Two and a half hours before the pope arrived at Camden Yards on October 8, I stood in a long line debating untheologically whether to return from the experience with a papal keychain, a papal water bottle or just a plain old papal lapel pin. A woman behind me remarked that there were no religious artifacts for sale, which was surprising, since Catholics have perfected mass-market iconography. No glow-in-the-dark rosaries, no sticky-bottomed statues of Mary, no garish holy candles with saints beckoning in technicolor ecstasy. I was disappointed: religious kitsch is kitsch, but often it's evidence of life, of believing energy. Here, the souvenir stand was an agnostic plastic wasteland. Tinker with the logos a little, and this could have been a Michael Bolton concert.

I made my way up to my seat high above first base, my water bottle in hand, and waited. The pope hadn't even left Newark, but the stadium was almost full. I felt sorry for anyone wanting to use the hours before Mass to read (I had a handy pocket copy of Lives of the Saints), to pray or to catch up on some sleep. The pre-game show made rest or tranquillity impossible. It was the sort of spectacle that I had previously associated only with big-time college football. Circles of dancers in different national costumes waved and undulated on the field. The jumbotron monitor on the scoreboard flashed the nonsensical words of a soft-pop religious song: "Shine oh people, Shine our God together." (Give me Michael Bolton. Almost.) And the inanity of the lyrics wasn't nearly as bad as the inanity of the chipper chatter by the on-the-field narrators. One of them asked for a "papal wave," and the spirit instantly and serially moved the arms of this American congregation. A pert usher climbed vigorously up the stadium steps asking if everyone had a pennant to wave. (At what? The Host?) As an army of priests and bishops entered the field, children swayed in time to a synthesizer medley that began with "Amazing Grace," and a second broadcaster noted that "200 of your bishops and 300 of your priests are here today." It was probably a good idea to emphasize the pronoun; I, at least, wished I didn't have to claim this circus as my own. And the TV-style tension started building. "In just moments, our pilgrim of peace will be here ... in Camden Yards," declared one of the ready-for-ESPN baritones. This was the cue for the finale. The dancers retook the field, accompanied by a flip-card brigade and a parade of men and women carrying different national flags. A gospel choir sang, "I want to be ready when Jesus comes." OK, but who could find Him in this pandemonium?

