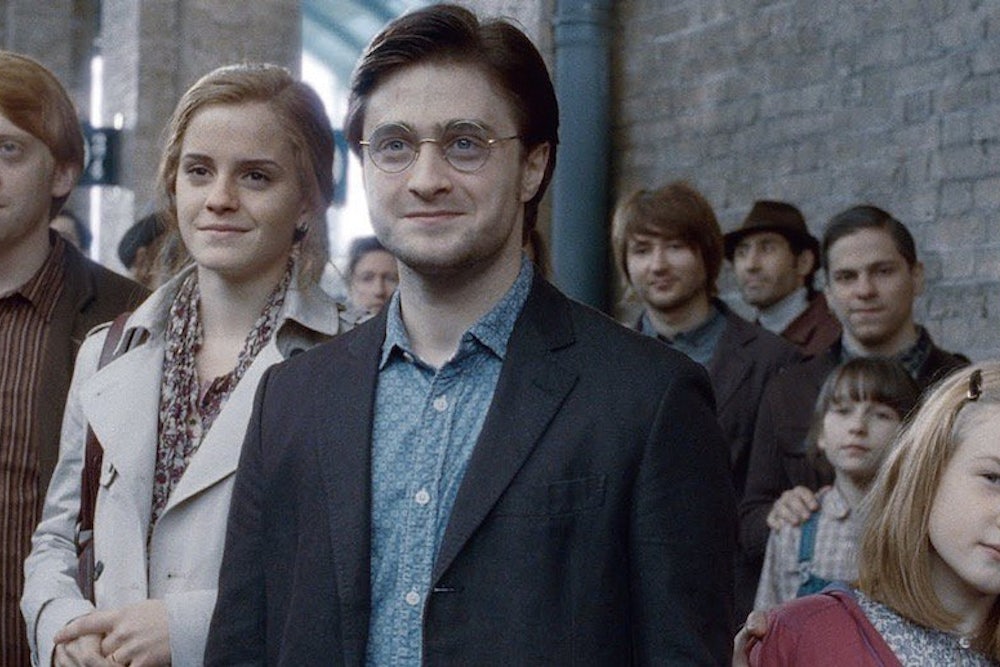

Harry Potter is back and he is your dad: he’s overworked, underappreciated, and he just won’t shut up about his Quidditch days. Earlier today, J.K. Rowling’s Pottermore site announced the “eighth Potter story,” Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. A play in two parts, The Cursed Child will feature a dejected, middle-aged, probably cuckolded Harry Potter and his son, Albus Severus, who has to live up to the metaphoric and literal weight of his name. Here’s Rowling’s summary of the plot:

It was always difficult being Harry Potter and it isn’t much easier now that he is an overworked employee of the Ministry of Magic, a husband and father of three school-age children. While Harry grapples with a past that refuses to stay where it belongs, his youngest son Albus must struggle with the weight of a family legacy he never wanted. As past and present fuse ominously, both father and son learn the uncomfortable truth: sometimes, darkness comes from unexpected places.

This seems in keeping with the later installments of the Harry Potter franchise, which traded silly ghost parties and boarding school hijinks for ennui and lots of whining about how hard it is to kill Voldemort and snog the girl you like. The “cursed child” of the title appears to be Albus Severus, which means that, unfortunately, this is probably not going to be a play about Harry and his boy going back in time to kill baby Voldemort. (This gritty reboot, or whatever you want to call it, is still far more interesting than anything in Deathly Hallows' trite epilogue, "19 Years Later.")

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child opens in July in London’s West End; tickets go on sale on October 30. To the credit of Rowling and her co-conspirators, the play’s previews, which run from June 7–July 29 next year, have a number of reduced ticket options, ranging from £10–£100. How many of those tickets will remain in the hands of the people who buy them is up for some debate, however—I suspect that many will find their way to ticket resale vendors and wealthier theatergoers. It’s hard to think of a play that compares to this one in terms of demand—so long as it isn’t a Spiderman: Turn off the Dark or Spiderman Too: 2 Many Spidermen type disaster, it is going to make bank. And it is going to make twice as much bank because, like the film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows before it, it will be split in two. According to Rowling, this is due to the “epic nature” of the production—that may very well be true, but it also has the effect of dramatically increasing the revenue the play is expected to generate.

This fact that succesful plays generate enormous amounts of money—Rowling won't be charging £10 for long and remember, Cats was on Broadway for 19 years—is one answer to the question of “Why a play?” Another is that Rowling has shown an interest, via the Pottermore platform, in diversifying the Potter brand. Pottermore, which underwent an extensive relaunch this summer, is a fascinating experiment in continued storytelling (though not, as some argue, in the future of the book), but it’s also limited. Most of its content still feels more like DVD extras—bonus material, in other words—than standalone storytelling. The Cursed Child and the upcoming film adaptation of the DVD extra-ish book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them both promise to be more expansive.

The Cursed Child was written not by Rowling, but by the playwright Jack Thorne—though Rowling did provide the story, which she worked on with Thorne and the play’s director, John Tiffany. This may just be because Rowling isn’t a playwright, but it’s nevertheless notable that the official “eighth Potter story” is emerging from the pen of another writer. It also shows a willingness on her part to relinquish some control over Harry Potter and turn it into a more traditional franchise. (The upcoming film adaptation of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, which dramatically expands the narrative of Rowling’s source material, is a useful analogue.) This way, Rowling can retain influence and expand the brand—writing on Pottermore and working with writers and directors on separate projects—while working on other books, like the non-magical thrillers she writes under the name Robert Galbraith. By releasing the first official Potter story by another writer as a play, and not a film or book, Rowling lowers the stakes and the risk—she can dip her toe into uncharted waters while also making what promises to be a substantial sum of money. Seven years after the publication of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Harry Potter may be aging, but the Potter brand is spry.