A theme to which Picasso has returned over and over again is the nature of, and the relationship between, the sexes. Most of the pages of this extended exposition are in a graphic medium, etching, dry point, lithograph, engraving, or some combination of these techniques. They have appeared in large numbers, but sporadically, since about 1905. Seen as isolated works of art, as powerful, or beautiful, or charming, or above all as witty, they are rewarding enough. Now that we have them by the hundreds it becomes apparent that he has been up to the graphic artist's equivalent of writing a novel. Taken as a whole it is inward looking, autobiographical and experimental, and thus it reminds one of the works of Proust and Joyce. It also reminds one of the 16th Century English masque, that wordless entertainment on a classical theme.

Because he is dealing in pictures, rather than in words, each page of this work must stand alone, as well as relate to episodes in the past, and to come. The device which provides continuity is a specific cast of characters. Picasso has created, and remained faithful to, one set. They have developed over the years, and a few have been added, as the exigencies of the medium and. his own growing understanding required. His familiarity with them, together with his incredible facility as a draftsman, explain why he has been able to produce this monumental work, along with other hundreds of drawings, paintings, sculptures and ceramics, unrelated, or only casually related, to its theme.

The character seen most often in these pages is a Beautiful Girl. By occupation she is an artist's model. She is ravishing, a present day Aphrodite. Her hair is long, her eyes in particular are beautiful, set far back in her head. Her face follows the classic model, straight nose, full rounded chin. She is voluptuous, her breasts large, her figure superb. Unlike the classic nudes she is often shown fully and very specifically sexed. Though the years pass she grows no older.

While her occupation does not allow of clothes, she does love to adorn herself with necklaces and belts made of flowers, with jewelry, and particularly with hats. A mirror is her favorite plaything, or she will gaze enraptured at a statue of herself. She plays, occasionally, with a cat or a cupid. Her demands are for attention, and for sex. Otherwise she tends to be unconcerned, passive, and silent. She does have one peccadillo however. Take her to a beach, give her some wine, play her some music, and she will abandon herself to a tremendously seductive dance, in which she displays her charms to the full. She is very feminine. The artist is crazy about her.

She does not know that she is identified, in the artist's mind, with a horse, and with a matador, and this is surely just as well. As a toreador she is charming, as a girl dressed in man's clothing can be. She manages equally well lying nude or semi-nude, in an attitude of abandon, on the back of a bull, or on the Mare which is her symbol and antithesis.

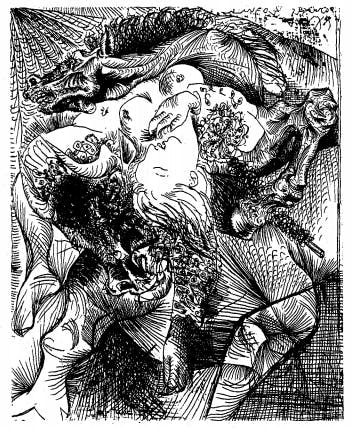

This Mare, a character who appears frequently, reminds one, at certain moments, of the classical horse sacred to Poseidon, symbol of gushing springs. But on the whole she is shown agonized, half starved, brutalized, dying of a puncture in her belly, from which her entrails hang. The enemy of the Mare, the agent of her agony and destruction, is a fearsome Bull, huge, sinister, dark and brutal; the very image of that animal, again sacred to Poseidon, symbol of impetuosity and sexuality. We see the Bull, in several episodes, attacking the Mare, raping her, or annihilating her in scenes of horror, fury and excitement.

The natures of, and the relationship between the Mare and the Bull, so reminiscent of the Corrida, are essential aspects of this work. As it is graphic, the artist can juxtapose, or fuse, animals and people with an ease and celerity impossible in words. Thus the Beautiful Girl becomes the cutest of centauresses, one sees her abstracted with a horse's head, or she wakes to see her horse through a curtained window. Juxtaposition and fusion provide the artist with an enormous vocabulary, and thus allow him to describe the most complicated situations with a minimum of means.

