by a woman who explains white privilege to him. Theroux arrived late to their appointment without warning her, and is then surprised that the woman took offense:

“You arrived late and were in a position to notify me ahead of time. But chose not to, because you assumed I’d be available,”—I started to protest but she talked over me—“as I’m black.”

Theroux, pointedly, does not apologize. He does not consider his lateness to have been a problem, suspects that the woman “was not black at all,” and paints the woman as grotesque and ridiculous. Her voice is “shrill,” her face “scowling,” and her “wild corkscrew curls” give her “a gorgon-like aspect.” Theroux makes a show of writing down the words “white privilege” in his notebook, but then says “Hmm,” making it clear that he is only placating this crazy woman.

Theroux manages to see himself as the victim of this situation, then gets to go about the rest of his trip without really thinking about why the woman may have been so upset. He expects sympathy for the fact that she talked over him, when really his voice—as a white, male, best-selling author—will always be louder, as demonstrated by the fact that this scene is now immortalized purely through his perspective. Perhaps the woman was unpleasant, and perhaps it wasn’t the most egregious example of white privilege, but it’s the only mention of white privilege in the book at all. The incident could have been a turning point for Theroux, one where he was forced to examine the reasons behind his behavior, a natural segue to talk about some of the most pressing issues in the South. Instead, he paints it as an isolated, absurd incident, downplaying the current urgency of the national discussion around white privilege because he is confident that his personal beliefs preclude him from any racial imbalance.

There are other occasions of stinging word choice that could have been corrected with more self-consideration. Theroux notes that a man he meets is “a dot Indian with a caste mark on his forehead rather than a feather Indian” and calls George Zimmerman’s trial for killing Trayvon Martin “celebrated.” He describes the then-22-year-old Strom Thurmond’s sexual relationship with his 16-year-old black housemaid as seduction, writing that Thurmond “took her as his lover,” when in fact it was statutory rape. Theroux’s insistence on barreling forward without any real evaluation of his own perspective make parts of Deep South seem outdated from the moment of its publication.

Still, Deep South has plenty of the richly textured observations typical of Theroux’s best work. Minute interactions are strung together to reveal a vivid portrait of interconnectedness. Theroux’s vision of the South is prismatic, a place that is simultaneously mired in inescapable Civil War history and a window to a constantly evolving America. A series of gun shows become parodies of one another as each salesman shows Theroux the same enthusiasm and willingness to sell him a gun for cash under the table as a “private sale.” Rotting motels along crumbling highways are whipped into shape by Indian immigrants, mostly from Gujarati and mostly with the surname Patel. Big issues like the Ku Klux Klan, desegregation, and the racist treatment of black farmers by lending banks are given both historical context and present-day illumination through conversations with people in churches, cafes and gas stations. Theroux’s greatest skill is that he talks to people—all sorts of them—and he makes them seem interesting even if what they say is utterly unremarkable. Theroux packs in rhapsodies on the Southern landscape, soul food, music, and literature, pondering the South’s idiosyncrasies as he makes pleasant drives along the interstates.

Deep South didn’t need to be a memoiristic personal journey for Theroux. But unlike his previous works about far-flung places—Mongolia, Argentina, Papua New Guinea—Deep South is about America, and despite his years of self-imposed exile and wandering, Theroux is an American. He may not feel himself to be personally complicit in the South’s problems, but his societal position means that he has benefitted from much that has left those he writes about deprived. He is part of the problem, and Deep South suffers from his refusal to acknowledge this fact. Theroux might object to travelogues that explore only the traveler, but it’s time he learned something from them.