It was during his dime-museum days that Houdini first began to seek professional mediums. In séances attended with his grieving mother, he attempted to contact the spirit of Mayer Samuel, who had once believed communication with the dead was possible. Houdini pawned his dead father’s watch to hire the mediums, but the messages they relayed from the life hereafter were catch-all sentiments. What he heard was spirit twaddle, clearly not the disembodied voice of Mayer Samuel.

The disappointing results, not to mention Houdini’s encounters with spooks on the flimflam circuit, were convincing him that there was no such thing as genuine mediumistic power. He had seen much in his short life, but no marvel that he found unexplainable.

This was twenty years before the ghostly War, when the virtuous Victorians, Lodge and Doyle, imbued the Spiritualist movement with science and fervor. In Houdini’s youth, the séance was stigmatized as an illicit rendezvous in a back parlor. Psychic mediums often advertised their wares in the personals section of the New York Herald, such services being fronts, Houdini suspected, for prostitution, badger games, and other methods of extortion. Just when he began discrediting superstitious practices, though, he met a special girl who felt differently. There was no witch tale she did not believe in.

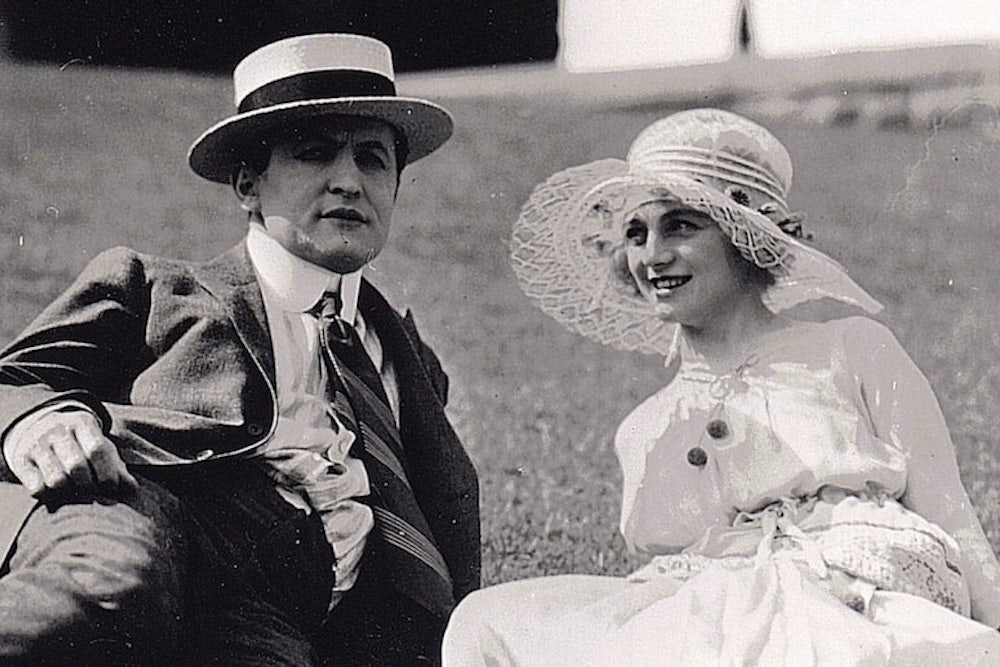

An eighteen-year-old Brooklyn girl of German origin, Bess Rahner was at a music hall when Dash Houdini introduced her to his brother, the senior performer in their magic duo. While just one year older than she, Harry felt the urge to shield her from his rough-and-tumble circles, including brawny Dash, as she was barely ninety pounds and looked like a child when wearing certain outfits. Bess had a lovely, slightly accented voice and large, naïve blue eyes that seemed unaccustomed to navigating the world of grown-ups. She was a seamstress for a tailor shop and a singer with the Floral Sisters. But given that her troupe played the beer halls on the Bowery, her innocent airs may have been more show than substance. Bess would one day joke that she sold her virginity for an orange to a destitute Houdini. Their courtship, such as it was, lasted only a couple of weeks before they exchanged vows and celebrated their matrimony at the carnival resort that was West Brighton.

There was good reason for their elopement. Bess’s people were Roman Catholic, and her mother was horrified to learn that she had wed not just a Jew but a lowly showman. Cecilia Weiss, by contrast, hugged her son’s wide-eyed shiksa bride and murmured that she was now her daughter. Still, it was a shock for Bess to be abruptly removed from her mother and ten siblings. She didn’t really know her new husband; the Weisses’ ways were foreign to her. And becoming Mrs. Houdini meant training to be a part of Harry’s daunting magic act.

Houdini wanted to teach Bess to appear to be psychic, as well as assuage her fear of black magic. One night, he asked her to write the name—that she had never told him—of her dead father on a piece of paper and then burn it in a gas flame he lit. As he directed, she handed him the ashes. When he rubbed them on his thick forearm, her father’s given name of Gebhardt instantly appeared etched on his skin in bloody letters. Bess screamed in horror and fled their tenement. “Silly kid, it was only a trick,” he explained when he caught her outside and calmed her. In time, he taught her the secrets of second sight and prestidigitation; he showed her how to slip into trances like a spirit medium and tell fortunes. He wanted her to replace Dash in the Houdini show, so that they could stage the kind of psychic act that was then the rage on vaudeville.