The graphic medium offers yet another opportunity not readily available to the writer. The scenes he depicts can be witnessed by the very people taking part in them, as themselves, in another mood, in another role, or at another age. And indeed a witness, or onlookers, are important parts of many episodes. The most moving witness is a Little Girl. She peers at the scene, or shields her eyes, or looks away, and often holds a light which helps to illumine it. Or she leads the artist, in his role as the blind Minotaur, to safety. There is also a Little Boy, who reminds one very much of his feminine counterpart. These two characters seem to represent the artist or the Beautiful Girl, interchangeably, as they were when children, or as they are forced by circumstances back into a childish frame of mind.

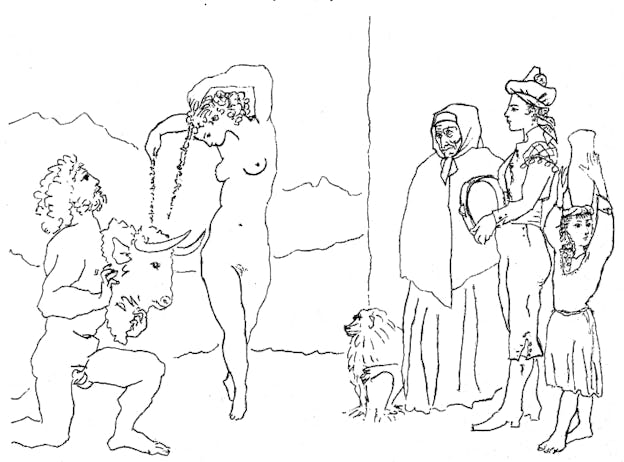

The onlookers include an Old Lady, in a characteristic peasant costume. She is a firm, impassive, experienced, duenna-like sort of person. Still others are two replicas of the Beautiful Girl. In still other pictures the witnesses are simply indicated by eyes. Then there are several pedantic art lovers, silly people who are apt, while the Beautiful Girl lies in the most fetching pose, to myopically examine a picture, paying her no attention whatever.

The environment in which most of the story unfolds is like a classical dream of warmth, all enveloping light, beaches, the sea, with mountains seen across it. Windows are mere holes in the wall, through which one glimpses gardens. The interiors, as one might expect, are often an artist's studio.

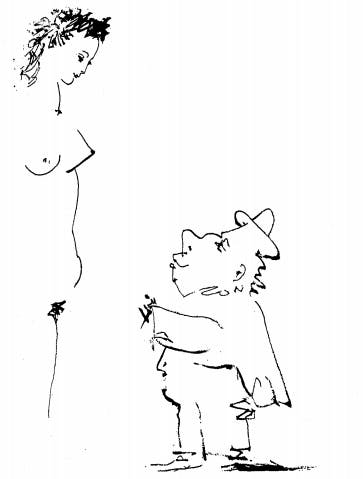

The principal group of characters are people who represent some aspect of the artist himself. At his most inconsequential he appears as a Monkey. We see him painting the Beautiful Girl, or held in her arms, or watching her mating rites. In the same mood he appears as the Little Man. This character is short, clothed, snubnosed, and ridiculous. He stands staring at the Beautiful Girl, transfixed by her femininity, and powerless to do anything about it. He also appears as a Clown. While the Beautiful Girl bids for his attention in the most exhibitionistic possible fashion, the Clown plays with a dog, or makes himself up in a mirror, conscious, but refusing to look. Next in order the artist appears as the Painter. As such he is an old man, clothed, with a scraggly beard, who usually wears glasses but who sometimes has forgotten to put them on. He peers myopically at his easel, or at some one of the Beautiful Girl's charms, intent on his painting, while she poses, serene, passive and unsatisfied. The Painter is not unlike one of the silly Art Lovers, and one of them may stand behind him, as oblivious as he is to the charmer just beyond the easel, the two of them reminding one very much of the Monkey.

