The story of how George and Barbara Bush set out to make their fortune in west Texas has almost passed into American political folklore. It hasn't quite got the quaint charm of a Horatio Alger story; the future president got his first job in an oil firm run by one of his father's Yale classmates (and a fellow member of Skull and Bones), and when George decided to set up his own company in 1950, the several thousand dollars in seed money was raised by his uncle Herbie Walker, a Wall Street financier. Still, the Bush story has a few elements of the American Dream. Bush worked hard and followed his work wherever it took him, moving his family from Connecticut to Texas to California and back to Texas. He entered a risky business and prevailed through innovation; his company was among the pioneers in offshore drilling. Bush was no empire builder—he sold his business in 1966 for $1.1 million, probably less than it was worth—but he was an honest, industrious entrepreneur, and his business career sufficed for purposes of making campaign commercials.

George Bush's five children are now at roughly the ages at which their parents were struggling to put together the deals that would take them from the dust bowl of the Permian Basin to the manicured lawns of River Oaks. But the paths to fame and fortune chosen by some of the younger Bushes are less inspiring than the one taken by their old man. If the time ever comes to make their campaign commercials—two of the sons are being talked about for high political office—the creative challenge may be a bit greater than in their father's case. Although the Bush boys, like their father before them, have tried to make more money, they haven't always succeeded. Moreover, they don't seem to share his commitment to making money the old-fashioned way. Among the traits that crop up in their financial histories are an attraction to get-rich-quick schemes (including the kinds of get-rich-quick schemes that don't get you rich), and a preference for modern yuppie paper-shuffling over red-blooded, driving entrepreneurship. These are assuredly children of the postwar generation, and not of the era when even men Bred for Destiny, like George Bush, believed that hard work played an essential part in establishing credentials for leadership.

The president's eldest son, George Walker Bush (known as George Jr.), has followed most closely in his father's footsteps. After earning his MBA at Harvard Business School (one ticket George Sr. never punched), George Jr. trundled off to Midland, Texas, where his father had lived, to make his fortune. And like his father, George Jr. took up oil drilling as his principal business. But there the similarity ends. Whereas George Sr. had seen drilling as a way to recover oil, George Jr. seems to have seen it partly as a way to sell tax shelters. During the great energy crisis of the late 1970s and early '80s, George Jr. took advantage of the financial gimmicks of the time to attract investors. One of his specialties was selling limited partnerships in his drilling ventures, partnerships which—in good times—generated profits and which—in good times or bad—generated tax write-offs (although a prospectus for potential investors gave the perfunctory warning that "if an Internal Revenue Service audit of a partnership occurs, there is no assurance that certain deductions allocated to the limited partners will not be challenged").

George Jr. also made a brief excursion into precious metals, joining the board of a company called the Lucky Chance Mine, of which a Harvard Business School classmate and old drilling partner was president. Once a hot number on the "penny stock" charts, which are at the K-Mart end of the over-the-counter market, Lucky Chance proposed to revive a long-defunct California mine that dated back to the days of the great Mother Lode at the beginning of the 20th century. The idea was to capitalize on the sharp rise in gold prices of the early '80s. Unfortunately, the plan faced at least two obstacles. First, the mine was flooded. (The mining company says it has been trying to drain it for the last several years.) Second, the company couldn't be 100 percent sure that somebody else didn't have a legal claim to the gold. As an annual report admitted, the question of who owns any gold found in the mine is "subject to many uncertainties of existing law and its application." It's not surprising, then, that after Bush joined the company, its stock went in only one direction: down. The stock's peak the year before his arrival was $1.62 a share. Last year it traded at between two and six cents per share. Bush eventually gave up his place on the board of the company.

In 1984 George Jr. merged Bush Exploration with another venture called Spectrum 7 Energy Corporation. When the solidarity of the OPEC cartel evaporated and world oil prices collapsed, George Jr.'s oil ventures did not fare well. By 1986, when oil prices dropped 50 percent in six months, the pool of new capital for his drilling projects was as dry as the west Texas desert. Around this time, during one of his less optimistic moments, George Jr. lamented to the New York Times that "I'm all name and no money."