“Professor Houdini” received the coin from the volunteer in the crowd. Bess on the stage revealed the date inscribed on it. He took the business card from the spectator. She announced the name and address on it. “The wonderful mystical demonstrations of Prof. and Mme. Houdini continue to be a source of wonder to all who witness their marvelous exhibition,” a newsman applauded. As Bess was more agile than Dash, the Houdinis would also develop an electrifying Metamorphosis. Yet they were still small-time. After three years of marriage, the couple had appeared in the Welsh Brothers Circus in Pennsylvania, where Houdini performed as both a magician and the Wild Man of Borneo—a caged beast that crawled around in chains while spectators tossed him cigars and cigarettes to eat, and the ringmaster dangled a slab of raw meat just beyond his reach. For other ensembles or on their own, they had played the parishes of Nova Scotia, the curio stage in dime museums from New York to Chicago, and variety halls in the heart of Dixie. They added a comedy gig to their repertoire, and took a stab at burlesque and melodrama. Nothing seemed to capture the attention of the newspapers or vaudeville managers.

Bess grew despondent and was breaking down physically. When even the dime-museum stints began drying up, Houdini wrote the two great magicians of the Gilded Age, Alexander Herrmann and Harry Kellar, to request work as an assistant. They didn’t need him. He approached four of the major New York newspapers and offered to sell to them, for the mere sum of $20, all of his prized secrets. There were no takers. He attempted to market by mail the special equipment he used for his conjuring routine. There were no orders. He opened a magic school. With the exception of an elderly Chicago businessman, he had no students.

His desperation finally led him to Dr. Hill’s traveling medicine show, the lowest rung of entertainment. Barely able to afford the rail ticket, the Houdinis linked up with Dr. Hill in Kansas, where they performed on the wagon stage and occasionally in small-town opera houses. Between shows the magician sold toiletry articles and miracle elixirs. The Great Houdini had become a piker on the oily circuit. Yet his versatile gifts were not lost on Dr. Hill, who one day proposed something intriguing. With his flowing hair and inspired patter, Hill had the air of a wandering prophet. He wanted a different sort of act on Sundays, something to rouse the goddamn suds on Main Street. He asked if the magician could do a spiritist séance. Smiling confidently, Houdini said that he would raise the dead in every county.

Houdini the great will give Sunday night a spiritual séance in the open light. So read the placards in 1897 when Houdini toured the prairie sticks. His spook show was imitative of the Brothers Davenport— two legendary magicians from his boyhood who seemed able to make instruments play while no living being had hands on them. In Houdini’s replication of the effect, volunteers tied him within a cabinet, where a guitar, a horn, and tambourine were placed upon a table. He should not have been able to free himself to reach these instruments, yet when the light was dimmed a spook recital started. Later, the chamber door blew open, revealing him, still roped and chained, to be the psychic conductor, not the player!

In those days there was a merging of spiritism and stage magic. It was the custom for cabinet test mediums to be cuffed or collared before a dark sitting. Without such restraint a crooked spook might slip into a white robe and waxen mask to fake their apparition, use their foot to raise the séance table, or put the spirit trumpet to their lips and imitate discarnate voices. Mediums were the first escape artists. The Scientific American revealed that it was by no occult force that these miracle workers freed their shackles. In 1897 an exposé called “Spiritualist Ties” explained the means by which crafty psychics slipped their ropes, cuffs, chains, and spirit collars. The report spoke of false bolts, concealed keys, and the slack in any rope tie.

Although Houdini employed such methods, his mental phenomena became his real bread and butter. Occasionally he pretended to put Bess into trance so that the audience might ask questions of the spirits. But most often it was he, the celebrated Psychometric Clairvoyant, who contacted the Other Side. He thought of himself as a psychic detective. When performing in a town he toured its graveyards and took down names of the dead to throw out at his séances. Sometimes he was accompanied in his prowling by a local tipster who filled him in on tragedies and family histories. He combed through health-board records and frequented boardinghouse dining halls in order to cull gossip for his sittings. The dead were active when Houdini visited.

For all that, he began to see that whenever he gave a séance solely by his wits, with no cheating or informant to assist him, his work was still convincing. “No matter what I pulled, someone in the audience was pretty sure to claim it as a direct message...When I noted the deep earnestness with which my utterances were received, and that I was being considered a medium of far more than ordinary psychic powers, I felt that the game had gone far enough.” Mediums had been arrested for doing what he did: taking money under false pretenses. Houdini also realized that despite the easy money, spook shows were a waste of his abilities. He wanted to be a famous showman, not another duper of the gullible.

No spirit would be his savior. Practically as soon as he stopped the necromancy routine, he met the gruff maestro who changed his life. He was back playing the dime museums, this time in Minneapolis, when a Hungarian stranger puffing a Cubana asked him and Bess to coffee after their act. He urged Houdini to abandon the little tricks; they were stock stuff. He pointed out that the magician had two stunts, Metamorphosis and his handcuff act, that no one else could touch. He offered to take him on if he would agree to change his program. And incidentally, he was Martin Beck, proprietor of the Orpheum Circuit, one of the largest chains of vaudeville theaters in the country.

Beck sat back and smiled presciently.

Soon after their meeting, Houdini gave away his prized pigeons and guinea pigs; there would be no more nights of pulling them from a top hat. His card tricks he would never abandon, but gone were many of the accoutrements of stage magic, as well as the mentalist act and the phantoms. The Houdinis had seen the last, they were sure, of Astral Station.

Excerpted from The Witch of Lime Street: Séance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World Copyright © 2015 by David Jaher. Published by Crown Publishers, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.