It is only in his role as the Sculptor that the artist becomes fully sensate, fully human. In it he reaches his highest potential. Otherwise he is either inadequate to the Beautiful Girl, or made animal by her. He, also, is cast in a classic mold, handsome, straightnosed, with curly hair and beard, nude and well-built. His looks, his environment and his preoccupations again remind one of Poseidon. His eyes are his extraordinary feature - he sees - his eyes are the very model of an artist's, as are those of Picasso himself. The Sculptor makes love with the Beautiful Girl. We see them more than once in the transports of the sexual act.

But the Sculptor cannot really fix his attention on his paramour except as he transforms her into an inanimate work of art. We see them, often, reclining, the Beautiful Girl nestled and passive in his arms, his eyes fixed on a bust he has made of her, his whole attention riveted on it. She too looks at the bust, as in a mirror. Her passivity, her love of herself, here stand her in good stead. Or, once, we see her in revolt. She has knocked over the bust, in this case a self-portrait by the Sculptor, and has propped her mirror up against it. If looks could maim, she would be in a bad way. Or again, he leaves her, not too unhappily, alone with her bust. Or he banishes her. While he admires his likeness of her, she peers in at him through a window.

The Sculptor also appears as a witness, or onlooker, in the form of a bust on a marble pedestal. In this guise he observes the Beautiful Girl at play, or making passionate love to the Minotaur, or admiring her statue.

The author of all this also appears as the Man, a declassicized version of the Sculptor, muscular, homely, very hairy, amply and specifically sexed. The Man is a tough guy, a drinker, a womanizer, in short a very ordinary person. But he has fun.

As the Minotaur the artist appears as a still more potent character. As half bull he attacks the Mare. As half man he attacks the Beautiful Girl. He too is a womanizer, drinker, party goer, and is the catalyst, one feels, who transforms the Sculptor into the Man. But he by no means reaches the full power of the Bull. Like his classical counterpart, the product of a union between Pasiphae and a bull, induced by Poseidon, he is not invincible. One feels that he would like to rape the Beautiful Girl in real earnest, but that she forestalls this by her willingness and her desire. When they are not caught in the act, one sees her diving for his genitals, in a transport of passion, while he defends himself. At disreputable drinking parties she drapes herself across him, abandoned, satisfied and at home. Or she waits while he does his silly drinking. Or she watches over him while he sleeps. She just loves her li'l old Minotaur. When he is killed, by a feminine young man (Theseus, surely) the Beautiful Girl and the Man watch in consternation, while a horrified woman in the audience reaches out to touch him as he dies.

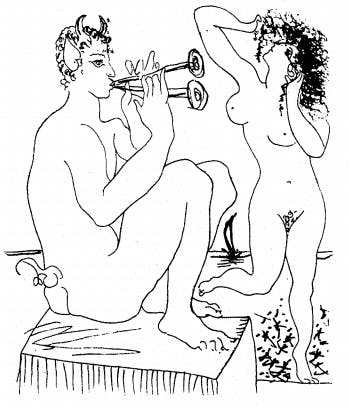

The final staple character, often called Pan, or, A Faun, in the titles, might better be described as Young Rabbit Ears. He is a callow youth, with big ears and Small horns, often very silly because they turn in, or are one behind the other. He has a small tail, and is usually drawn as not much of a man. He plays, always, .a pair of pipes. And it is this Young Rabbit Ears, who. Seated on a block at the edge of the sea, gets the Beautiful Girl to dancing her craziest. Sometimes they are shown alone together, in which case all she will get for her tremendous display is, one feels, exercise.