Not for long. George Jr. managed to attract a white knight, a high-flying company called Harken Energy, which collects failing companies and tries to turn them around. Before he even had to turn his business school textbook to Chapter XI, Harken stepped in with a merger deal. George Jr. got no cash or role in Harken's management, but he did get 1.5 million shares of Harken restricted stock, warrants to buy 200,000 more, and a seat on Harken's board.

If George Jr. has found shelter from the storms that have shaken his father's old industry, his younger brother Neil has had harder luck. Neil, who works out of Denver, started an oil firm, called JNB, with two friends in 1983. The results of his first exploration projects were less than boffo: out of 16 holes drilled, 15 were dry. Bush told the Times his company was more vulnerable than others because he didn't set it up until after oil prices had begun to crash. Indeed, that would be a disadvantage.

Lately Neil has had something in common with his father: both are trying to cope with the fallout of the savings and loan crisis, though in very different ways. Until his resignation during the election campaign last summer, Neil was a director of the Silverado Banking, Savings and Loan Association, the third-largest thrift in Colorado. Weeks after the resignation, regulators stepped in and seized control of Silverado, which had gone broke. The Federal Home Loan Bank Board said Silverado's failure was the result of "alleged violations of laws, rules, and regulations and unsafe and unsound banking practices." Investigators indicated they were particiularly interested in a series of unusual transactions in which Silverado loaned money to property developers who then agreed to buy the S&L's stock. This allowed Silverado to boost its capital, but critics charge it also created a misleading picture of the bank's net worth. And the financing scheme does seem to have a certain circular quality to it.

The banking industry trade press reported that it could cost the government $1 billion to rescue Silverado, one of the most costly single-bank bailouts of the entire S&L crisis. Neil Bush received a subpoena to testify in a lawsuit brought by angry homeowners in suburban Denver who lost money when a housing project financed by Silverado collapsed. They "have a concern about the role [Bush] played as a director," according to their lawyer. Bush's lawyer calls the subpoena "harassment."

The most political of the new generation of Bush entrepreneurs is perhaps Jeb Bush, 35. Unlike Neil and George Jr., who emulated their father by striking out to make their fortunes in the West, Jeb headed south. With his Hispanic wife in tow (she's the mother of the "little brown ones") Jeb settled in Miami, immersing himself in such local pursuits as the real estate business, charities, and the local Republican Party. Jeb served for three years as Dade Gounty Republican chairman, and later was appointed Florida's secretary of commerce. In Miami, Republican politics has come to intersect with the byzantine world of Latin American exile politics. Jeb bas been involved with some of the exile community's popular anti-communist crusades, such as Radio Marti and the Nicaraguan contras. He became so deeply committed to these causes that Insight magazine, the Moonies' answer to Time, recently suggested that Jeb "eventually may become a shadow assistant secretary of state for Latin America."

In addition to its reputation for feverish politics, southern Florida has long been known as a refuge for businessmen whose ethics are, one might say, less than immaculate. Jeb Bush has not entirely avoided contact with such individuals. His name cropped up two years ago in an investigation by a House Government Operations subcommittee into the affairs of International Medical Centers, once America's largest health maintenance organization. International Medical fell on bad times when its president, a flamboyant businessman named Miguel Recarey Jr., was indicted on racketeering charges and fled the country. The company's contract with the Medicare program, which had provided much of its business, was cancelled.

In congressional testimony, Mac Haddow, a former aide to Reagan administration Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler, alleged that in 1984, while Jeb Bush was Dade Gounty Republican boss (and, of course, the vice president's son), Jeb contacted Heckler on International Medical's behalf. According to Haddow, who himself was later sent to prison on unrelated corruption charges, Jeb lobbied Heckler for a special favor that would allow the firm to take on more Medicare patients than government regulations normally allow. Haddow claimed that Jeb also phoned Heckler to vouch for the good character of International Medical's officers, although he didn't recall whether Jeb bad specifically vouched for Recarey's bona fides. (International Medical also hired as a lobbyist former White House aide Lyn Nofziger, later convicted in the Wedtech scandal.)