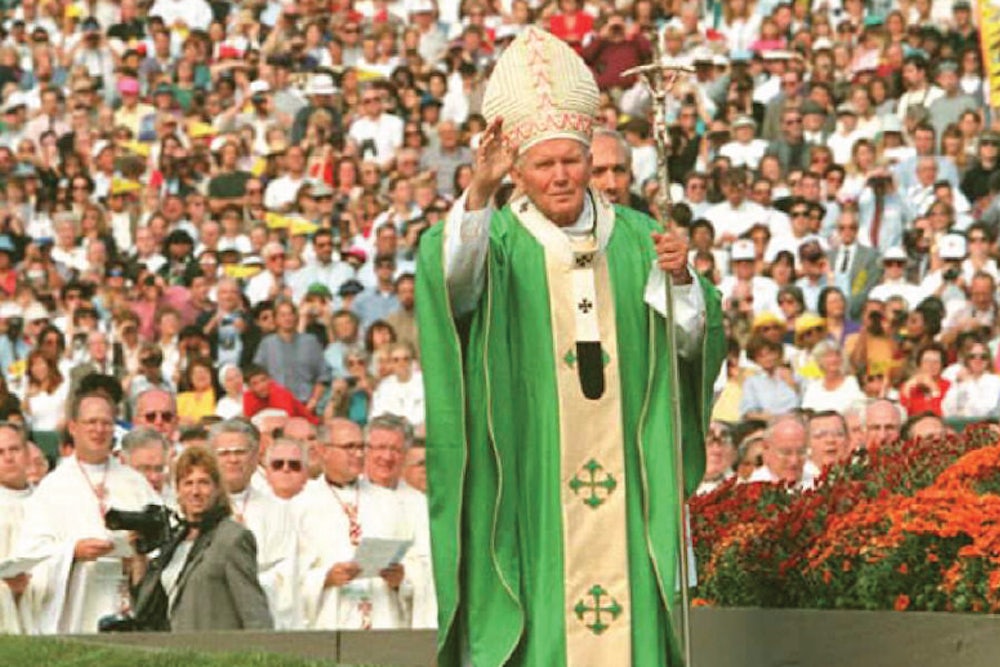

It occurred me to me that this overdone spectacle was perhaps a mischievous plan of the Vatican's, a clever theatrical sermon against American materialism and in favor of Roman sternness. Maybe this was the Holy Father's way of saying he's all that stands between us and Disney: here is what happens when religiosity comes unmoored from a slightly morbid tendency to self-denial; here is what you get, what you deserve, when entertainment usurps godliness. The nadir came when Boyz II Men took the stage and started rapping as the Popemobile entered the stadium. The pope looked a little confused. Who wasn't? Then he emerged from his funny plastic car and walked slowly up to the raised altar in center field, and the unholy carnival evaporated completely. "Peace be with you," he said, and peace there was.

I am a Catholic American who is more American than Catholic, and my views on certain questions have left me unexcited about the pope and the papacy. From my position, popes seem irrelevant or oppressive, or, if they are interesting, wicked and long dead. It would be an exaggeration to say that I was converted at Camden Yards. But I was moved in a way I never expected. I'm not sure how to explain this without lapsing into the schlocky sentimentality that horrified me in the hours before the pope appeared. But John Paul II complicated me. I was present at a real Mass at the baseball stadium. This remote authoritarian figure, who lives in a milieu that I cannot possibly imagine, said a Mass for people like me—no, for me; that's a serious and substantial thing. It was like every Mass I have ever attended—the same cadences, intonations, pauses, prayers—and it was like none. Shivering in Camden Yards' chilly wind, I was caught between the quotidian and the sublime. Now my skepticism will have to share space with awe and, oddly, gratitude.

The most politically troublesome thing about the pope's homily in Baltimore was not his obvious reference to abortion (" ... witnessing to Christ means challenging [the] culture, especially when the truth about the human person is under assault"), but his declaration that "democracy cannot be sustained without a shared commitment to certain moral truths about the human person and human community." American democracy does rest on moral truths, a whole passel of them, but these truths are rarely legislated. You agree that I can treat your absolutes as your opinions, and I agree that you can treat my absolutes as my opinions; and the free pursuit of opinions is more conducive to social peace than the imposition of absolutes. A very catholic country can never be a very Catholic country. And yet Baltimore, where the colonial Catholics who had made religious tolerance the rule were fiercely persecuted when the rules changed, is a fine place to remember that being a Catholic among the catholic is a pretty good fate.

"Faith leads us beyond ourselves," John Paul II said. This is, of course, the antithesis of some varieties of multiculturalism, which suffocate us within our (small) selves. During the Mass I thought about multiculturalism because I couldn't not think about it. In front of me sat a row of girls in unfamiliar uniforms, who identified themselves as Polish Girl Scouts. Not Girl Scouts from Poland—they had mid-Atlantic accents and boxes of Triscuits—but ethnically Polish American girls (and a couple of boys) wearing Polish-language patches and looking wide-eyed when the pope rattled off a proverb in his native tongue. Next to me was an African American woman; on my other side was an Indian family of four who slipped in and out of English. I joined in offering a prayer for "the holy Church of God throughout the world." Then I watched silently and read the jumbotron translations of prayers in French, Swahili, German, Gaelic, Italian, Polish (the girls nodded), Spanish, Tagalog, Korean and Vietnamese. The Catholic Church, divided as it may be, is not a hotbed of ethnic strife. This, I thought, is what American multiculturalism doesn't get. Diversity, when rightly construed, is another name for universality. E Pluribus Unum: those may be the only Latin words many American Catholics understand, but if they really understand them, they understand a lot.