One of the funniest of juxtapositions in this saga is that in which the Man plays Young Rabbit Ears' pipes, while the Beautiful Girl stands in front of him, disgusted. She says nothing. But one feels that she is thinking "Oh Lord, how long is this foolish business going to take?" The pages of this work can be roughly divided into four categories. There are dozens of character studies of the Bull, the Mare, the Beautiful Girl, and Young Rabbit Ears. There are also numerous studies of the relationship between two characters - of the Bull attacking the Mare, of the Sculptor loving the Beautiful Girl, or excluding her, or of the Minotaur "attacking" (sic) her. The third category deals with more complex situations, in which several characters appear, or in which sculptures and masks play a part. Finally there are the great, the climactic, moments. Two of these, "Minotauromachy" (1935) and "Guernica" (1937) use the familiar characters to present scenes of horror and great distress. Others as the "Dance of the Banderillos" (Feb. 14,1954) are utterly delightful. Here we see the Sculptor, kneeling, holding a mask of the Bull slightly below his face, while the Beautiful Girl dances, playfully pricking the mask with two flowered Banderillos. The Monkey looks on, as does the Old Lady. The Beautiful Girl is also one of the audience, dressed as a toreador and playing a tambourine. The Little Girl is by her side, holding a tall pot on her head. She looks away, distracted by something, for she is not really interested in, or perhaps is repelled by, these goings on.

Another climactic moment is "Two Men with Minotaur and Sculptured Bird" (1934). Here, despite the title, the Beautiful Girl wears a mask of the Sculptor as an old man. The Minotaur, also grown old, watches her. The old Sculptor toasts the sculptured bird, a bird with vestigial breasts.

The interpretation of this monumental work becomes more and more uncertain and diffuse as one ascends from character study to climactic moment. The numerous studies of individuals can be enjoyed simply for their merits and message. The relationships between characters present more difficult problems. The fact that the Sculptor loves the Beautiful Girl is pat. The fact that the Bull rapes the Mare with a sword-like penis, which punctures her stomach, gives one pause. But one cannot afford to ignore this relationship if one is to understand the third category. Thus the inner meaning of, for example, "Bull, Horse and Woman" (June 20,1934) is clear. The picture is intended to contrast the beauty of the Beautiful Girl in intercourse, with the frightful image of the Bull and the Mare in the same situation.

A variation on this theme is given us in "Sculptor's Repose" (March 31,1933). Here the Beautiful Girl lies nestled in the Sculptor's lap, looking away, while he stares, like a visionary, at a sculpture of the Bull raping the Mare. One does not, in this case, witness the rape, rather one understands it by means of the sculpture, as a product of the Sculptor's mind. Whether this rape is an unconscious throwback, representing Daddy Ruiz and Mommy Picasso, or a free association on the Poseidon myth, or a combination of the two, does not really matter. It is a superb device. Without it Picasso would have been greatly impeded by his graphic medium.

The theme reaches its climax in "Minotauromachy." Here we see a woman dressed as a toreador, but bare breasted, lying on the back of the ravaged Mare, holding out a sword to the Minotaur, who takes it in his left hand. With his right he shields this action from the Little Girl and her light. The Sculptor climbs a ladder to the second floor of a building, where two versions of the Beautiful Girl sit in a window watching a dove on the sill. The Sculptor seems to be escaping from the horrible image of the sex act he had conjured up as a child. The fact that this image is the most terrible thing Picasso knows is borne out by "Guernica." Here the Mare, the Bull, the Little Girl with her light, and the Beautiful Girl are used for political purposes, to convey the sufferings of a bombed and ravaged town. Political and sexual imagery become confounded.

The climactic moments transcend the symbolism of the lesser. They must be interpreted on the basis of the lesser, in that it is from all that goes before that they come. They may also be interpreted abstractly. The characters may be seen as ideas, as forces, as states of being. Thus we have Freudian, Jungian, and Amateur interpretations, and it is pleasurable to be able to agree with all of them.

However one wishes to interpret the climaxes, the great body of the work is intuitive, expositive and beautiful. It contains dozens of comments upon and jokes about the relationship of its author to women. Because he is a man of many parts, but nevertheless a man among others, we can all see ourselves mirrored in some of his pages; artists must surely see themselves more often than not, while a few, we can only hope, mirror Pablo Ruiz Picasso alone.