At the time of the House investigation, Jeb Bush said he couldn't remember talking to Heckler, but that he had spoken about International Medical to another high-ranking Health and Human Services Department official. Bush also said he knew Recarey as a Republican Party contributor. The Miami Herald added to the intrigue, however, when it uncovered another link between the two men. It reported that Jeb's small real estate firm had received $75,000 in fees from Recarey after Jeb had made his phone calls to Washington. In an interview with Newsday last year, Jeb denied that the fees were related to any lobbying he did on Recarey's behalf, but he conceded that his company had failed in the task it was supposed to perform for the $75,000: to find a new corporate headquarters for International Medical. (Jeb was said to be overseas when I called his office for comment.)

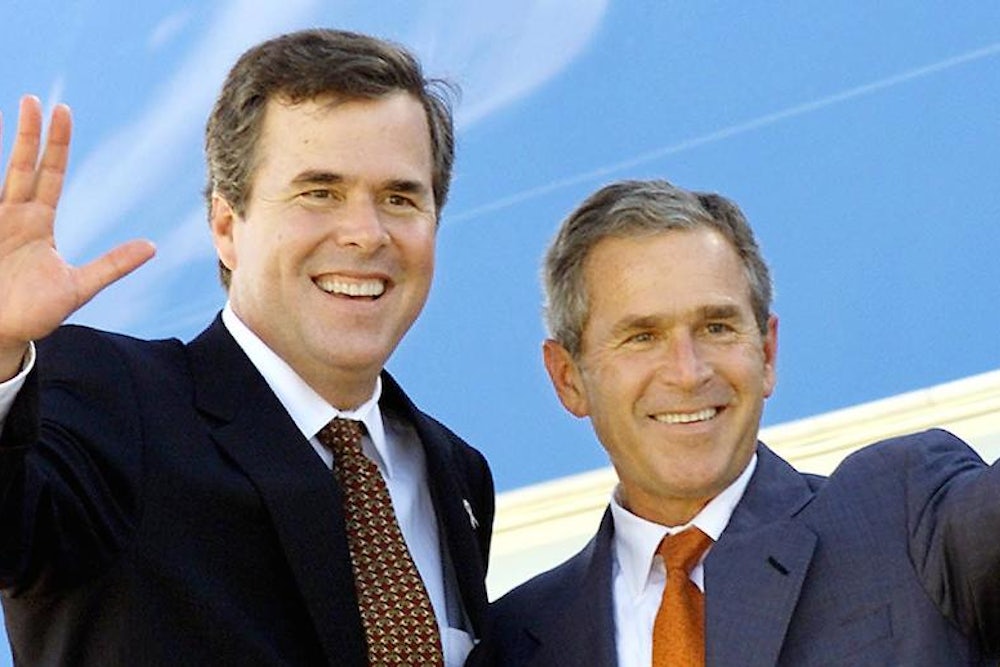

Despite their spotty track records as businessmen, the young Bushes are already being touted as potential stars in a family political dynasty. Jeb has been mentioned as a possible challenger to two Florida Democratic congressmen, Dante Fascell and Claude Pepper, and there has also been talk of his running for lieutenant governor if his friend, Florida Governor Bob Martinez, seeks a second term. Jeb has already served as an ambassador of his father's kinder, gentler foreign policy by making a whirlwind tour, with one of his young sons, of earthquake-stricken Armenia.

Meanwhile, George Jr., as he waited out the shakeout in the oil patch under Harken Energy's protective umbrella, became involved heavily in his father's campaign. Lately he is being discussed as a possible Republican candidate for governor of Texas. His political stock didn't rise any, however, when he served as a surrogate for his father in John Treen's unsuccessful campaign against ex-Klansman David Duke for a seat in the Louisiana legislature.